“Do you want fries with that?” This has long been the signature joke to poke fun at the career development and opportunities—or perceived lack thereof—of humanities and social science majors. While it’s true that these students don’t have career paths readily laid out for them, studies show that

Does this mean that these types of students keep the career development office busier than others? Conversely, do STEM majors require fewer services? Data from the 2019 Prospective Student Survey™ provides a better understanding of the connection between intended major and student expectations for career development services.

The Baseline

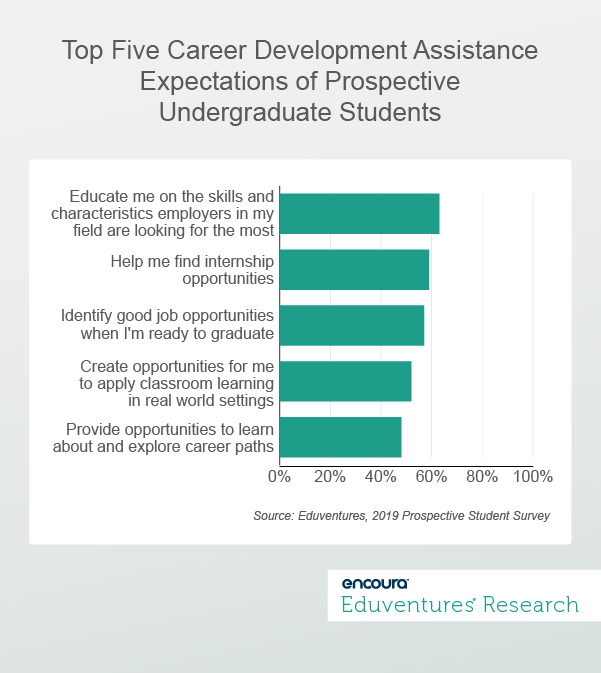

Before we dive into differences among different majors, let’s first look at student expectations on average. Figure 1 illustrates the top five expectations for institutional assistance in student career development nationally.

Not surprisingly, many students want assistance finding internships (59%) or jobs (57%). More interestingly, two of the top five student expectations revolve around the classroom experience: 63% of students want to learn skills and characteristics employers in their chosen fields are looking for, and 52% would like opportunities to apply classroom learning in real world settings.

This finding would seem to put faculty on the task, rather than the career services office alone, and echoes the increasingly pragmatic approach that students and their families take when investing in higher education. A shift like this—to placing the responsibility of formalized career services (at least partially) in academic departments—could pose challenges for many schools, both operationally and culturally.

Let’s now review how student academic interests shape their expectations for career development.

Not all STEM is Created Equally

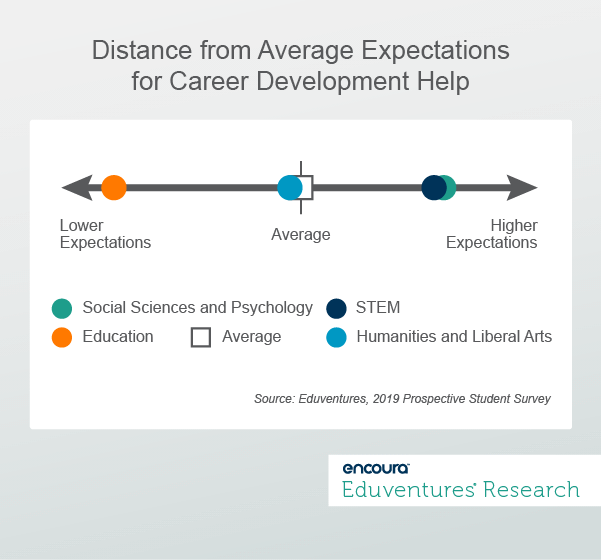

Which types of students have higher or lower expectations for career planning help from their colleges and universities? Figure 2 shows the standardized distance from the average (midpoint) for some of the most popular academic areas.

This shows that students who are interested in studying education have fewer expectations for career help from their schools than the average student. In contrast, students interested in STEM programs as well as social sciences and psychology expect a very similar level of career help, which is higher than the average.

At first glance, it seems that students who are interested in fields known for excellent job opportunities have similar expectations for institutional career help as students interested in fields with less articulated career paths. Taking a closer look at the STEM prospects, however, we see differences between STEM students—for instance, those who want to study engineering and those interested in computer science.

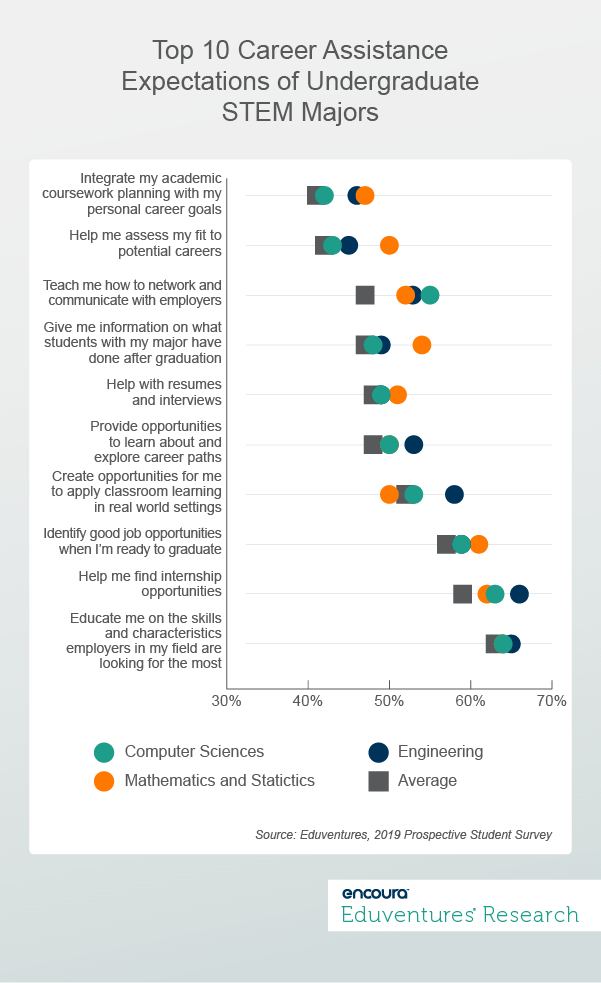

Figure 3 shows the top 10 career assistance expectations of undergraduate STEM majors in the aggregate, and broken out by those interested in studying computer science, mathematics and statistics, and engineering, respectively.

The variance in expectations for individual STEM program areas illustrates that not all prospective STEM students are created equal. We see, for instance, that the expectations of aspiring computer science majors are closer to the average for all students—with the exception of expectations around being taught how to network and communicate with employers (55% vs. 47% average) and, to some extent, being provided with internship opportunities (63% vs. 59% average).

In contrast, those interested in mathematics and statistics are expecting guidance on potential career paths more than other students, including students interested in other STEM programs. Fifty-four percent would like information on what graduates in their prospective majors have done, compared to 47% of all students, and would also like help in assessing their fit with potential careers (50% vs. 42% average).

These data points emphasize that fulfilling the career development promise to students entails more than simply sending them to the career services office for a crash course on resume building or internship placements. Students choose their majors with perceptions around career entry in mind, and expect their schools to help them figure out how to navigate their perceived pathways.

Additionally, these pathways can vary significantly by major. Students who choose programs with strongly-articulated career paths in booming industries, such as computer science, may be satisfied with help in securing their first jobs, while others in less articulated majors—like mathematics and statistics— expect to receive assistance in imagining what their path may look like.

The Bottom Line

Many students enter college with hopes and dreams for their future careers, and increasingly expect their schools to not only educate them but also ensure their employability. Limited resources often impede the ability of schools to provide formalized career services tailored to individual student needs. But, applying a “one-size-fits-all” approach to career services across all program areas may satisfy some, while leaving others feeling underprepared and disillusioned.

Addressing expectations on a programmatic, or at least departmental, level may offer a greater degree of personalization of these services. It may also provide institutions with a framework for prioritizing the investment of their limited career development resources, offering more support to students who arrive expecting more, while conserving resources where expectations for support are lower.

Thursday, October 24, 2019 at 2PM ET/1PM CT

- How do prospective adult learners make decisions regarding their educational futures?

- How can institutions and service providers better understand and anticipate the behaviors of prospective adult learners?

Thank you for subscribing!

Thank you for subscribing!