As the 21st century nears the two-decade mark, more than 90% of degree or certificate granting colleges and universities remain wedded to an idea first introduced alongside the birth of the flush toilet, typesetting, and the curtain rod. We speak, of course, of the oddly persistent credit hour, a.k.a. the Carnegie unit, a 1906 innovation developed by the Carnegie Institution for the Advancement of Teaching in order to design a sustainable pension system for a growing population of college teachers.

This curious state of affairs is just one insight to be derived from Eduventures’ most recent study of competency-based education (CBE), State of the Field, Findings from the 2018 National Survey of Postsecondary CBE (NSPCBE). The NSPCBE reveals that schools seeking to measure academic progress based on the mastery of competencies, rather than the accumulation of credit hours, remain few and far between.

For now, the verdict is in: .

Created in a new collaboration between Eduventures and the American Institutes for Research® (AIR), the NSPCBE represents the largest survey of postsecondary CBE implementation and interest to date. It includes responses from leaders and academic directors at 500 schools with existing CBE programs or with plans to build future programs. For Eduventures, it marks the completion of three years of research into CBE, funded by Ellucian®, for AIR it represents the first of three years of new research, funded by the Lumina™ Foundation.

CBE Today: Small but Optimistic

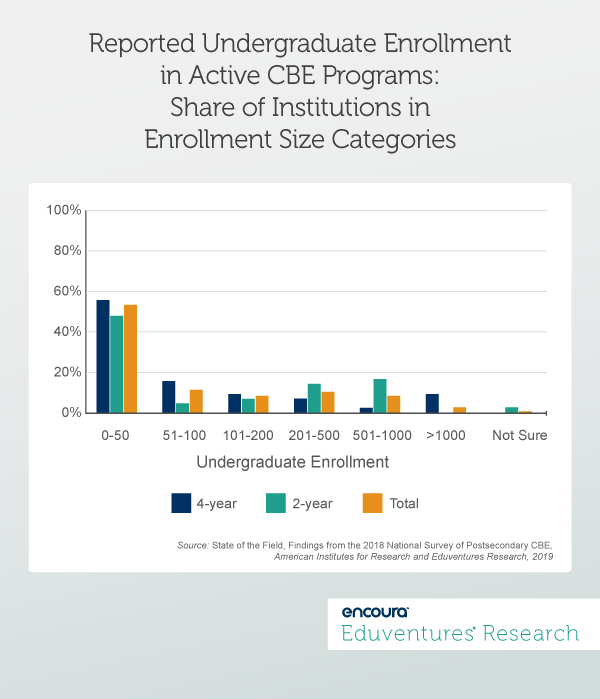

Eduventures and AIR designed the NSPCBE to inform institutional leaders, faculty, and policymakers of how and why CBE is being implemented, and what obstacles await schools hoping to build new programs. Through this lens, CBE emerges as not only a potentially effective innovation for adult and non-traditional learners focused on securing employment, but one that remains on the fringe of mainstream higher education. As the NSPCBE reveals, outside of a few large, well-known CBE-centric schools, most program enrollment remains nascent. We asked institutions with functioning CBE programs to report enrollment. As was the case in Eduventures’ 2016 study, evidence strongly suggests that among two- and four-year schools, most programs enroll fewer than 50 students. Figure 1 shows the percent of institutions by undergraduate enrollment; this pattern was also consistent for graduate enrollment.

What's next for CBE?

Results from the NSPCBE come just as the federal Education Department (ED) embarks on a new round of negotiated rulemaking, commonly known as “neg-reg.” The intent of any neg-reg process is to engage a broad community of stakeholders in an attempt to build consensus around a redefinition of essential policies and procedures. Notably, the initial rounds of neg-reg have included a re-examination of the credit hour and direct assessment, both central to CBE. This has begun as the chances for a timely reauthorization of the Higher Education Act (HEA) have vanished. At the same time, the ED has recently rejected the guidance of its own Inspector General’s office, concluding that CBE giant Western Governors University (WGU) did not violate the regular and substantive interaction requirements of the distance learning regulations. Rather than refund the ED $713 million, as requested by the ED’s Inspector General, WGU will only have to pay back a nominal $2,500, largely due to an administrative error. While this decision was not unexpected, an audible sigh of relief could be heard across WGU’s offices. These are not random occurrences, nor is it inconsequential that CBE remains central to these debates. Despite its marginalization, CBE implementation foreshadows - like a barometer measuring the weather - how higher education policies and practices can adapt to new circumstances and shifting demographics. Within programs large or small, CBE continues to enable schools and policy makers to test out a range of stubborn but valuable questions:- Can program innovation in higher education effectively coexist alongside necessary consumer protection measures?

- Will a redefinition of what some have termed the “inhibitive” credit hour advance student achievement or erode quality?

- Can the “regular and substantive interaction” requirements governing Title IV access be effectively revised to reflect new trends in teaching and learning?

- Motivations for adoption: Institutions see CBE as a way to serve nontraditional students and improve workforce readiness.

- Scope of adoption: Many institutions’ adoption activities fall short of full CBE programming.

- Scale of enrollment: Most CBE programs currently serve relatively small numbers of students.

- Faculty role: Faculty are still fulfilling a broad range of roles in active CBE programs.

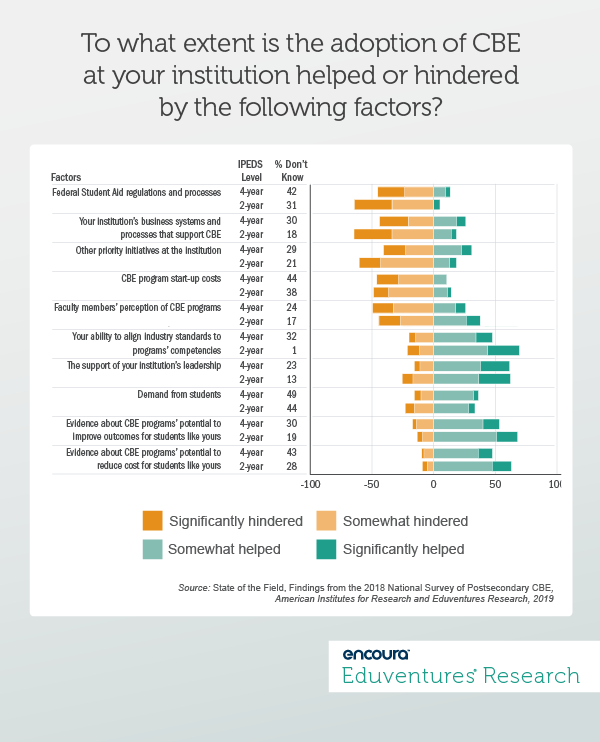

- Barriers to implementation: Perceived barriers to CBE implementation represent both internal and external factors.

- Future of CBE: Most institutions are optimistic about the future of CBE.