“What is going on in the noncredit market?”

This has always been one of our clients’ toughest questions. Noncredit courses and programs are seemingly always both part-of-the-furniture—gathering dust in some obscure corner of continuing education—and about to come out of left field—free from academic constraints, ready to shake-up credit complacency with faster, cheaper, and more timely offerings.

Like the certificate market, this market has forever been hampered by the noncredit curse: a lack of data. But this Wake-Up Call draws on a little-known source to throw some light on the noncredit conundrum.

Secret Source

Some sources reckon noncredit enrollment—dubbed the “hidden college” and spanning everything from workplace certifications to personal interest courses and agricultural extension to remedial classes, not to mention MOOCs—is substantial: five million students in community colleges alone, according to the American Association of Community Colleges.

But no four-year school association tracks noncredit. Noncredit offerings are not eligible for federal student aid, so the feds do not require schools to report noncredit enrollment.

So, what is this little-known data source? IPEDS (The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System). That’s right. The Department of Education’s infamous database, devoted to credits and degrees, does in fact contain some . Fittingly, this data is in a less-than-obvious place: the Human Resources section. It is one step removed from enrollment (focused on instructors rather than students), and is hard to find: type “noncredit” in the IPEDS search bar, and you get zero results. But that “zero” is not true.

Of course, we are not the first to “find” this data. It has been sitting there since about 2013, and noncredit wonks are intimately familiar with it.

Indeed, there is a report highlighting it. In January 2020, the National Postsecondary Education Cooperative (NPEC)—a voluntary organization set up in 1995 by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) to recommend refinements to the IPEDS data collection—published a report entitled Noncredit Enrollment and Related Activities. The report summarized noncredit market research, including some analysis of the 2017 IPEDS data on noncredit instructors, and recommended that future IPEDS surveys include noncredit students.

Afflicted by the noncredit curse, the NPEC report received almost no coverage, and was quickly lost in the pandemic maelstrom.

Three Big Questions

The IPEDS data on noncredit instructors bodes lots of useful analysis. This Wake-Up Call, factoring in the latest 2018 data, tackles three big questions, the answers to which normally seem out-of-reach:

- What does the noncredit instructor data tell us about the reality of noncredit enrollment?

- How have noncredit instructor numbers changed over time?

- Is the MOOC boom—the biggest noncredit fuss in a long time—visible in the data?

Can the IPEDS noncredit data help answer these questions? Let’s take a look.

1. What is the scale of noncredit enrollment?

In fall 2018, the most recent IPEDS data available, there were a little under 20 million credit students in U.S. higher education. If there really are five million noncredit students at community colleges, plus untold more—if proportionally fewer—at four-year schools, that suggests noncredit might account for at least six million students or 20-25% of total student headcount.

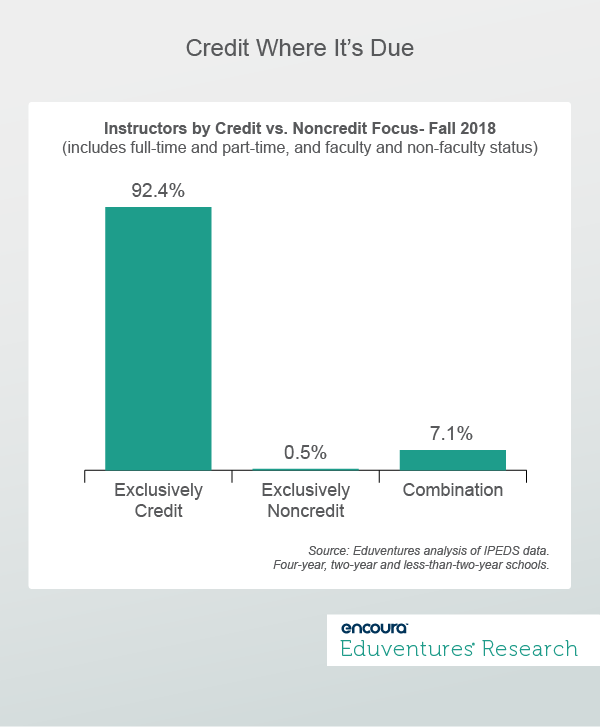

Do noncredit instructor numbers bear this out? Figure 1 implies no.

If 20-25% of higher education students are noncredit, how can fewer than 8% of instructors teach any noncredit classes, and only .5% solely teach noncredit?

On average, noncredit enrollment produces much lower full-time equivalent (FTE) instructor numbers than the credit norm. We do not know what proportion of “combination” instructor time is devoted to noncredit. If we assume that 3% of total instructor time is spent on noncredit, six million noncredit students would imply a mean of .14 instructor FTE.

That seems low, but within the realm of possibility for time-pressured adult learners paying out-of-pocket and ROI-focused employer sponsors. But such a modest rate of instructor FTE underlines why noncredit can be economically unattractive for schools, and reinforces why the percentage of exclusively credit instructors in Figure 1 stands at 92%.

2. Is the noncredit market growing?

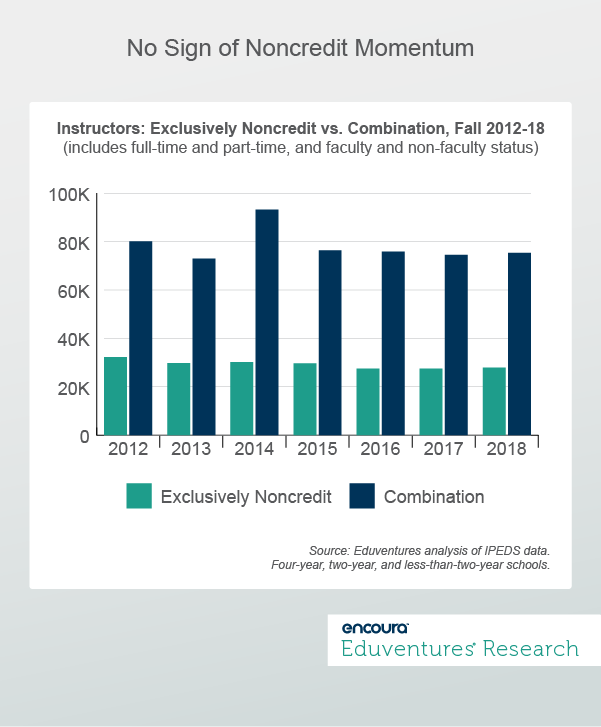

Figure 2 considers trends over time. Has the number of noncredit instructors grown in recent years?

Rather than growth, Figure 2 shows a slow decline in the number of exclusively noncredit instructors between fall 2012 and 2018, and fluctuation in the larger number of instructors who teach both credit and noncredit classes. On the face of it, Figure 2 does not support the notion that noncredit enrollment is surging in response to frictions in credit-land.

In fact, the instructor category that saw the biggest growth over the period was full-time, exclusively credit instructors.

Does all this throw cold water on noncredit cheerleaders? Not necessarily. Let’s turn to MOOCs.

3. What about MOOCs?

The bump in the number of combined credit and noncredit instructors in 2014—up 28% in a single year—follows the initial MOOC enthusiasm of 2012. Indeed, according to Figure 2, 2012 saw the second highest number of combined instructors, and the highest number of those engaged exclusively in noncredit. And it is at public and private nonprofit four-year schools, in the MOOC vanguard, that we see the 2014 growth.

So, does Figure 2 reflect the heady days of MOOC exuberance (2012), some deflation in 2013, and then recommitment and new university partners for Coursera and edX in 2014, churning out all those (noncredit) MOOC courses?

That would be a great story, but the noncredit curse strikes again.

Among Coursera’s first institutional partners—University of Michigan, University of Pennsylvania, and Stanford—not a single noncredit instructor, exclusive or combined, was reported between 2012 and 2018. The same is true for Harvard and University of California Berkeley, two of edX’s first partners.

Only MIT, another early edX partner, and Princeton, a first-round Coursera collaborator, show up in the data. MIT reported about 30 credit-noncredit combination instructors every year, as if the MOOC explosion was not in fact resounding from Cambridge. Only Princeton, which reported zero combined instructors in 2012 and 2013, 95 in 2014, 99 in 2015, and then zero thereafter, captures the rush of noncredit MOOC course development in those years, even though the other schools were as active, if not more so.

So why the spike in four-year school noncredit instructors in 2014? Examining the data at the institutional level reveals numerous schools that reported zero noncredit and combined instructors in 2012 and 2013 and then suddenly reported hundreds in 2014. By 2015, many of these schools reverted to zeros again. Some of this may be due to MOOC activity, but much may simply be uneven reporting.

No doubt many schools are diligent in accurately conveying their noncredit and combined instructor numbers. But there is clearly more noise than average in this data. The confluence of new reporting requirements, noncredit data out-of-place in an otherwise credit-oriented survey, and a backdrop of often limited noncredit tracking within institutions is a recipe for shaky results.

The problem is not confined to MOOCs. A noncredit study of state-level noncredit data found that Cornell University, across its multiple extension sites, offered 4.3 million contact hours in noncredit courses in 2012-13, more than all New York’s community colleges put together. Yet Cornell, according to my analysis, reported zero noncredit or combined instructors every year between 2012 and 2018. The report quotes a Cornell official as saying that the university submits only credit data to IPEDS. Extension is an entirely separate operation.

Even more jarringly, the big MOOC platforms announced tens of millions of learners between 2012 and 2018, the majority in noncredit courses and programs created by U.S. colleges and universities. Yet Figure 2 shows no sign of this dramatic enrollment surge.

This raises some important questions. Institutional faculty may have built the MOOC courses, but most of these courses are self-paced. A pre-packaged course from a star faculty member can be taken an infinite number of times without the faculty member lifting a finger. Perhaps the lesson from Figure 2 is that ramping up enrollment in self-paced noncredit courses does not require legions of new instructors.

If noncredit students were added to the IPEDS mix, as NPEC recommends, how should a university’s MOOC courses, with hundreds of thousands of students but no live instructors, be reported? MOOCs turn conventional student-to-faculty ratios on their heads. If the MOOC platform employs an army of support staff, should they be reported also? Many MOOC programs have credit and noncredit pathways. How should they be distinguished in the data? Excluding MOOC courses from IPEDS would avoid some headaches but leave out today’s most dynamic noncredit market.

The Bottom Line

The present noncredit instructor data in IPEDS is best thought of as a stage in a long-term effort to integrate the noncredit sector more fully into routine federal surveying. Advocates have been calling for a more expansive IPEDS for years, and NCES is doing its best to add to an already daunting instrument. The more noncredit reporting becomes a fact-of-life for Title IV-eligible schools, the better the data will be.

It is reasonable to mistake IPEDS for the nation’s postsecondary education database. In fact, IPEDS is a database of publicly supported postsecondary education. Plenty of additional postsecondary education goes on under the banner of colleges and universities, but it is federal funding rather than postsecondary reality that drives data collection.

The IPEDS noncredit instructor data may be far from perfect but—for the careful researcher—it offers invaluable insight into this most elusive of sectors, and is part of the valiant endeavor to finally defeat the dreaded noncredit curse once-and-for-all.

Never Miss Your Wake-Up Call

Learn more about our team of expert research analysts here.

Eduventures Chief Research Officer at ACT | NRCCUA

Contact

This recruitment cycle challenged the creativity of enrollment teams as they were forced to recreate the entire enrollment experience online. The challenge for this spring will be getting proximate to admitted students by replicating new-found practices to increase yield through the summer’s extended enrollment cycle.

By participating in the Eduventures Admitted Student Research, your office will gain actionable insights on:

- Nationwide benchmarks for yield outcomes

- Changes in the decision-making behaviors of incoming freshmen that impact recruiting

- Gaps between how your institution was perceived and your actual institution identity

- Regional and national competitive shifts in the wake of the post-COVID-19 environment

- Competitiveness of your updated financial aid model