Super AI tutors, expanded federal non-degree funding, and a paradigm shift in bachelor’s degree strategy … these were my three higher education predictions for 2024.

How did I do?

1.) A leading online school will launch a social teaching and learning model powered by AI. PARTIALLY RIGHT.

I see no more than tentative signs of next-generation AI tutors at top online institutions, but these schools are AI-active in other ways.

2.) “Short-Term Pell” will finally pass, fueling the non-degree market. WRONG.

“Short-Term Pell,” the bid to expand federal student aid to non-degree programs shorter than sixteen weeks, did not make it to the statute book, but a second Trump administration may prove the missing impetus.

3.) After decades of diversification, specialization will be the new bachelor’s strategy. RIGHT.

The latest data supports my prediction that we are in a new era of program focus over program diversification.

Prediction 1: A leading online school will launch an AI-powered social teaching and learning model.

The potential for game-changing AI tutors seems obvious: many students struggle, human tutors are effective but expensive and hard to scale, and recent technical advances suggest automated, low-cost, personalized solutions. An online university might pioneer such innovation.

So, have leading online schools jumped on board? Not really.

I reviewed the websites and announcements of 10 institutions (American Public University System, Arizona State University (ASU), Capella University, Georgia Tech’s online master’s programs, Grand Canyon University, University of Illinois (iMBA), University of Maryland Global Campus, Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU), Strayer University, and Western Governors University). School and program positioning remains conventional. School homepages make no mention of AI. None of the ten schools make any prominent AI claims, let alone tout a next generation AI tutor.

There are two (partial) exceptions:

- Grand Canyon University put out a news story highlighting two AI teaching assistants (“Mira” in science and healthcare, and “Isaac” in math). Both are depicted as humans, but interactions appear to be text-only (i.e., not audio and video-enabled avatars).

- More ambitious is the University of Illinois. The low-cost iMBA program is building a “customized avatar to look and talk like a live professor.”

Slow progress is not surprising: alignment of text, audio, and video is much more complex than text alone. Extensive testing is essential to clarify the avatar’s contributions and limitations, and when it supplements or replaces (human) faculty. Indeed, campus politics, not technology, may be the more formidable barrier.

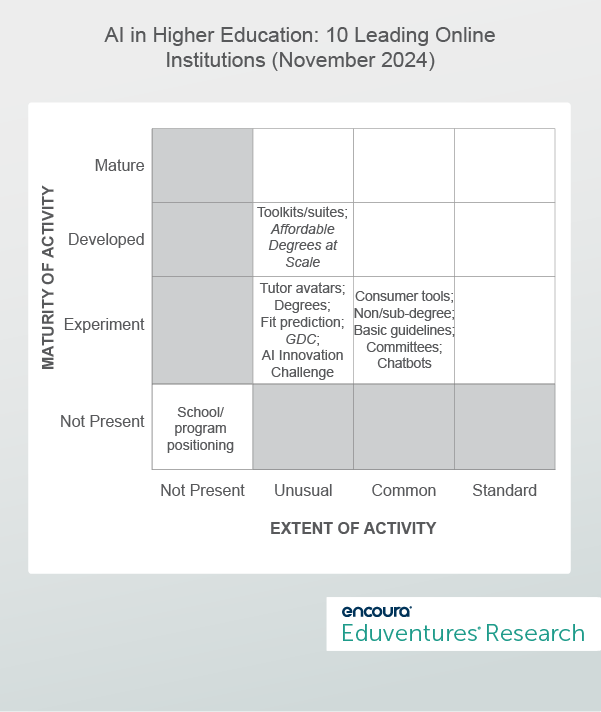

It’s still early days for next-generation avatars, but the 10 leading online schools show evidence of other AI activity. Figure 1 displays a variety of AI efforts by extent and maturity.

The most common types of AI activity across the 10 leading online schools are facilitated student access to consumer AI tools (e.g., ChatGPT)—beyond pervasive use by students on their own courses/concentrations/certificates about AI, AI use guidelines, AI committees, and text-only chatbots. Such activity is judged experimental at most schools.

Atypical activity, aside from tutor avatars, spans degree programs about AI, predictive admissions tools (Georgia Tech), and AI consortia (SNHU’s new Global Data Consortium, co-hosted by the American Council on Education). ASU’s partnership with OpenAI, which is fueling a new AI Innovation Challenge for faculty and staff, is also exceptional.

The only “Unusual” activities judged “Developed” rather than experimental are ASU’s A.I. Teaching and Learning Resources page and Georgia Tech’s Affordable Degrees at Scale event, now in its 10th year, where AI is central to the agenda.

Leading online schools are not ready to trumpet AI—and tutor avatars do not appear imminent—but there is plenty of work behind-the-scenes. The next few years will reveal what is realistic and useful.

Prediction 2: Short-Term Pell will pass.

Well, it did not pass.

The latest bills (H.R.6585 - Bipartisan Workforce Pell Act and H.R.793 - JOBS Act of 2023, as well as a similar Senate bill) did not make it out of committee. Tensions over program eligibility and the role of for-profit and online schools, plus questionable outcomes for many graduates, hampered negotiations.

Bills also got tangled in tangential battles. Language inserted that sought to bar the wealthiest universities from federal aid or force them to cover forgiven student loans—to help pay for expanded Pell—attracted concerted lobbying.

Attempts to tuck “Short-Term Pell” into the annual National Defense Authorization Act have stalled.

Other higher ed issues held congressional attention in 2024: FAFSA screw-ups, fights over loan forgiveness, and hearings on alleged antisemitism at elite universities crowded out Pell expansion.

A second Trump presidency might favor non-degree programs:

- Expect to see the return of the Industry-Recognized Apprenticeship Program (IRAP), a first-term Trump effort to expand and diversify apprenticeships as a college alternative. The Biden administration nixed the change.

- Trump’s touted “American Academy,” a free national online university (again, notionally paid for by taxing elite colleges), leads with access and affordability. Bachelor’s degrees are the focus, but adding non-degree programming would play well. Online is a poor fit for hands-on non-degree programs, but academy courses could be combined with offline training or work experience. Of course, the theoretical academy has many conceptual and logistical hurdles to clear.

If Trump made good on his (far-fetched) promise to eliminate the U.S. Department of Education, returning education to the states (along with some federal dollars), non-degree efforts might receive a boost in states that have already made associated investments (e.g., Iowa, Maryland, and Virginia).

A fan of for-profit higher education, Trump might push for short-term Pell expansion, while also (as he did in his first term) rolling back revived federal Gainful Employment rules that target lower division (i.e., non-degree) for-profit schools and programs. But the Republican-backed College Cost Reduction Act (CCRA) doubles down on regulation of program-level outcomes, raising the stakes by proposing extra funding for high performers and student loan repayment liability for laggards. Many non-degree programs score below-average on the early career earnings the CCRA focuses on.

One thing is clear: there are a lot of unknowns. The next four years could produce a game-changing realignment of higher education in favor of non-degree programming. But recent non-degree momentum is not simply a matter of who is in the White House. Deeper forces (e.g., aging society, labor shortfalls, skills deficits) are at play. Institutions of all kinds should continue to think about their most strategic degree/non-degree mixes.

Prediction 3: In a new bachelor’s era, program strategy shifts from variety to focus.

My final 2024 prediction concerned programmatic focus among master’s and baccalaureate institutions. I argued that the trend of ever-more bachelor’s programs enrolling ever-fewer students is unsustainable and non-strategic. These institutions—among the most challenged in today’s market—would be better off devoting limited resources to fewer programs.

I predicted three things:

- The total number of bachelor’s programs offered by master’s and baccalaureate schools will fall for the first time since IPEDS began tracking program numbers in 2012.

- The average number of main fields of study offered by these schools at the bachelor’s level will also fall for the first time.

- The share of bachelor’s conferrals at these schools, held by their five largest bachelor’s programs, will grow for the second year in a row, reversing the long-term trend.

Was I right? Yes, on all three counts.

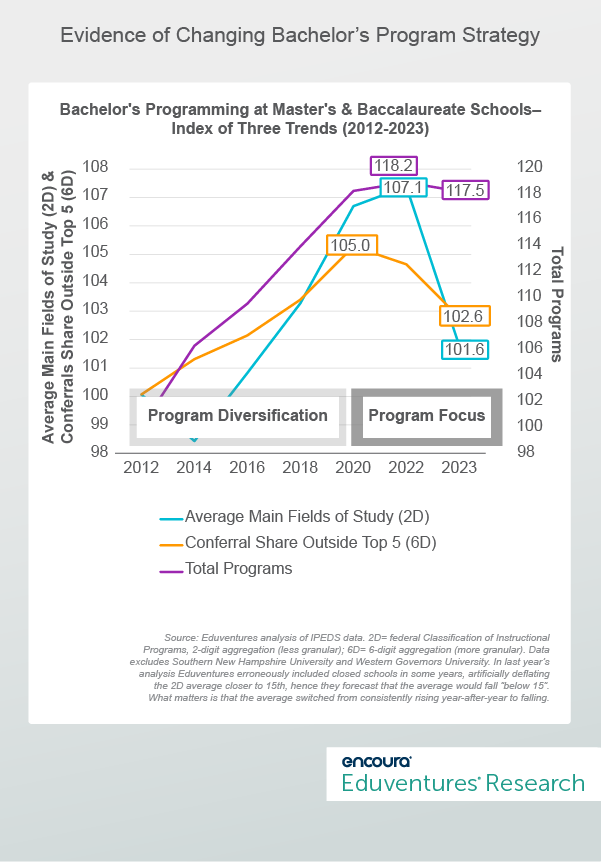

For the first time since IPEDS began tracking program volume in 2012, the total number of bachelor’s programs reported by master’s and baccalaureate schools fell according to the latest data (for academic year 2023): down 0.6% after climbing 18% between 2012 and 2022.

This is not a big shift in absolute terms but is a striking change of direction.

Similarly, as predicted, the average number of main fields of study offered by these institutions at the bachelor’s level declined for the first time in at least a decade, down 5% to 16.7.

Third, greater programmatic concentration is also visible in the proportion of bachelor’s conferrals held by the largest five programs: increasing for the second year in a row (after years of decline) to 48.9%.

Given different scales, Figure 2 displays the three trends as indices. (The chart inverts the third trend—to show the share of bachelor’s conferrals outside the top five programs—so the trajectories of all three trends are consistent).

We are in a new era of program focus over diversification, visible across all institution types, not only those in the master’s and baccalaureate categories. This is strategic when prospect pools are shrinking, consumer and policy skepticism are high, and bachelor’s alternatives are growing.

The irony is that total bachelor’s programs offered by master’s and baccalaureate institutions continued to rise through 2022 even though the number of such schools declined over the past decade. Remarkably, it took until 2023 for both the institutional and program totals to fall in the same year.

My forecast is that the three trend lines in Figure 2 will continue to fall until at least 2030, bringing supply and demand into better alignment.

Look out for my predictions for 2025 in early January.

Identify new program opportunities—at the undergraduate or graduate level—to expand market reach and drive enrollment growth.