Ever since John Harvard in 1638 bequeathed his library and half his estate to the fledgling college that would bear his name, American higher education has been a story of slow but inexorable expansion.

Exclusivity—college only for the faithful, men, whites, the wealthy, the young, the able-bodied, or the brilliant—has gradually conceded to greater inclusivity. Innovation meant more and larger colleges and universities, and wider access to degrees. Higher education expansion became a measure of economic and social progress.

But the work is unfinished. Underscored by the COVID-19 pandemic, higher education is still a long way from being truly inclusive, equitable, or optimal. In my session at tomorrow's Eduventures Summit Virtual Research Forum, I will argue that we are living in the early years of a new era of “college alternatives” that are propelling higher education forward.

Is this bad news for colleges and universities?

The Long Arc of Higher Education Innovation

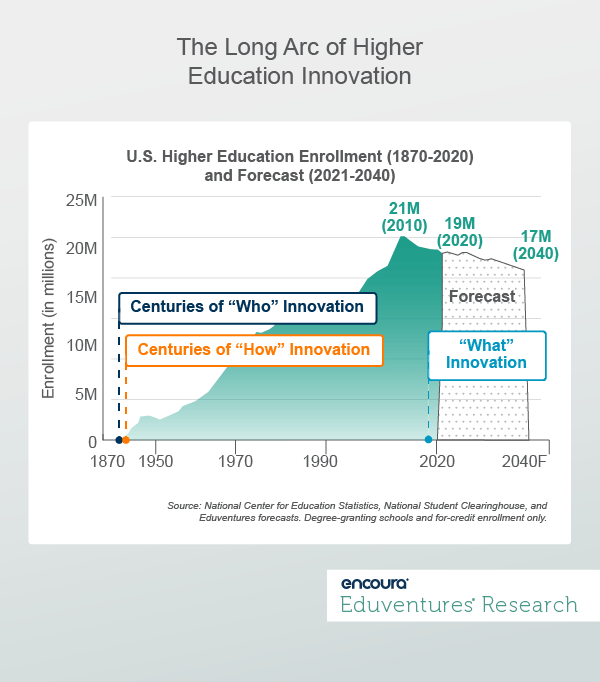

The unwavering logic of higher education expansion is now innovating beyond “college,” “university,” and “degree.” These college alternatives are the missing link in explaining the past decade’s enrollment shortfalls.

Some incumbents are on the cutting-edge of these trends.

The history of higher education enrollment can be reduced to three impulses:

- Widening “Who” Gets In: overcoming a host of religious, gender, racial, social, and other restrictions

- Rethinking “How” Higher Education is Provided: (in order to widen access): broadening to new kinds of institutions, commuter students, part-time study, distance learning, credit for prior learning, support services, etc.

- Reimagining “What” Higher Education Is: (in order to widen access further still): starting with the premise that for a growing number of current and prospective students, the fundamentals of “college,” “university,” and “degree” are themselves barriers to inclusion

The “Who” and “How” impulses dominated higher education expansion into the early 21st century. Colleges, universities, and degrees have long been able to shift and flex to accommodate ever-more diverse students and modes of participation. That capability—battling cost, time, and regulatory constraints—may have reached its limit. A bachelor’s degree defined as 120 credits can be manipulated only so far, and the dismal completion rates for many less traditional students and programs is testimony to the problem.

U.S. higher education is used to seemingly endless enrollment growth. Between 1952 and 2010, total higher education enrollment fell only six times, by modest amounts, and never for more than three years in a row. Between 2010 and 2020, total enrollment fell 10 years straight, a 10% drop in total.

Figure 1 shows that the enrollment declines of the past decade—notably among adults without a college degree and community college enrollment generally— are not merely functions of a population slump or low unemployment, both important trends, but consumer choice in a blossoming new era of innovation.

In my Summit presentation, College Alternatives: Sizing Up Demand, Models and Pathways, I will also argue that, despite headline growth, there is hidden enrollment decline at the graduate level, connected to the much-discussed parallel surge of non-degree innovation.

Eduventures forecasts (as shown in Figure 1) that “conventional” higher education enrollment will continue to (slowly) shrink in the coming decades in the wake of cohort decline and college alternatives.

The post-2010 enrollment losses, compounded by the pandemic, are not only a chronicle of nonconsumption—individuals not enrolling in degree programs at all or four-year school expansion at the expense of two-year schools—but also a tale of new providers, programs, and credentials not captured in conventional data.

What are these alternative providers, programs and credentials? Eduventures distinguishes three types:

Type 1: Save & Mix

(First Semester/Year/College Alternatives)

Target: High schoolers and current/prospective, traditional-aged undergraduates

Pitch: Save time and money toward a bachelor’s degree; personal development, belonging, and cultural fit; and/or mix-up the conventional college experience

Examples: Degrees of Freedom, Verto Education, YearUp, Minerva

Type 2: Learn & Work

(Study-Work Experience Combinations Tied to Subsequent Employment)

Target: Less “traditional” traditional-aged and adult current/prospective undergraduates

Pitch: Learning dedicated to practical skills development, job placement, and career pathways

Examples: Apprenticeships, Google certificates, bootcamps

Type 3: Lifelong & Just-in-Time

(On-Demand, Short, Inexpensive Upskilling Courses)

Target: People with a bachelor’s degree or higher

Pitch: Learning bursts to drive job performance and career advancement

Examples: Microcredentials

These college alternatives span various sectors, datasets, and funding models, proliferating in the cracks and fissures of mainstream higher education. Most currently fall outside of federal student aid, and some would rather evolve novel pricing and funding models than ride the trade-offs of government support.

In essence, these alternative providers offer programming at a pace, price, and intensity designed to meet specific needs and that most colleges and universities cannot (and are not intended to) match. Many students want degrees and will continue to do so, or desire a degree with some alternative features, but many want and need something different.

Research by Eduventures confirms that some “college alternatives” are growing fast: fast enough to help explain why certain strands of conventional college enrollment are down. I will run the numbers in my Summit presentation.

The Bottom Line

Strange as it might seem, college alternatives are good news for colleges and universities. Institutional models that try to be everything to everyone undermine outcomes and stretch credulity—a key reason why community college and adult undergraduate enrollment has cratered in recent years. The long arc of higher education innovation is working as intended.

College alternatives are also good news because they stimulate new demand and open up fresh degree pathways. Creative combinations of degrees and alternative elements (e.g., bootcamps, apprenticeships, microcredentials) are already taking shape.

Many of the nation’s leading universities are in the vanguard of the microcredential charge with a multitude of engaging, high production value courses and programs in in-demand fields. Making the “best” colleges more accessible fulfills the logic of the long arc.

New competition will help colleges and universities to update and polish their value propositions. Having a host of college alternatives as points of departure aids sharper differentiation and clarity of purpose.

But, there will be winners and losers: institutions that exemplify the best of neither degrees nor alternatives will face an existential challenge. Of course, some of today’s alternatives will fail or prove marginal.

Higher education expansion will continue on, raising up talent, and widening opportunity. From today’s hotbed of innovation, inside and outside colleges and universities, there will be fashioned the exciting next chapter in the American higher education story.

Join us for Eduventures Summit 2021 Virtual Research Forum tomorrow, June 16, to learn more about college alternatives. You will also hear a conversation with legendary filmmaker Ken Burns, a keynote from Yale Professor of Psychology Laurie Santos on student well-being, and from our President Panel.

Never Miss Your Wake-Up Call

Learn more about our team of expert research analysts here.

Eduventures Chief Research Officer at Encoura

Contact

Tuesday, June 22, 2021 2PM ET/1PM CT

Presenters will provide an overview of the results of the CHLOE 6 Survey of Chief Online Learning Officers. The survey investigated how institutions responded to the Covid-19 pandemic in the 2020-2021 academic year and how the pandemic impacted their plans for the future.

Presented by Bethany Simunich, Director of Research and Innovation at Quality Matters, and Richard Garrett, Eduventures Chief Research Officer at ACT | NRCCUA.

The Program Strength Assessment (PSA) is a data-driven way for higher education leaders to objectively evaluate their programs against internal and external benchmarks. By leveraging the unparalleled data sets and deep expertise of Eduventures, we’re able to objectively identify where your program strengths intersect with traditional, adult, and graduate students’ values, so you can create a productive and distinctive program portfolio.