State legislators have always cared about higher education—proudly cutting ribbons at new campus buildings and burnishing state aid programs—but have deferred to institutions on academic programming. A higher education coordinating board might oversee new program approvals, but senators were above the fray.

No more.

In recent months, legislators in Indiana and Ohio have passed bills requiring state colleges and universities to eliminate low-enrollment programs. Utah cut college budgets by 10%, promising reinvestment in high-performing programs. Politics is a driver, but after years of program growth running ahead of enrollment, lawmakers may have a point.

Which state systems are vulnerable to the charge of “too many programs?” How are higher education leaders responding to these new directives, and is there opportunity amid the cuts?

IOU

In March, the Utah Legislature cut $60 million or 10% of instructional funding at public colleges and universities. The money will be reinvested in programs that boost the regional economy and demonstrate good student outcomes. In response, University of Utah, the flagship, eliminated 94 programs across 10 schools and colleges. The list included humanities and arts programs but also some STEM and business offerings.

The same month, Ohio passed legislation requiring state colleges and universities to eliminate any undergraduate degree programs that conferred an average of fewer than five degrees annually over a three-year period. In April, Indiana enacted termination thresholds of 10 students a year over three years for Associate degree programs, 15 for bachelor’s programs, and seven for master’s degrees. In response, the Indiana University System is cutting or merging 400 programs.

In all three states, faculty complain that they were not consulted and worry that promising programs might be cut before their prime. Critics contend that the new laws ignore how general education courses and minors can boost the productivity of low-enrollment majors. But lawmakers are unmoved

USA

All three states cite falling student demand, funding constraints, and skepticism that programs lacking a clear career outcome are a good value for taxpayers as their rationales. As senators in other states watch with interest, it is worth asking how valid these concerns are in each state.

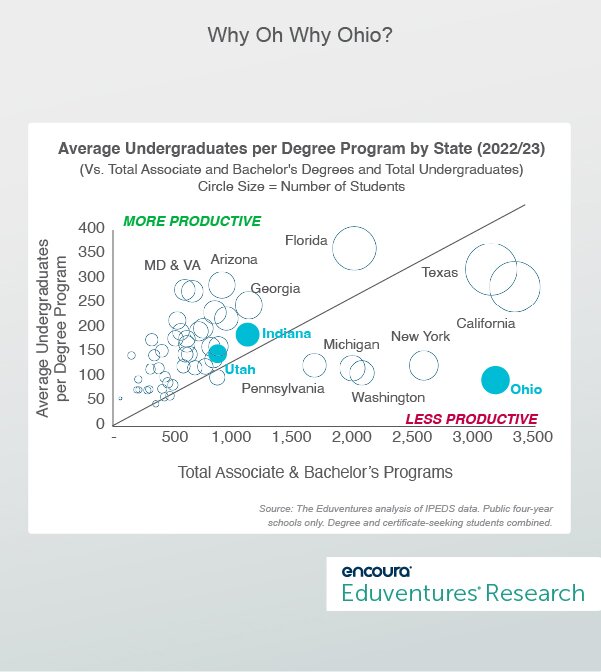

Figure 1 compares total undergraduate degree-seeking students, total associate and bachelor’s programs, and students per program for academic year 2022/23 across states. While enrollment scale aids program productivity, there are obvious outliers.

Figure 1.

Small states with fewer students have less productive programs and vice versa. But the lawmakers of Ohio are understandably concerned: the state’s four-year public institutions report only 94 students per program compared to a national average of 179. The state’s system is less productive than neighboring West Virginia, despite having six times as many students.

The other two public systems subject to lawmaker scrutiny—Indiana and Utah—look average on Figure 1. Republican skepticism of higher education (Indiana, Ohio, and Utah are all GOP-run) no doubt plays a role. Indiana’s latest budget slashes taxes and spending across the board, in tune with the Trump administration’s One Big Beautiful Bill.

Some public higher education systems look genuinely bloated, but in today’s climate (demographic, funding, political) any system is vulnerable to intervention. That’s the lesson of Figure 1.

Small Programs

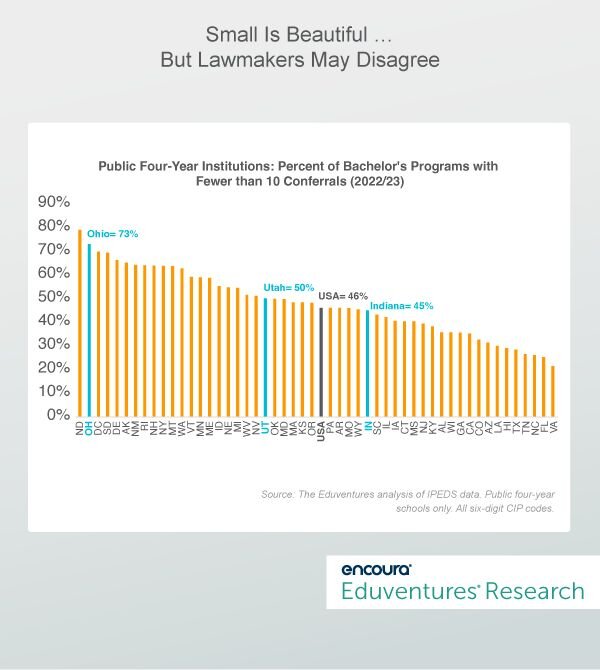

What about the accusation that colleges sustain numerous low enrollment programs? Figure 2 ranks states from highest to lowest share of bachelor’s degree programs that conferred fewer than 10 degrees in 2023.

Figure 2.

In North Dakota, almost four-in-five bachelor’s programs conferred fewer than 10 degrees in 2023 compared to close to one-in-five in Virginia. Lower population states cluster to the left of Figure 2, but New York and Washington also feature. The largest states show on the right side of Figure 2, but Hawaii and Louisiana buck the trend. Some mid-sized states (e.g., North Carolina, Tennessee) appear more consolidated than others (e.g., Michigan, Minnesota).

Again, Ohio lawmakers seem to be onto something: almost three-quarters of bachelor’s programs at the state’s public four-year schools report low conferrals. Indiana and Utah look average. (Florida—which excels on both Figures—has regulated program rationalization since the 1970s).

By major field of study, 85% of Area/Ethnic/Gender studies programs (a popular target of lawmaker ire) conferred less than 10 bachelor’s degrees nationally in 2023 compared to only 28% in Business. Ratios diverge by state: Ohio reports the third highest number of “Area” programs nationally and 97% confer few degrees. There are only eight such programs in Utah, but only a quarter are “too small.” South Dakota might be judged to have too many Business programs—69% are “too small.”

Notionally “in-demand” fields such as Healthcare and Computing also encompass significant proportions of small programs: 35% and 37% respectively, with wide variations by state.

The Bottom Line

Over the past decade, total bachelor’s conferrals at public four-year institutions grew 12% (2023 vs. 2014), while total bachelor's programs offered grew 18% (50% faster). New programs can boost enrollment but risk cluttering an untended portfolio. Expect more state lawmakers to pay attention. Politics may cloud thinking, but the data suggests that some systems have questions to answer on productivity.

Institutional leaders would be wise to see opportunity. External pressure can help cut through thickets of internal decision-making. Adjacent programs accumulated (often in different departments) over time might benefit from a merger. The same may be true for some programs “duplicated” across systems.

The major-centric concept of programming might be judged out-of-step with employer interest in student adaptability and core skills. Not more “General Studies” degrees, but perhaps a cross-disciplinary synthesis that leverages the assets of a comprehensive university without the programmatic fragmentation. Faculty interest can be accommodated at the course and program levels. A “comprehensive” university might take different forms.

It is ironic that just as AI gives schools the ability to speed up program creation, a rush of new programs is the last thing most schools need. But AI can help refine, rationalize, and innovate, too.

Of course, the data may be misleading. Program definitions and reporting may be inconsistent between states, and the role of two-year and private schools may explain patterns in some jurisdictions. An online program may be thriving, while the campus version lags. Tallying programs and conferrals may overlook the contribution of “too small” programs to minors, non-degree programs, and General Education.

But do not expect lawmakers to appreciate such nuances. Enrollment and funding pressure are real and growing—never mind the politics.

Public or private, bachelor’s or master’s, simply adding programs is no longer a smart strategy for colleges and universities. Rethinking what a “program” is and how programs can make better use of resources are key to crafting a compelling student experience and brand. Involving enrollment management and marketing departments in program discussions can help balance faculty interest and financial viability.

Bottom line: Higher education has too many programs. The opportunity is to figure out how fewer programs can mean better programs.

Looking to launch or refine an academic program? Whether you’re deciding on the right modality, identifying your program’s audience, or expanding into new markets, our experts deliver research-driven insights to guide your strategy. With our in-depth studies, you’ll uncover opportunities to grow your reach and meet your institutional goals with confidence.