The demise of Corinthian Colleges and ITT might be regarded as inevitable churn in a dynamic industry, but it also raises existential questions. The for-profit pitch is that many non-traditional students are better served by teaching-only, career-oriented institutions that emphasize the student as customer. Yet, the problem for the sector is twofold:

Let’s start with the Jack Welch Management Institute (JWMI). JWMI started out at Chancellor University, a now-closed, for-profit university, and became part of Strayer in 2011. The institute is the brainchild of Jack Welch, longtime CEO of General Electric (GE) known for dramatically increasing GE’s market valuation and culling under-performing managers and business units. Welch saw a need for a more hands-on business school, and he only considered a for-profit home for his institute, thinking it essential that JWMI practices what it preaches. While JWMI offers conventional master’s degrees and certificates, it is in other ways a departure among for-profit schools.

Although naming is common among the higher echelons of nonprofit b-schools, normally to honor a major donor, it is rare among for-profits. A name adds cache to a brand, so alignment with one of the best-known contemporary leadership thinkers is a coup. In this case, the JWMI MBA is priced higher than Strayer’s standard program.

Taken at face value, JWMI is doing well. Princeton Review ranked the institute #22 on its list of the best online MBAs, and LinkedIn named it the “most influential education brand” in 2015. Poets & Quants said the institute was one of the top 10 business schools to watch in 2016. JWMI claims it is one of the fast growing business schools in the world, with over 1,400 students.

Jack Welch is said to be involved in all aspects of the institute, a departure from the norm at nonprofits where donors fund big ideas but have little say over the details. Branding aside, what is the substance of Mr. Welch’s contribution? In a video, Mr. Welch talks about teaching students how to build “winning teams” and to learn things on Monday they can apply on Tuesday, and then return to class on Friday to discuss what worked.

These claims allude to a distinct approach to teaching and learning that is often missing among for-profits. While it is a match to the headlines of its guru’s best known books, it can also be tough to distinguish differentiated value from marketing. Students study 100% online, the specifics of which are not articulated, which may suggest the experience actually resembles that at other online schools. The value—to the student—of a for-profit business school, is not spelled out.

JWMI represents an intriguing direction for Strayer and will not be the last branded for-profit business school. Ashford University’s Forbes School of Business is a more recent example. JWMI has the potential to shake up a commoditized b-school market among for-profit and nonprofit schools alike, but must guard against being different in name only.

Let’s start with the Jack Welch Management Institute (JWMI). JWMI started out at Chancellor University, a now-closed, for-profit university, and became part of Strayer in 2011. The institute is the brainchild of Jack Welch, longtime CEO of General Electric (GE) known for dramatically increasing GE’s market valuation and culling under-performing managers and business units. Welch saw a need for a more hands-on business school, and he only considered a for-profit home for his institute, thinking it essential that JWMI practices what it preaches. While JWMI offers conventional master’s degrees and certificates, it is in other ways a departure among for-profit schools.

Although naming is common among the higher echelons of nonprofit b-schools, normally to honor a major donor, it is rare among for-profits. A name adds cache to a brand, so alignment with one of the best-known contemporary leadership thinkers is a coup. In this case, the JWMI MBA is priced higher than Strayer’s standard program.

Taken at face value, JWMI is doing well. Princeton Review ranked the institute #22 on its list of the best online MBAs, and LinkedIn named it the “most influential education brand” in 2015. Poets & Quants said the institute was one of the top 10 business schools to watch in 2016. JWMI claims it is one of the fast growing business schools in the world, with over 1,400 students.

Jack Welch is said to be involved in all aspects of the institute, a departure from the norm at nonprofits where donors fund big ideas but have little say over the details. Branding aside, what is the substance of Mr. Welch’s contribution? In a video, Mr. Welch talks about teaching students how to build “winning teams” and to learn things on Monday they can apply on Tuesday, and then return to class on Friday to discuss what worked.

These claims allude to a distinct approach to teaching and learning that is often missing among for-profits. While it is a match to the headlines of its guru’s best known books, it can also be tough to distinguish differentiated value from marketing. Students study 100% online, the specifics of which are not articulated, which may suggest the experience actually resembles that at other online schools. The value—to the student—of a for-profit business school, is not spelled out.

JWMI represents an intriguing direction for Strayer and will not be the last branded for-profit business school. Ashford University’s Forbes School of Business is a more recent example. JWMI has the potential to shake up a commoditized b-school market among for-profit and nonprofit schools alike, but must guard against being different in name only.

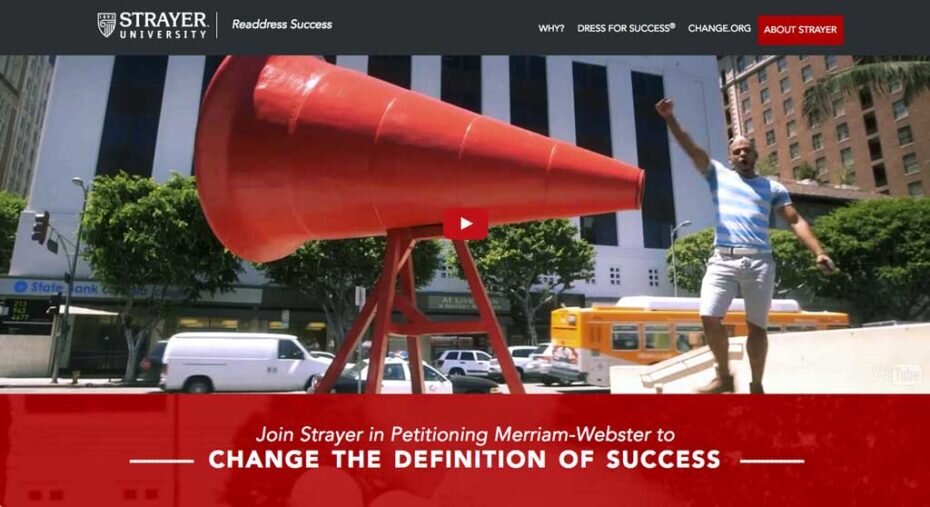

A second novel move by Strayer is the “Readdress Success” initiative, a clever marketing campaign to get the Merriam-Webster dictionary to change its definition of the word “success.” According to Strayer, the dictionary definition of success in terms of money, fame, and recognition is too narrow. It built a website featuring prospective students, various celebrities, and other public figures, reflecting on happiness, satisfaction, and relationships.

Strayer has been quite creative, setting up a giant megaphone on a city street and inviting passersby to shout into it their life’s goal. It has also persuaded people to phone a loved one—live on camera—to thank them for their support.

This approach is subtly different from the typical “get a degree, get a career” for-profit campaign. The effect is more emotional than transactional, and prompts a less cynical reaction. There is no more than an implicit link to the enrollment funnel.

While the best brands embody such intangibles, they also must deliver something tangible. “Readdress Success” is a great complement to the conventional Strayer brand, but the school is still selling degrees. How to clearly and compellingly foster, define, and report student outcomes is still on the horizon for for-profit schools, and higher education generally. Strayer is no exception.

A second novel move by Strayer is the “Readdress Success” initiative, a clever marketing campaign to get the Merriam-Webster dictionary to change its definition of the word “success.” According to Strayer, the dictionary definition of success in terms of money, fame, and recognition is too narrow. It built a website featuring prospective students, various celebrities, and other public figures, reflecting on happiness, satisfaction, and relationships.

Strayer has been quite creative, setting up a giant megaphone on a city street and inviting passersby to shout into it their life’s goal. It has also persuaded people to phone a loved one—live on camera—to thank them for their support.

This approach is subtly different from the typical “get a degree, get a career” for-profit campaign. The effect is more emotional than transactional, and prompts a less cynical reaction. There is no more than an implicit link to the enrollment funnel.

While the best brands embody such intangibles, they also must deliver something tangible. “Readdress Success” is a great complement to the conventional Strayer brand, but the school is still selling degrees. How to clearly and compellingly foster, define, and report student outcomes is still on the horizon for for-profit schools, and higher education generally. Strayer is no exception.

- Large numbers of nonprofit colleges and universities have emulated the for-profit approach, often at a lower price, making the typical for-profit school less distinctive. For-profits peaked at about 12% market share in 2010 and are now in retreat.

- The formula for commercial success in other industries—standardization, scale, and consolidation—has not played out in higher education. For-profit schools have yet to make a convincing case to students or government.

The Jack Welch Management Institute

Let’s start with the Jack Welch Management Institute (JWMI). JWMI started out at Chancellor University, a now-closed, for-profit university, and became part of Strayer in 2011. The institute is the brainchild of Jack Welch, longtime CEO of General Electric (GE) known for dramatically increasing GE’s market valuation and culling under-performing managers and business units. Welch saw a need for a more hands-on business school, and he only considered a for-profit home for his institute, thinking it essential that JWMI practices what it preaches. While JWMI offers conventional master’s degrees and certificates, it is in other ways a departure among for-profit schools.

Although naming is common among the higher echelons of nonprofit b-schools, normally to honor a major donor, it is rare among for-profits. A name adds cache to a brand, so alignment with one of the best-known contemporary leadership thinkers is a coup. In this case, the JWMI MBA is priced higher than Strayer’s standard program.

Taken at face value, JWMI is doing well. Princeton Review ranked the institute #22 on its list of the best online MBAs, and LinkedIn named it the “most influential education brand” in 2015. Poets & Quants said the institute was one of the top 10 business schools to watch in 2016. JWMI claims it is one of the fast growing business schools in the world, with over 1,400 students.

Jack Welch is said to be involved in all aspects of the institute, a departure from the norm at nonprofits where donors fund big ideas but have little say over the details. Branding aside, what is the substance of Mr. Welch’s contribution? In a video, Mr. Welch talks about teaching students how to build “winning teams” and to learn things on Monday they can apply on Tuesday, and then return to class on Friday to discuss what worked.

These claims allude to a distinct approach to teaching and learning that is often missing among for-profits. While it is a match to the headlines of its guru’s best known books, it can also be tough to distinguish differentiated value from marketing. Students study 100% online, the specifics of which are not articulated, which may suggest the experience actually resembles that at other online schools. The value—to the student—of a for-profit business school, is not spelled out.

JWMI represents an intriguing direction for Strayer and will not be the last branded for-profit business school. Ashford University’s Forbes School of Business is a more recent example. JWMI has the potential to shake up a commoditized b-school market among for-profit and nonprofit schools alike, but must guard against being different in name only.

Let’s start with the Jack Welch Management Institute (JWMI). JWMI started out at Chancellor University, a now-closed, for-profit university, and became part of Strayer in 2011. The institute is the brainchild of Jack Welch, longtime CEO of General Electric (GE) known for dramatically increasing GE’s market valuation and culling under-performing managers and business units. Welch saw a need for a more hands-on business school, and he only considered a for-profit home for his institute, thinking it essential that JWMI practices what it preaches. While JWMI offers conventional master’s degrees and certificates, it is in other ways a departure among for-profit schools.

Although naming is common among the higher echelons of nonprofit b-schools, normally to honor a major donor, it is rare among for-profits. A name adds cache to a brand, so alignment with one of the best-known contemporary leadership thinkers is a coup. In this case, the JWMI MBA is priced higher than Strayer’s standard program.

Taken at face value, JWMI is doing well. Princeton Review ranked the institute #22 on its list of the best online MBAs, and LinkedIn named it the “most influential education brand” in 2015. Poets & Quants said the institute was one of the top 10 business schools to watch in 2016. JWMI claims it is one of the fast growing business schools in the world, with over 1,400 students.

Jack Welch is said to be involved in all aspects of the institute, a departure from the norm at nonprofits where donors fund big ideas but have little say over the details. Branding aside, what is the substance of Mr. Welch’s contribution? In a video, Mr. Welch talks about teaching students how to build “winning teams” and to learn things on Monday they can apply on Tuesday, and then return to class on Friday to discuss what worked.

These claims allude to a distinct approach to teaching and learning that is often missing among for-profits. While it is a match to the headlines of its guru’s best known books, it can also be tough to distinguish differentiated value from marketing. Students study 100% online, the specifics of which are not articulated, which may suggest the experience actually resembles that at other online schools. The value—to the student—of a for-profit business school, is not spelled out.

JWMI represents an intriguing direction for Strayer and will not be the last branded for-profit business school. Ashford University’s Forbes School of Business is a more recent example. JWMI has the potential to shake up a commoditized b-school market among for-profit and nonprofit schools alike, but must guard against being different in name only.

Strayer “Readdresses Success”

A second novel move by Strayer is the “Readdress Success” initiative, a clever marketing campaign to get the Merriam-Webster dictionary to change its definition of the word “success.” According to Strayer, the dictionary definition of success in terms of money, fame, and recognition is too narrow. It built a website featuring prospective students, various celebrities, and other public figures, reflecting on happiness, satisfaction, and relationships.

Strayer has been quite creative, setting up a giant megaphone on a city street and inviting passersby to shout into it their life’s goal. It has also persuaded people to phone a loved one—live on camera—to thank them for their support.

This approach is subtly different from the typical “get a degree, get a career” for-profit campaign. The effect is more emotional than transactional, and prompts a less cynical reaction. There is no more than an implicit link to the enrollment funnel.

While the best brands embody such intangibles, they also must deliver something tangible. “Readdress Success” is a great complement to the conventional Strayer brand, but the school is still selling degrees. How to clearly and compellingly foster, define, and report student outcomes is still on the horizon for for-profit schools, and higher education generally. Strayer is no exception.

A second novel move by Strayer is the “Readdress Success” initiative, a clever marketing campaign to get the Merriam-Webster dictionary to change its definition of the word “success.” According to Strayer, the dictionary definition of success in terms of money, fame, and recognition is too narrow. It built a website featuring prospective students, various celebrities, and other public figures, reflecting on happiness, satisfaction, and relationships.

Strayer has been quite creative, setting up a giant megaphone on a city street and inviting passersby to shout into it their life’s goal. It has also persuaded people to phone a loved one—live on camera—to thank them for their support.

This approach is subtly different from the typical “get a degree, get a career” for-profit campaign. The effect is more emotional than transactional, and prompts a less cynical reaction. There is no more than an implicit link to the enrollment funnel.

While the best brands embody such intangibles, they also must deliver something tangible. “Readdress Success” is a great complement to the conventional Strayer brand, but the school is still selling degrees. How to clearly and compellingly foster, define, and report student outcomes is still on the horizon for for-profit schools, and higher education generally. Strayer is no exception.