Enrollment in US higher education has fallen for three years in a row. For traditional age students, the explanation is well-known: The country is in the midst of a slump in the number of 18-24 year olds, the economy is strengthening, and the “Great Recession” led to a peak in enrollments. These trends suggest the decline is temporary and stimulated by demography more than demand. Between 1992 and 1995, the only other time since World War II that total US enrollment declined three years in a row, circumstances were similar.

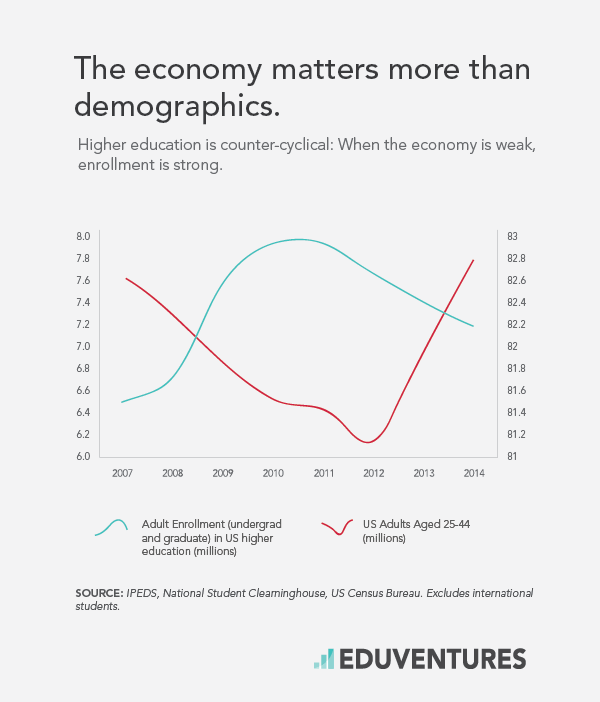

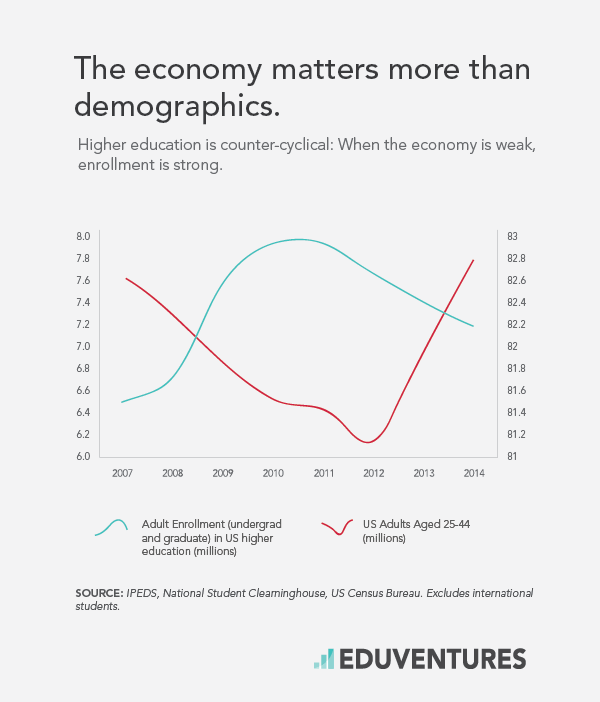

What about adult learners, students over the age of 25? Adult enrollment, representing about 40% of all students, has now fallen four consecutive years and fallen faster than traditional age student enrollment. This decline has impacted both undergraduate and graduate numbers. Yet the number of 25-44 year olds in the US, the core adult market, is now growing (see figure). What is going on? How can schools explain this trend and what can they do to arrest these falling numbers?

Economy Matters More Than Demographics

This chart suggests that the economy matters more than demographics. Higher education is counter-cyclical: When the economy is weak, enrollment is strong. For adults, higher education is primarily an economic calculus. So adult enrollment climbed dramatically as the “Great Recession” took hold from 2008 to 2010, despite a steady fall in the underlying population. Amid the decline in adult enrollments, the fact remains that adult enrollment is significantly higher than pre-recession levels. This results from three factors that continue to persuade adults that a return to school is a smart option: The recovery has been lackluster and uneven, there continues to be sufficient churn in the economy, and there remains steady disruption wrought by globalization and automation. When looking at the recent drop in adult enrollments, some higher ed sectors have been hit harder than others:- The drop-off has been most obvious at for-profit institutions, where adult enrollments declined 20% between fall 2010 and fall 2014.

- Adult enrollment at four-year public institutions fell by only about 2% annually from 2012.

- At four-year private institutions, enrollment actually grew a bit in 2013 and 2014.

School Actions Matter More Than Demographics

The US Census Bureau projects that the underlying population will continue to grow through 2034. It is logical to expect that stronger adult demographics will temper recent enrollment declines and drive future enrollment increases. That said, Eduventures research makes clear that adult enrollment have historically shown little relationship to demographics. In the 1990s, when the 25-44 year old population was growing and the economy improved, enrollment fell for much of the decade. In the 2000s, when adult demographics were flat, enrollment picked up, spurred by the for-profit school surge and the rise of online programs. The bottom line is that school actions and the economy are more important than demographics in the adult market. So how are schools trying to innovate in this market?- Value innovation. A growing number of universities are working on innovations that will help the adult market grow again. Eduventures characterizes these as value rather than delivery mode innovations. In the 2000s, the boom in adult enrollment driven by online programs and for-profit schools was about access and convenience, not about innovation on the fundamentals of teaching and learning. Like many schools, consumers now more clearly see the inherent benefit of conventional online programming as convenience, not quality. Individual online programs may or may not be high quality in the academic or pedagogic sense, but that has little to do with basic delivery mode.

- Balance. Today’s innovations—competency-based learning, high-end production values, blended learning, and adaptive learning, to name a few—take the accessibility and convenience of online for granted and build from there. Adults want to gain a credential as efficiently as possible, but they also want quality and to be engaged. Today’s innovations are attempting a better balance between convenience and quality and between cost control and student engagement. A low cost, self-paced competency-based degree that isolates students will not go mainstream. Adaptive learning without sufficient faculty and advising support privileges automation over learning.

- Degree vs. non-degree. A cautionary note is that some see the degree itself as a brake on innovation, in terms of time and cost. Universities are involved here too—through MOOCs and direct assessment—but sidelined elsewhere, such as in Udacity’s nanodegrees and Minerva’s cut-price “elite” liberal arts degree. Just as universities have always coexisted with other forms of postsecondary education and training, tomorrow’s adult market promises to be large and diverse enough to ensure winners of all shapes and sizes. Universities must be sensitive to where their conventions are part of the problem while holding fast to the enduring values of higher education, however they are packaged.