The reporting deadline for the new federal Financial Value Transparency (FVT) and Gainful Employment (GE) metrics —recently pushed backed to January 15, 2025—is not far away. This is the U.S. Department of Education’s (Department) most ambitious attempt yet to shine a light on program outcomes across higher education.

The new rules cover all types and levels of programs, but the Department has made clear that online programs need closer oversight. Various new online-skeptical regulations—like challenging interstate reciprocity norms for distance programs, or requiring separate distance student reporting—underscore the point.

The latest College Scorecard data on graduate wages and student loan debt—the basis for these metrics—was published in June. Do the numbers justify federal anxiety about distance learning?

Yes, it affects you, too!

The U.S. Department of Education’s latest effort to weed out poor-return programs and improve student decision-making goes far beyond similar regulations from the 2010s. The new rules encompass all degree and non-degree programs—undergraduate and graduate—that use federal student aid at public, private, and for-profit colleges and universities.

Programs will be judged on:

- Debt-to-Earnings Ratio – no more than 20% of disposable income or 8% of total income.

- Earnings Premium – median graduate earnings must exceed the median for Americans aged 25-34 with no more than a high school diploma.

Only programs that fall under “Gainful Employment” (for-profit programs and non-degree programs at nonprofits) risk loss of federal aid, but FVT rules oblige the Department to disclose subpar outcomes data to prospective students. Prospective students wishing to enroll in failing FVT graduate and non-degree programs must acknowledge having seen the outcomes data before the Department will furnish aid.

Programs with fewer than 30 completions over the previous four years are excluded.

(Of course, a Trump win in November could be the death knell for FVT/GE but let us proceed with the status quo).

Online programs are of particular interest, as this quote from the Department ahead of the 2024 negotiated rulemaking on “Program Integrity and Institutional Quality” shows:

Currently, the Department has very limited data on students enrolled in distance education, which limits the Department’s ability to answer important questions about student pathways and outcomes through in-person, distance, and hybrid education.

What does the College Scorecard data tell us about online program outcomes?

The Scorecard distinguishes students enrolled in three types of programming: 1) fully online programs, 2) programs offered both online and on campus, and 3) campus-only programs.

Eduventures’ latest Online Higher Education Market Update report included analysis of some of this data but appeared before the latest release. For the first time, the new College Scorecard data includes wages and debt five-years post-graduation.

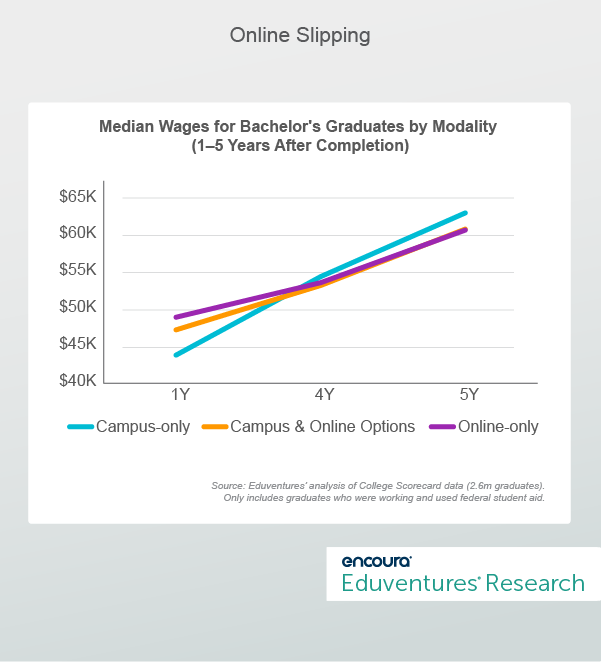

Let us start at the bachelor’s level. Figure 1 shows median wages for bachelor’s graduates by modality one, four, and five years after completion (for cohorts completing in 2015 and 2016).

Figure 1.

Counterintuitively, online-only graduates outearn others one-year post-completion, reporting 12% higher average earnings than campus-only peers. Graduates of online-only programs are typically older than average, perhaps conferring an early salary advantage. But five years out, campus-only graduates take the lead. The results are similar regardless of sector.

Regardless of modality, median wages climb strongly over time (up 41% between year one and year five), suggesting solid return-on-investment. The campus-only versus online-only gap widens over time but is modest (3.7% in year five).

The Low-Income Conundrum

Online-only bachelor’s graduates are more likely to be low income: 52% of campus-only graduates received a Pell Grant, but the ratio was 72% for online-only graduates.

Does this help explain the online-only wage deficit? It does not.

Pell students from campus-only programs outearned Pell students from online-only programs by 6.2% in year five. A gap remains even when isolating fields of study commonplace online, such as business, computing, and nursing.

But the picture is different for online-only non-Pell graduates, who sustain a lead (if a narrowing one) over non-Pell graduates from campus-only or multiple modality programs, outearning campus-only graduates by 3.4% in year five.

How to explain this?

One thought is that low-income students are more likely to struggle with online learning. Restricted computer and Internet access may negatively impact online study, undermining learning and earning. Pell graduates who attended campus-only programs might be assumed to have faced comparable resource challenges, hinting that the online learning experience may itself often be a negative for less-prepared students with limited financial means.

Are there often “too many” low-income students in online programs? Greater background diversity on campus may make for a more stimulating setting for learning.

Non-Pell online-only graduates may benefit not only from better technology but from a loftier start on the career ladder than that enjoyed by the typical Pell students studying online. The convenience of online programs is universally valuable, but some students are better positioned to thrive in this environment.

Online-only bachelor’s graduates borrow 12% more on average (from federal sources) than their campus-only peers and are more likely to have debt from a prior institution. This is consistent with the lower income and older profile of online-only students.

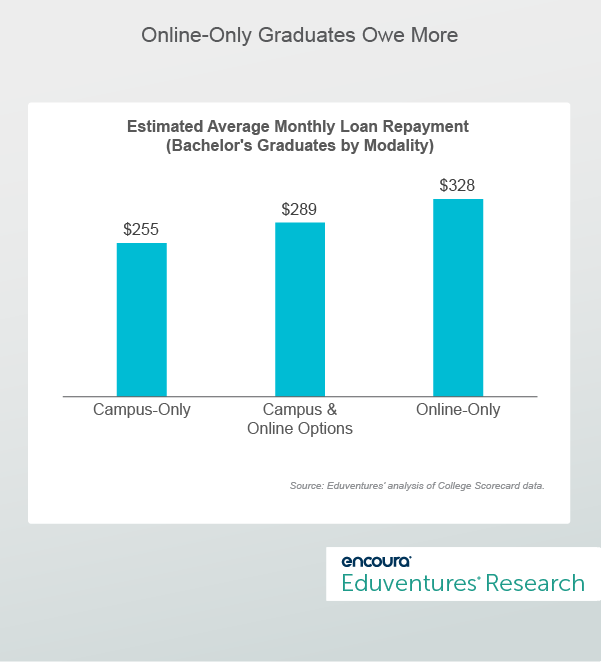

Figure 2 shows the Department’s “estimated” average monthly loan repayment for bachelor’s graduates by modality.

Figure 2.

The typical monthly payment for online-only programs is estimated to be 29% higher than that for campus-only programs. Most online-only bachelor’s graduates earn less but owe more.

Is higher average online graduate debt offset by lower online program prices? According to the Scorecard, the average net price for online-only institutions—public or private—is lower than the net price for campus-based schools, suggesting that online delivery has a positive impact on student debt.

Online-only graduates are somewhat more likely than average to have reduced their loan balances four years after college, reinforcing the case for decent earnings ROI.

But the combination of more low-income students, lower earnings post-graduation, and higher average student debt makes more expensive online-only bachelor’s programs vulnerable to exceeding the new GE/FVT debt/earning thresholds.

Eduventures’ initial analysis suggests that a third of institutions with data fail the total income debt-to-earnings measure (an average across all online-only bachelor’s programs).

The Bottom Line

In many ways, the latest College Scorecard data is good news for online learning. Graduates of online-only programs exhibit strong median wage growth in the years following graduation. Even when they trail their campus-only counterparts, the gap is modest.

But—because online holds disproportionate appeal to low-income students—it is problematic that Pell graduates from online-only bachelor’s programs earn less than not only their non-Pell peers, but less than Pell graduates from campus-only programs, even when controlling for fields of study common online. Not much less, but enough to fuel federal disquiet about online students.

Online-only graduates owe more than average and have higher estimated monthly student loan payments. This is consistent with higher Pell ratios. But if Pell students earn more post-graduation after attending a campus-only program, should low-income students be less enthusiastic about online?

Remember that it was as recently as 2008 that online-only programs became eligible for federal student aid. Rather than be surprised that the Department is now asking questions about modality, higher education should be surprised that it took this long.

Most institutions and programs will do fine on the new Financial Value Transparency metrics, regardless of modality, but more expensive programs attracting low-income students face some challenging conversations.

To discuss what the College Scorecard says about online or other programs at your institution, please contact your Client Research Analyst.

CHLOE 9: Strategizing the Future of Higher Education Through Online Learning

Learn what online higher education leaders from across the U.S. had to say in this year’s CHLOE 9 (Changing Landscape of Online Education) Survey.