About three years ago, Eduventures Research set out to answer two simple questions: In what ways had schools implemented competency-based education (CBE)? And, what might be its prospects for further growth?

Having tracked its development among a handful of promising initiatives—like Western Governors University (WGU), Southern New Hampshire University, and Capella University—we wanted to more clearly assess whether CBE was poised for more mainstream adoption or would remain a niche innovation. If the logic of CBE is so compelling, why had it failed to scale and achieve significant impact outside of a few, exceptional institutions?

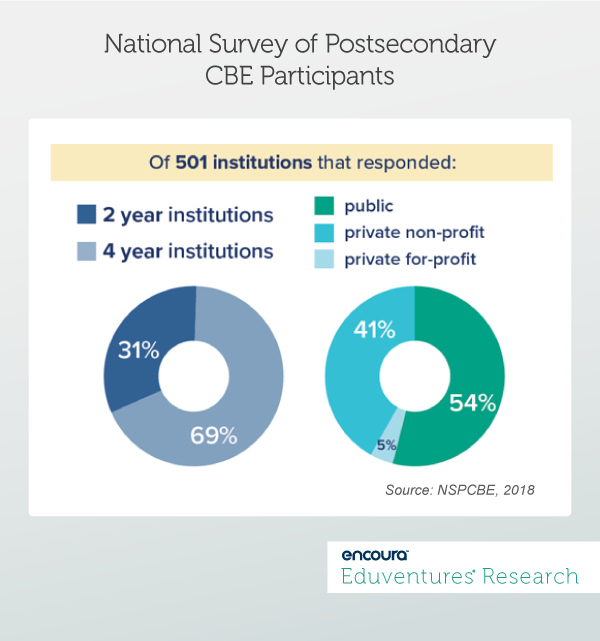

The resulting research series, Deconstructing CBE (editions 2016 and 2017), addressed the size and shape of CBE implementation in higher education. This week, in a new partnership with the American Institutes for Research (AIR) funded by The Lumina Foundation and Ellucian, we will begin releasing the results of a new study, the 2018 National Survey of Postsecondary CBE (NSPCBE). With more than 500 participating institutions from across the U.S., the sample for this study doubles that of our 2016 study. It also represents a healthy cross section of schools, including R-1 institutions, two- and four-year schools, public and private non-profits, and for-profits. The results allow us to look back on how CBE implementation has changed since 2016.

Here’s a sample of what we’ve discovered:

Except for a few giants, CBE implementation remains small.

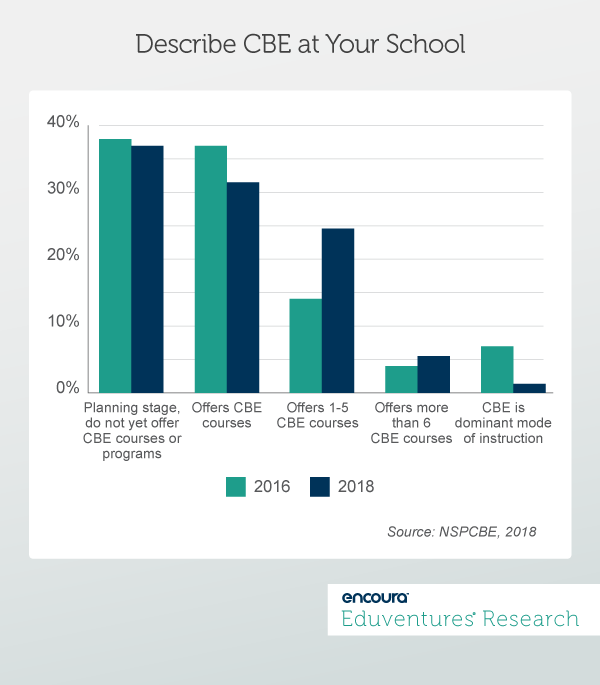

Deconstructing CBE revealed that with the exception of a few schools, most CBE implementation occurred at the program and course level. In 2016, 37% of schools with either CBE in place or in the works reported that they were offering CBE at the course level. Only 7% described CBE as the “dominant mode of instruction” at their schools.

In 2018, this pattern remains essentially unchanged except for some growth among small programs (Figure 2).

CBE is still viewed as a vehicle to expand access to higher education.

Nearly 61% of NSPCBE respondents report that their school has either adopted or is planning to adopt CBE in order to meet the needs of “non-traditional” learners and workforce preparation. These findings are consistent with the results from the 2016 survey: 60% of that sample reported that CBE programs were designed to expand access to higher education for non-traditional students.

CBE is slowed by regulations, start-up costs, and a scarcity of expertise.

When asked about what hinders CBE implementation, schools cited federal student aid regulations, inadequate “business processes,” and program start-up costs as top barriers. For those still exploring CBE, the lack of on-campus expertise was cited as a significant barrier (58%). This finding underscores the value of efforts to identify CBE related best practices whether through ED’s EQUIP program, C-BEN, or the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning (CAEL)

There is no detectable CBE “big chill” effect.

Almost a year ago, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) found that WGU had violated long-standing distance education regulations and could be compelled to return $713 million in federal aid. Eduventures wondered whether this federal action would “chill” interest in further expansion of CBE. This was followed by a delay in the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act (HEA), which had the potential to reenergize interest in CBE. Did interest in CBE erode in light of these developments?

A year later, the OIG finding seems unlikely to be enforced. NSPCBE . Among the more than 500 schools responding, 78% expect that that CBE programming will grow during the next five years. This corresponds to the level of expectations in 2016.

The CBE Paradox

Given these developments, the NSPCBE results arrive at a particularly important moment for higher education CBE. The logic of awarding credentials based on the mastery of competencies rather than seat time has had enduring appeal to many educators. Likewise, Eduventures’ Adult Prospect Survey continues to suggest that adult learners actively seek programs with many of the hallmarks of CBE: flexible pacing, credit for prior learning, and personalization.

The complexities of implementing CBE, however, have not dissipated since 2016, and are unlikely to do so in the coming years. This is the crux of the CBE paradox: in the annals of higher education, CBE could thus far win the prize for the most widely admired but sparsely implemented method of expanding access and improving student achievement.

Efforts to implement CBE may expose as much about the challenges of program innovation as they do about the higher education seed bed where proponents hope it can grow. Perhaps higher education may never be ready for widespread CBE implementation. Is CBE destined to remain an incremental innovation in light of financial aid requirements, outmoded regulations, and a scarcity of expertise? Or is there something intrinsically challenging about how teaching, assessment, and pedagogy function within it?

Later this year, look for a full analysis of the 2018 National Survey of Postsecondary CBE that will explore this data in more depth.

Thursday, September 27

State of the Field: Highlights from the National Survey of Postsecondary CBE

CBE Exchange, Orlando, Florida

Thursday, October 25

Assessing the Results of the 2018 Joint AIR/Eduventures Survey of Higher Ed CBE

WCET annual meeting, Portland, Oregon

Friday, November 27

CBE and Adult Learner Preferences

CAEL annual conference, Cleveland, Ohio

Thank you for subscribing!