It’s that time of year again. As has become an end-of-year tradition at Eduventures, we asked five of our analysts to reflect on a single question: “What did you learn this year?”

Some answers identify truly break-through moments in our understanding of the student market or evidence of significant change in higher education over time. Others, however, provide a sense of déjà vu to findings from a decade ago, or identify new approaches to old problems.

We hope you enjoy reading these posts and reflecting, along with our analysts, on another year of Eduventures research!

Click the author to jump to each section:

Johanna Trovato: Community College Students Have Dreams and… Fail?

Richard Garrett: Online Learning is Still Preferred by the “Wrong” Students

James Wiley: Reflections on the Difficulty of Tracking Technology Trends

Kim Reid: The Evolution and Migration of Students through the Recruitment Cycle

Michael Miller: The Call for Career Readiness Crescendos

Community College Students Have Dreams and… Fail?

By Johanna Trovato

In 2019, I learned that most traditionally-aged community college students do not see their enrollment school as their final academic destination. Most of these students intend to continue their education at a four-year college or university. In fact, according to the Eduventures 2018 Survey of Admitted Students™, 70% of students who enrolled at a community college planned to complete a bachelor’s degree.

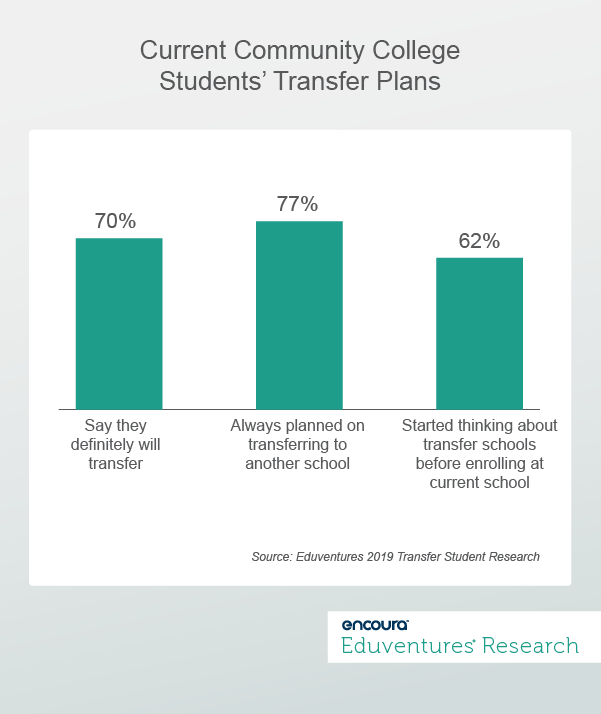

Data from our 2019 Transfer Student Research Report, based on a survey of current undergraduate students who indicated having transfer plans, reveals just how committed these students are. Figure 1 shows that these community college students are highly likely to say they will “definitely transfer," that they “always planned on transferring,” and that they "started thinking about transfer schools before enrolling at current school."

Community college serves as an affordable pathway to students’ dreams of social mobility. Often, these are first-generation students from lower income families. It worries me, however, that according to the National Student Clearinghouse, which tracks the paths of community college students, only 44% of the 2012 cohort that transferred from a community college to a four-year school earned a bachelor’s degree within six years. The completion rate dropped to 37% for lower income students. Despite their optimism and ambitions, many community college students never achieved their goals.

What is causing this? Are these students ill-prepared, do their goals change, or are we setting them up to fail?

As part of our Transfer Student Research, we have also collected data from students who already transferred. Perhaps it will shed some light on these and other questions in 2020.

Online Learning is Still Preferred by the “Wrong” Students

By Richard Garrett

In 2019, I learned more about why completion rates for fully online programs continue to trail those delivered on campus. For context, I have conducted surveys of prospective adult learners for well over a decade. A perennial question is interest in online study. In our latest Eduventures Adult Prospect Survey (2019), one finding emerged – a throwback to 2009: at the undergraduate level, the least committed and least well-resourced prospects exhibit the strongest interest in fully online study.

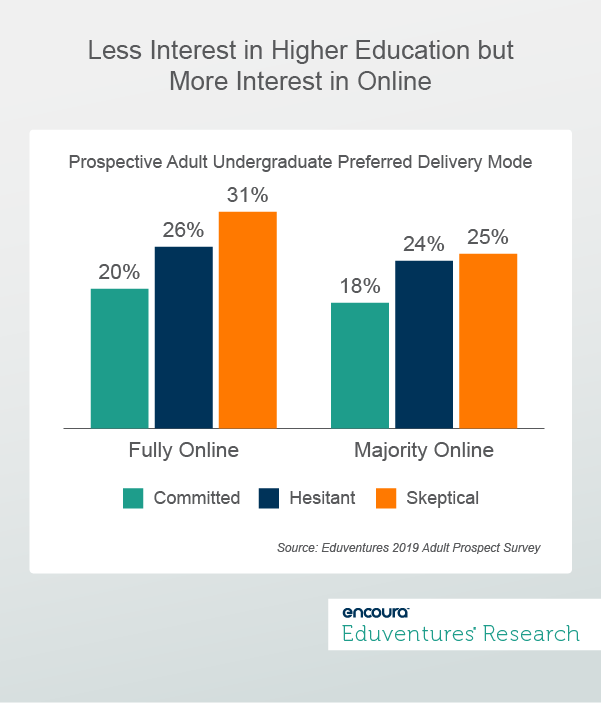

Figure 2 divides adult undergraduate prospects, aged 22 or older, into three groups:

- Committed: those who say they “definitely” or “probably” will enroll in some form of higher education in the next three years;

- Hesitant: those who initially said no to enrollment but expressed strong interest if time or money were no object;

- Skeptical: those who initially said no to enrollment and expressed only limited interest if time or money were no object.

“Skeptical” prospects express the greatest enthusiasm for online and “Committed” prospects, the least.

Why does this matter?

These persistent disparities betray that the online learning brand is still defined by convenience and flexibility. The “worst” undergraduate prospects, those without the motivation or resources to commit to higher education, tend to view online (wrongly) as an “easier” path, while the “best” ones think (wrongly?) that online learning cannot embody everything they want from higher education.

It also matters because, according to our estimates, the “Hesitant” and “Skeptical” groups make up 75% of adult prospects. Our analysis of federal data shows a persistent average completion gap between fully online and other schools, when it comes to non-first time, part-time undergraduates. Do far too many students opt for a delivery mode that is a poor fit?

Online higher education has come a long way since 2009. Many more students are enrolled online, across a much wider array of schools and programs. The delivery mode has opened doors for numerous non-traditional learners, and practitioners continue to look for ways to optimize online for different circumstances.

As we enter a new decade, the looming question is if, how, and when the online brand will evolve. In 2029, will the “best” adult prospects—finally—be most likely to prefer online study?

Reflections on the Difficulty of Tracking Technology Trends

By James Wiley

In 2019, I learned that, when it comes to the Higher Education Technology Landscape (Landscape), one thing is clear: it is difficult to get a good sense of the changes in higher education technology.

Each year, products and functionality appear or disappear, terminology fluctuates, and vendor marketing emphasizes different aspects of their products. As a result, it is challenging to determine trends in the overall world of higher education technology, which creates hurdles for stakeholders who would like to read these trends as proxies for what concerns institutions most.

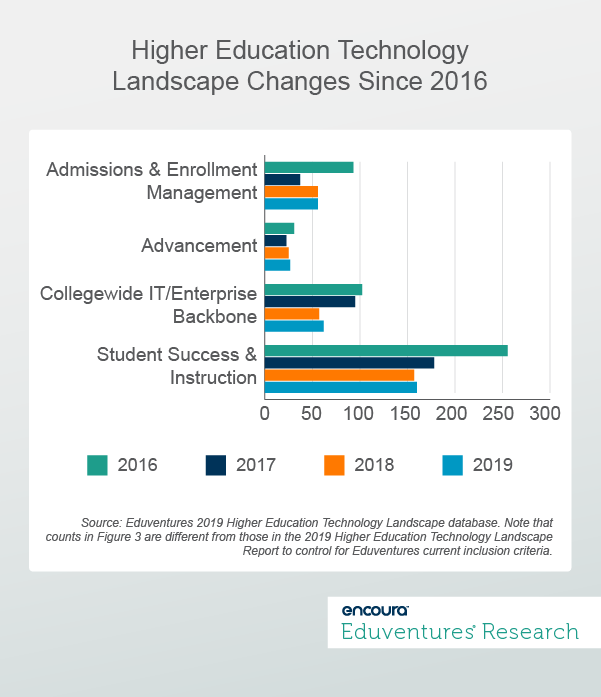

This year, we began to look longitudinally at the entries in our database to get a better sense of longer-term product trends. To recognize true changes in the Landscape, we decided to control for our evolving methodology and only include current segments and products that meet our existing definitions.

Since 2016, there has been a 22% reduction of entries across the four categories we track: Admissions & Enrollment Management, Advancement, College-Wide IT/Enterprise Backbone, and Student Success & Instruction (Figure 3).

Does this mean that institutions are less interested in student success this year than in previous years? Not necessarily. But we do suspect that institutions are increasing their focus on specific student success initiatives, such as preparing their students for the job market or developing better processes around the development and tracking of online learning curricula.

In an ever-changing market, tracking trends is critical to providing clarity. Look for more from Eduventures on this topic in 2020.

The Evolution and Migration of Students through the Recruitment Cycle

By Kim Reid

In 2019, I learned more about what really happens to students between application and enrollment. One of the big questions on our minds at Eduventures has been how students change and mature during their college search. In other words, what are their Student Mindsets™ and how do they change over the enrollment cycle? (If you’re not familiar with our research on Student Mindsets, here’s a brief summary.)

Eduventures Student Mindsets—assessed both at the time of application and time of the enrollment decision—capture this information independently, but, crucially, the data can be connected. This year, we examined two years of data for students who took both our Prospective Student Survey™ and our Survey of Admitted Students in the same enrollment cycle. This paired sample gave us deep insight into how students evolved their way of thinking about college.

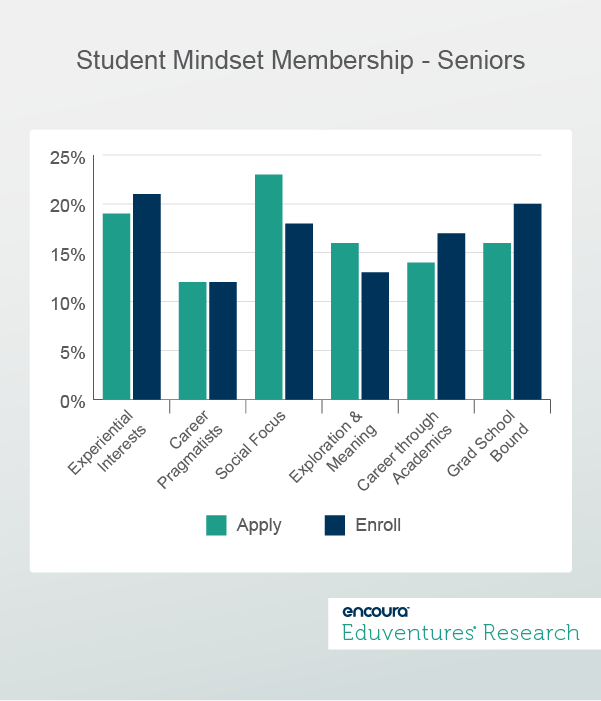

Figure 4 shows—at a high level—what happens between December and May of students’ senior years. Two Mindsets (Social Focus, and Exploration and Meaning) lose a significant proportion of students, while three Mindsets (Experiential Interests, Career through Academics, and Grad School Bound) gain a following.

We believe that as students go through college search they become more grounded in the real opportunities of college. Thus, they turn slightly away from the more social, experience-oriented Mindsets that are all about connecting with other students or making an impact on the world. Instead, as they learn about academics, internships, and career outcomes they may not have known about, they bend toward Mindsets that focus on tangible opportunities.

This is evidence of learning through the college search process. It can also be interpreted as evidence that college and university messaging really sinks in.

What you cannot see here is which specific students are in which Mindsets. This is where the story gets interesting. This research truly comes together when we examine the migration of students between the Mindsets. Which students stay the course in a Mindset? Which students migrate to another? And, why do these migrations occur?

That story is forthcoming in a future Eduventures report. Stay tuned!

The Call for Career Readiness Crescendos

By Michael Miller

In 2019, I learned that seemingly every entity involved in U.S. higher education—institutions, technology and service providers, students, and multiple levels of government—is putting increased emphasis on career readiness.

The question is, where is that emphasis being placed?

A major area of focus is making the job market more transparent and accessible to students. Students have more opportunities to engage with third parties that facilitate a direct connection to employers or highlight the specific skills careers require so that students may establish clearer career pathways. This is changing the traditional function of institutional career services.

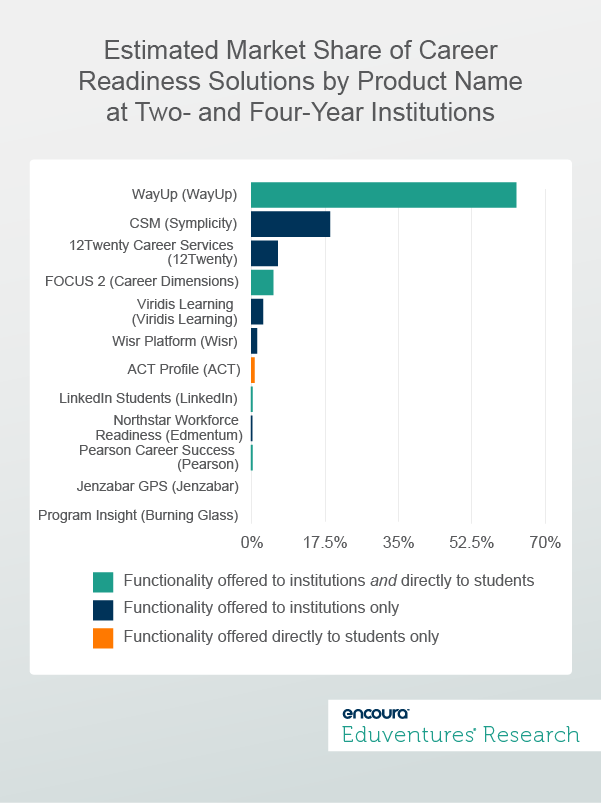

We highlighted this trend earlier this year in our Market Analysis report on Career Readiness Solutions. Figure 5 shows the estimated market share of career readiness technology solutions in 2019.

This data is just one indication that the use of relatively new solutions designed to directly connect students to jobs and alumni networks, like WayUp and Handshake (not displayed in Figure 5), has grown rapidly. More traditional solutions in use by career services administrators, such as CSM by Simplicity and 12Twenty Career Services, are still in wide use, but these solutions will increasingly face pressure to adapt to the changing landscape.

Additional emphasis on illuminating and improving the college-to-career connection can be seen across higher education, for example: Google’s expansion of community college partnerships, Amazon’s collaboration with Virginia colleges, and the Education Department’s College Scorecard, which now shows which majors at which institutions yield the highest paying jobs and graduates the most indebted students.

Preparing for inevitable shifts in employer needs and times when unemployment will be higher is critical. I believe we can expect to see two related developments in the coming years: First, third parties—be they service or technology providers or corporations seeking employees with specific skills—will increasingly build bridges with institutions to add more structure and transparency to career pathways. Second, as a knock-on effect of the first development, more institutions will migrate responsibilities of career preparation from career services to academic departments and their advisors.

Join us in Boston, June 3-5, 2020, as we convene eminent thinkers, leaders, and practitioners from across the higher education spectrum to examine and showcase the best ideas, old and new. If there is one event in higher ed you attend in 2020, make it Eduventures Summit.