As is my annual tradition to start the new year, I am unveiling my predictions for the year ahead in higher education. Let us dive into the first two today, with the third to follow next week.

For 2025, I predict:

- For the first time, the number of fully online undergraduates will surpass those enrolled in no online classes.

- The U.S. Department of Education will become collateral damage amid the second Trump administration’s quest for government efficiencies.

Am I right? Am I crazy? Read on to see what you think.

Prediction 1: The number of fully online undergraduates will surpass the “campus-only” cohort for the first time.

Online enrollment is more significant than you think. The modality continues to show strong momentum post-pandemic and is helping many types of institutions manage a rocky recruitment and operational environment.

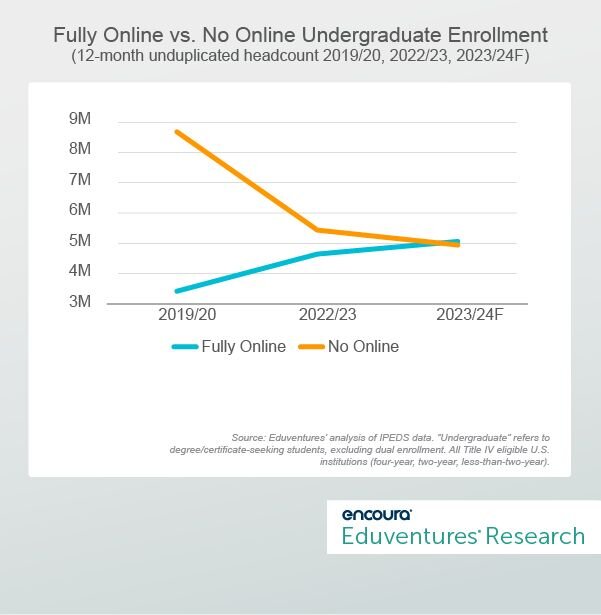

The most recent “official” enrollment data (from IPEDS) is for fall 2022, barely out of the pandemic during which most students were forced to study at a distance. A better gauge is the new 12-month unduplicated headcount data for 2022/23, also from IPEDS. Not only is this data more recent, but it also captures year-round enrollment (which reveals the true scale of online).

Figure 1 charts undergraduate enrollment growth by modality between 2019/20 (the pre-pandemic baseline) and 2022/23.

Figure 1.

Total undergraduate enrollment slipped 6% but fully online leapt by more than a third. The number of students enrolled in no online courses slumped by 37%.

Fully online undergraduates made up 27% of all undergraduates in 2022/23, nearly a fifth higher than the fall ratio (23%). The gap is bigger still for undergraduates who take some courses online: 33% of undergraduates fell into this category as of fall 2022, but the ratio was 42% over the 12-month period of 2022/23.

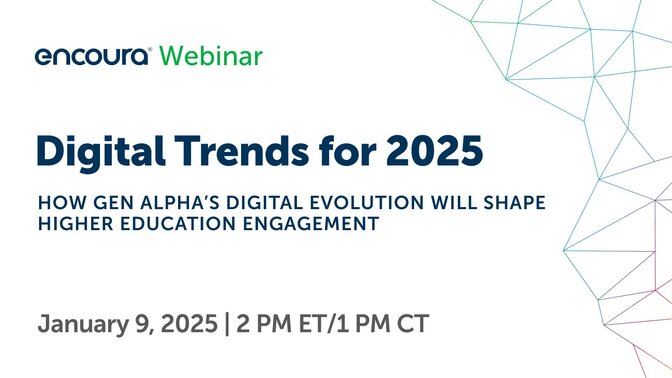

I predict—Figure 2—that a milestone will be reached in 2025, when the enrollment data for 2023/24 is published: for the first time the number of fully online undergraduates will exceed the number of undergraduates enrolled in no online classes.

Figure 2.

This trend is not confined to large online universities. Even medium and small master’s-level institutions and baccalaureate colleges outside the elite show the same pattern. Together these schools posted a 10% growth in fully online undergraduates, constituting over a fifth of all undergraduates in 2022/23. Some 45% of undergraduates took at least one online class, a 10-percentage point increase in four years. The “no online” cohort shrank by 38%. It will take a few more years for fully online enrollment to surpass “no online” at these schools, but the underlying trend is there.

Online courses and programs enable schools of all types to diversify enrollment, increase capacity, and rethink instructional and organizational norms. Such innovation is critical: the smaller master’s and non-elite baccalaureate cohort saw total undergraduate enrollment drop by 11% between 2019/20 and 2022/23.

But online momentum also means risk and uncertainty. A growing “distance” between students and institutions may undermine loyalty and foster a transactional mindset. Schools must invest in instructional design and faculty development to transcend experientially-limited online courses. Next generation AI-enabled online learning may undermine student agency and shrink traditional faculty roles, or that is the risk if higher education leaders do not think things through.

Online learning is changing undergraduate education at scale, and we are only beginning to understand the implications.

Prediction 2: U.S. Department of Education will become collateral damage in the first year of Trump’s presidency.

Promising to abolish the U.S. Department of Education has been an on-off feature of Republican manifestos since the first Reagan administration. Established as a federal agency after the Civil War and later as a component of the Health & Human Services Department, “Education” became a dedicated department and cabinet-level position in 1980 under President Carter.

Critics charged federal overreach, citing the absence of a constitutional mandate for a federal role in education. On the campaign trail, President-elect Trump vowed to eliminate the department, alleging ideological capture, frivolous spending, and powers that should be returned to the states.

Project 2025, a Heritage foundation-coordinated policy blueprint for a second Trump term is unapologetic that the Department must be wound up and its functions redistributed. A new Trump-backed agency, the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) headed by Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, billionaires eager to scythe through the federal bureaucracy, is looking for targets.

I predict that the U.S. Department of Education will be a casualty of reform and cost-cutting efforts in 2025.

Not because it is especially large: the Department’s budget ranks in the middle of the pack, and its headcount is the smallest of the fifteen executive departments.

Not because much of the department’s budget will actually be cut: most funds flow to states, school districts, institutions, and students, and support routine, non-controversial things (e.g., Pell Grants, pre-school expansion, special education, data collection).

The U.S. Department of Education is vulnerable for other reasons.

First, because it is tangled in the culture wars, notably DEI battles (e.g., allegations of use of “Critical Race Theory” in K-12 classrooms, required “equity” plans tied to special education funds during the pandemic, and controversies over Title IX and transgender athletes). The General Counsel of the Department signed the Biden Administration’s amicus brief favoring affirmative action in college admissions that the Supreme Court then banned.

Colleges are at the epicenter of heated debates over free speech and “cancel culture.” Congress grilled Ivy League presidents over alleged antisemitism on campus and mishandling of campus protests amid the Gaza conflict. These hot-button issues may not involve the Department directly but are portrayed as liberal ideology gone awry on the Department’s watch.

Second, recent events undermined perceptions of departmental competence. The FAFSA debacle invites accusations of mismanagement, giving ammunition to the cost-cutters. The Department is associated with President Biden’s politically-charged (and very expensive) efforts to accelerate student debt forgiveness, which were mired in legal challenges until the Department formally ended forgiveness efforts on January 3, 2025.

Third, the Department lacks an ambitious raison d’être. Officials have retreated from big centralizing efforts like Common Core and No Child Left Behind, the sort of thing that helps justify a federal department. Most of the Department’s Biden-era program integrity reforms, spanning state authorization, accreditation, third-party servicers and online program management, ran into the sand, and have now been withdrawn, along with high-profile policies on transgender athletes and student loan forgiveness. It is easy for critics to blame the Department for flagging K-12 student performance and low college graduation rates. Paradoxically, the Department can be criticized for federal overreach and the absence of big policy wins.

Axing the Department could be a symbolic win for the new administration, and within the realms of possibility now that both houses have Republican majorities. Other departments will yield more savings but might face stiffer resistance and be harder to caricature. Merging “Education” with the Department of Labor, say, could be presented as both cost rationalization and sensible integration of education and employment policy. A significant portion of federal student loans might be reprivatized, in tune with caps on student borrowing and rolling back debt relief programs (see Prediction 1), all of which would shrink the federal education remit.

The nominated Secretary of Education, Linda McMahon, favors expansion of K-12 voucher programs, another way to decentralize federal funding.

Once unthinkable, the unravelling of the U.S. Department of Education has never been more likely, and I predict it will advance significantly in 2025. It's not really about cost savings; for proponents, this will be a symbolic victory emblematic of an ideological turn.

Of course, while almost no one working in higher education today lived it, the two most important pieces of post-war higher education legislation (the GI Bill and the Higher Education Act) were enacted without a stand-alone Education Department, as were the original Pell Grants.

What are the implications for colleges? Flagship programs like Pell Grants and federal student loans are not going anywhere, so day-to-day operations are unlikely to be disrupted. The deeper implication—which will take years to fully appreciate—is the prospect of diminished standing and influence for education at the federal level.

Stay tuned next week for my third higher ed prediction for 2025!