This is Part 1 of The College Enrollment Paradox. Read Part 2 here.

This summer marks the longest period of uninterrupted economic growth in U.S. history—a full decade since we exited the Great Recession. Fall 2019 will almost certainly mark another record: a 10-year decline in first-time college enrollment. Such a decline has not happened since federal records began in 1869.

This enrollment downturn has been going on for so long that it has faded into the background, partly because it is muddied by enrollment growth for certain types of schools. But what are the causes of the enrollment downturn? Who are the winners and losers? And, what do today’s trends

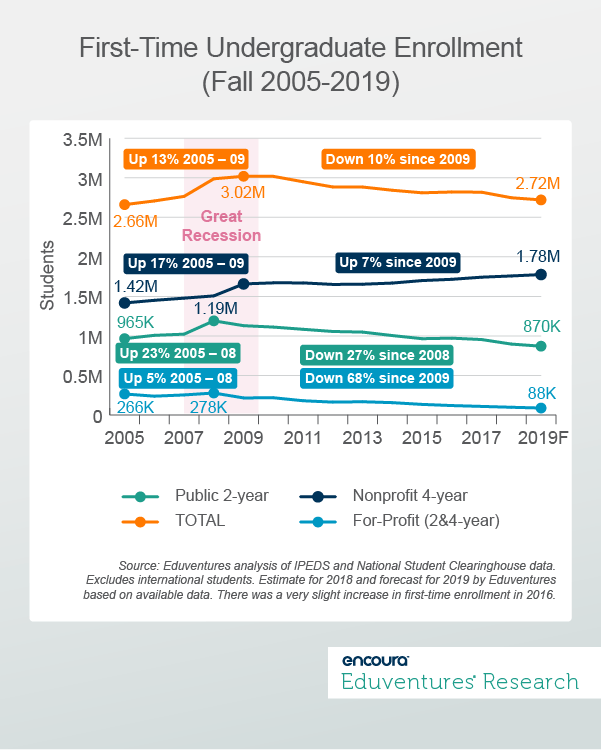

Figure 1 shows first-time undergraduate enrollment from fall 2005 to fall 2019 among public two-year schools, nonprofit four-year schools, and for-profit schools.

To understand the enrollment downturn of the past 10 years, it is crucial to take account of the Great Recession that lasted from December 2007 to June 2009. Enrollment surged during this period, rising 17% at four-year nonprofits and 23% at community colleges.

Then, from 2009, total domestic first-time undergraduate fell 10% over the next decade. The drop was an eye-opening 27% for community colleges—from their peak in 2008—while nonprofit four-year schools, both public and private, ground out a 7% gain.

For-profit schools made some headway during the recession but have since lost 68% of their first-time enrollment. During this time, many for-profit schools were focused on adult learners, most of whom were not first-time students. Of course, for-profits overall have lost a lot of ground in the adult market, too.

Fewer 18 Year Olds?

So, why has overall first-time enrollment been down for so long?

Because most first-time undergraduates fall in a narrow age range, age 17-21, the role of changes in the underlying population is straightforward to track. Also, enrollment at this age is less vulnerable to economic highs and lows. Demand for higher education has generally been up over time, in line with improved high school graduation rates and employment trends that favor a college degree.

So, if demographics are the main driver, the data should show first-time undergraduate enrollment decline in line with a drop in the underlying population, plus upward compensation for improved high school graduation and college-going rates.

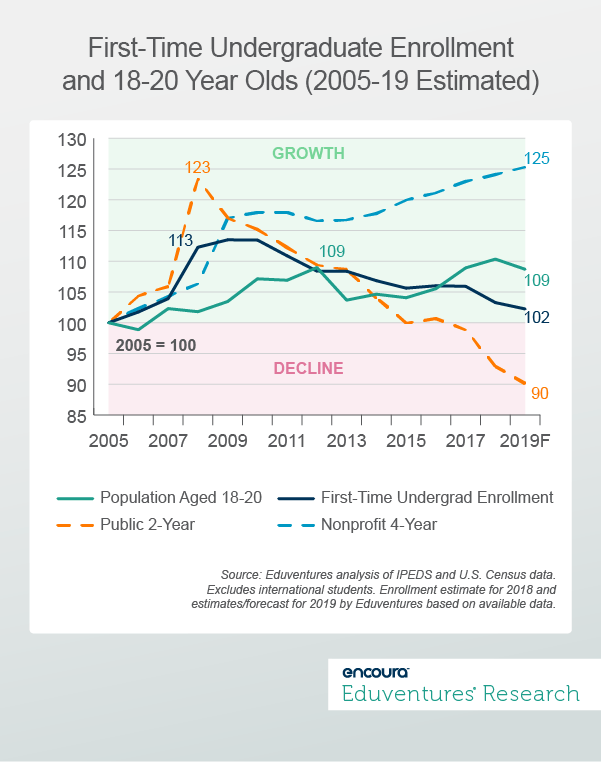

Figure 2 suggests the story is not so simple.

Since 2012, even though the traditional college age population—the green line—has picked up a little in recent years. First-time college enrollment—the navy blue line—has fallen. There is no question that parts of the U.S. are suffering significant population declines at the traditional high school age, but this is offset by growth elsewhere.

Based on Figure 2, from a national perspective, it is hard to blame “fewer 18 year olds” for the fall in first-time enrollment.

Re-Enter the Economy

Ten years of uninterrupted economic growth helps explain why two-year, first-time enrollment declined despite a recent revival in the number of 18-20 year olds. Individuals considering a two-year institution may be more influenced by economic conditions than their four-year peers. The recession-induced 2008 spike and then rapid decline in community college enrollment shown in Figure 2, underlines the point.

It is also clear from Figure 2 that, in aggregate, nonprofit four-year schools appear to have shrugged off any demographic or economic headwinds. After a period of consolidation after the Great Recession, four-year nonprofits have continued to expand first-time enrollment. The nonprofit four-year boom has been insufficient to wipe out the marked decline among two-year schools, or the weakness in the (smaller) for-profit sector, but more 18-20 year olds are enrolled in nonprofit four-year schools than ever before.

And, four-year first-time enrollment growth far exceeds growth in the underlying 18-20 year old population. High school completion rates that continued to edge up over the period certainly helped but cannot fully explain the four-year enrollment growth.

The recession-induced drop in state appropriations to public colleges and universities is another factor. Many four-year schools have used their brands to bump up enrollment—and raise tuition—while appropriations claw their way back in some states and continue to diminish in others.

Of course, there are winners and losers among today’s four-year nonprofits. Flagship schools are squeezing out many lesser known institutions, and a few four-year schools have shut their doors.

The Bottom Line

The bottom line for two-year schools is that their value proposition is highly, and perhaps excessively, sensitive to economic conditions. In the long-run, prospective two-year students might be better off investing in their education over just taking a near-term job, but community colleges have a communication challenge.

It might be argued that the bottom line for non-profit four-year schools is that overall decline in first-time undergraduate enrollment hides a four-year success story. Frictions around price, aid, and value remain relevant, but 18-20 year olds are betting on (four-year, nonprofit) higher education like never before. College alternatives, such as bootcamps and apprenticeships, are growing but remain relatively insignificant.

Another perspective is more cautious. To sustain enrollment growth or even stability, many four-year schools have had to spend heavily on marketing, relax admission standards, splurge on aid, and strain institutional support structures. From where many community colleges sit, four-year enrollment momentum has been at their expense. Students who might once have enrolled at a two-year school, and perhaps transferred to a university later, are now courted by universities from day one.

But while this trend is good for university balance sheets, do these less traditional students have the preparation and support they need to thrive in a four-year setting? Some four-year schools may face a reckoning in the guise of depressed student retention or increased support expense.

A forthcoming Wake-Up Call will consider how four-year schools are managing their hard-won enrollment gains, and how relations between two- and four-year schools, many part of supposedly harmonious systems, are affected.

A Look Further Out

The impact of the Great Recession is far from over. Normally, birth rates go up in good economic times, and down in bad. Births tumbled during the Great Recession, and have kept falling, despite a decade of economic growth. This means, come 2026 when the first children of the recession reach traditional enrollment age, higher education faces a demographic downturn that will make today’s market seem like a golden age.

But the good thing about demographic trends is that they are easy to predict. The birth rate 18 years ago reveals a lot about the market for traditional age college enrollment. Schools of all types should be wise to this reality long before it hits.

Thursday, August 29, 2019 at 2PM ET/1PM CT

Much has been said about the characteristics and preferences of Gen Z, but new Eduventures research unveils that vast differences exist even within this generation. From distinct search strategies to micro-generational behaviors and attitudes, recruitment outreach needs to be more personalized than ever. Learn which outreach strategies help your marketing team engage the right students at the right time, and understand what many students wish colleges and universities got right.