“America is facing a workforce crisis with implications for economic competitiveness and national defense,” according to STEMconnector’s recent report covering the tech skills gap. “Some estimate up to 2.4 million STEM jobs go unfilled.”

While traditional colleges and universities have long played a key role in preparing students for careers in STEM fields, they have historically left the more technical (and increasingly in-demand) components—like basic coding skills or exposure to common technology solutions—to special focused colleges, third party providers, and two-year schools. But this is changing.

Many four-year schools have added these technical components to their curriculum or are beginning to invest in them. The question is, how?

While the existence of a skills gap and its perpetrators remain long-standing subjects of debate,

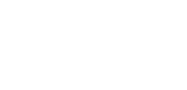

Figure 1, featuring job postings data across all industries, supports the claim that employers are increasingly looking to fill roles that require more technical skills. Another prime example is the growth in coding bootcamps, which graduated 23,000 students in 2019, a 49% year-over-year growth rate (37% on a same school basis).

The oft-cited “workforce of the future” and “skills gap” of the present refers to a broad number of items. It is important to note that the technology skills referenced here are those in-demand hard skills that are specifically related to software development, information technology, and data analysis. They include, but are not limited to: coding languages such as Python and SQL, and gaining familiarity with widely-used solutions like Salesforce and Tableau.

A Business Framework Reimagined for Higher Ed

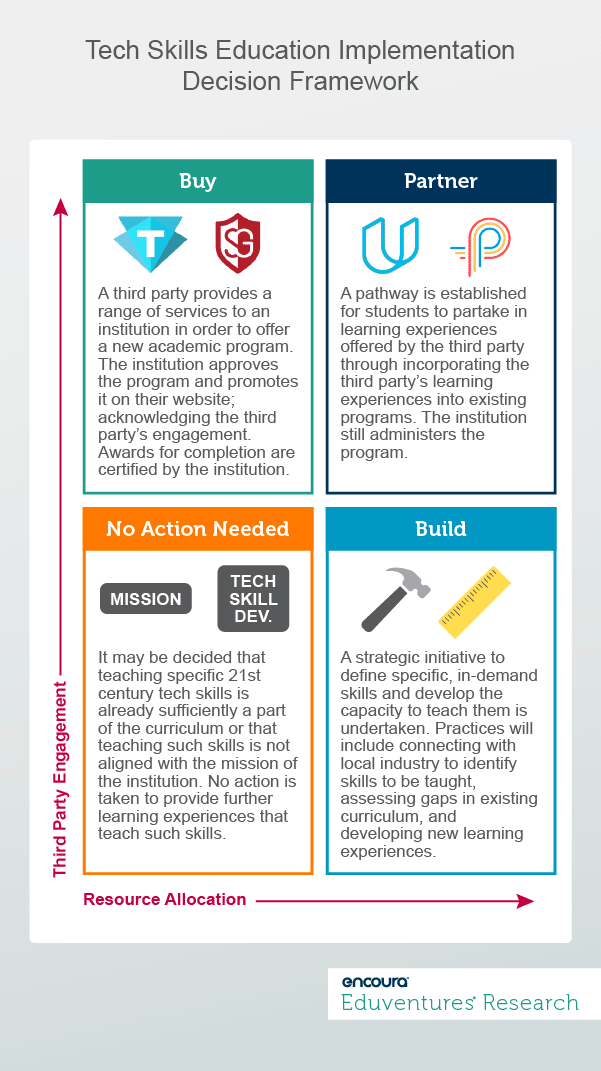

Eduventures often works with companies that are looking to expand into new markets, such as a predominantly hardware-focused company contemplating the development of lecture capture software. At this point, they often consider the common decision framework: build, buy, or partner?

Figure 2 translates this type of decision process for colleges and universities confronting the decision to include certain technical skills in their curriculum. While the decisions themselves—build, buy, or partner—remain the same, the rationale for each changes quite a bit.

So, which option is best for higher education institutions?

Building programs is the most labor- and cost-intensive. For institutions that have the resources and believe that technical skills development is directly aligned with their missions and goals, creating programs and the capacity to teach and administer them, in-house may be a good option. It could involve directly connecting with local industry—like Salt Lake Community College—or it may manifest itself in a re-think of curriculum, like Boise State’s “Data Science for Liberal Arts" certificate.

Buying, in this context, entails bringing on ready-made programs and delivery capabilities from a third party. The option to buy programs “out-of-the-box” does not necessarily require up-front capital; on the contrary, it can bring in additional revenue. The buy, in this example, is the institution’s enablement of a third party’s curriculum and services related to the enrollment management, marketing, and delivery of courses. In this framework, the buy decision is less resource intensive than partnering, since institutions get much of what they need to run the program from the third party. For example, University of California, Berkeley offers a coding bootcamp through Trilogy, a 2U company, and Kent State offers one through The Software Guild, a Wiley company.

Partnering usually involves providing access to third-party courses without accompanying services. It may involve incorporating third-party courses within pre-existing academic programs at the degree or certificate level like Oakland-based Merritt College’s partnership with Pathstream. Unlike “buying” a ready-made program, administrative services are generally the responsibility of the institution, while the courses are made available through the partnership.

Saying no is also, of course, an option. Adding or building the capacity to teach hard skills is not for every institution. Perhaps developing technical hard skills, or partnering with a third party in-and-of-itself, is not aligned with the mission. Should students wish to acquire such skills, they have abundant opportunities to do so elsewhere.

The Bottom Line

The recent success of bootcamps and the clear calls of both industry and students for work-ready skills show that demand for these skills is real. Institutions have a variety of options to provide students with opportunities to learn them, and the landscape of technical-skill providers will continue to evolve. New providers and new partnership and business models involving industry and third party education providers are certain to be on the horizon.

Bootcamps and technology-centric courses and certificates all too often stand outside of much of the non-STEM curriculum. Non-STEM students seeking to learn such skills often need to take extra courses, incurring extra costs.

This will also change. However they choose to add them, schools that can successfully weave components of a technical education into their non-technical curriculum—and successfully communicate that value proposition—may find themselves in higher demand, with graduates better prepared for the workforce.

Eduventures Senior Analyst at ACT | NRCCUA

Contact

Thursday, February 20, 2020 at 2PM ET/1PM CT

Admitted student survey data can provide enrollment leaders insight into why students enrolled in their institution -- and perhaps more importantly, why they didn’t -- but without benchmarks, an institution can only understand its result in isolation.

Inevitably, an institution is compelled to ask how its admitted student metrics look in comparison to other institutions in the same category. Using data from the Survey of Admitted Students™, our latest benchmark report outlines the nine key benchmarks that every college and university can use to inform recruitment, yield, and institutional identity.

In this webinar, Eduventures Principal Analyst Kim Reid will identify key strategic questions every enrollment leader should be asking to measure up the institution’s yield performance and how to take specific action to improve the next class.