Every admissions cycle, national headlines underscore a critical problem for colleges: “College is unaffordable!” and “Students question the value of a college education!” These two concerns—affordability and value—are true to different degrees for different kinds of students.

But how do institutions make the distinction between the problem of value vs. the problem of affordability? They are certainly related, but as our data shows, also distinct. Understanding the underlying dynamic can help colleges identify and support students facing financial barriers.

Affordability and value reflect two different perspectives of the value equation of higher education. When it comes to college choice, they are in constant tension.

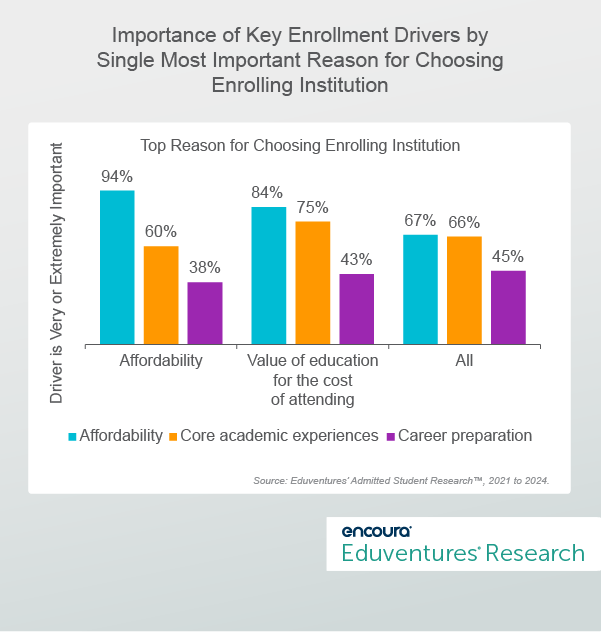

Figure 1 shows this tension. It compares the importance of the three most critical components of the value equation—affordability (price), value for the cost, and core academic experiences (benefit)—segmented by the single reason that students said they ultimately chose their schools.

Figure 1.

This shows that students who single out value believe that the benefit side of the equation—academic quality and career preparation—is nearly as important as the price side of the equation (75% academics and 43% career preparation, i.e., “benefit,” and 84% affordability, i.e., “price”). Students who single out affordability believe that the price side of the equation is far more important (94%) than the benefit side (60% academics and 38% career preparation).

While institutions may be tempted to use the same strategies to reach both types of students, that would be a mistake. Students who single out value are price-conscious; students who single out affordability are price-bound.

What else does our data tell us?

1. Affordability is a bigger driver than value.

Post-COVID, a quarter of admitted students surveyed by Eduventures explicitly listed affordability or value as the single most important reason they chose to attend their schools (leaving 75% to specify another reason). But this quarter contains many students for whom access is not guaranteed, like those from low-income families or those who would be the first in their families to attend college.

In a fit of wishful thinking, some schools might like to believe that admitted students are more influenced by value than they are by affordability. Thus, if the institution could articulate its value more effectively through more relevant messaging about the benefits of its education, it would tip the balance to convince students it is worth the price.

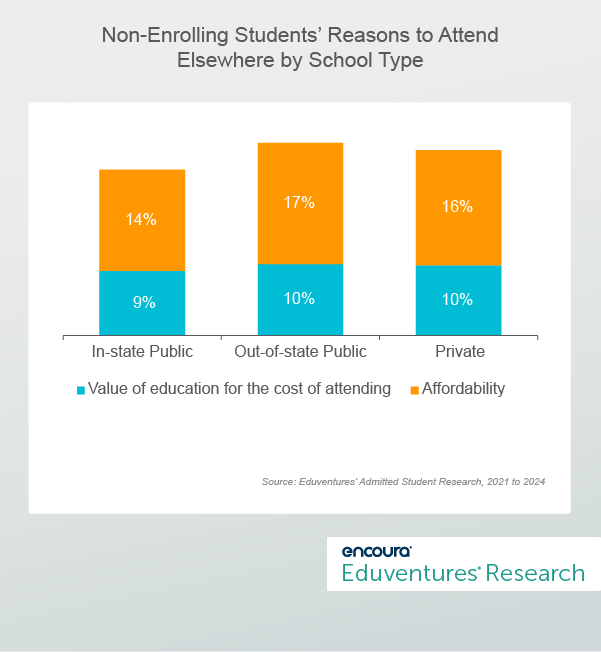

But Figure 2 shows that the reverse is true. It shows the percentage of non-enrolling students going elsewhere due to affordability or value for three types of admitting institutions.

Figure 2.

For every type of institution, more non-enrolling students chose another school due to affordability rather than value. In-state public institutions lost 14% of their students to pure

affordability (9%), while out-of-state public and private institutions lost only slightly more (16%-17% affordability vs. 10% value).

Questions of value and affordability are consistent and universal. For students whose primary concern is affordability, messaging value will help, but it won’t solve an institution’s access problem.

2. Both affordability and value drive students to lower net-price institutions.

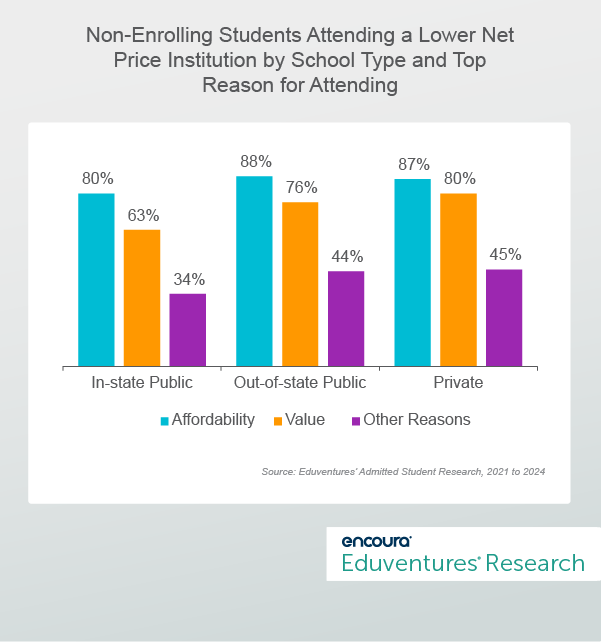

Student enrollment decisions often hinge on comparing the net price of the chosen institution with that of the one they declined. Their actions show their level of price sensitivity. Figure 3 shows the percentage of non-enrolling students who chose to attend a lower net price institution, segmented by the type of institution they are attending, and the top reason they chose it.

Figure 3.

This shows that almost all non-enrolling students who single out affordability as their reason for enrollment attend a lower net price institution, regardless of institution type. But students who single out value are also highly likely to choose a lower net price option.

For example, 80% of non-enrolling affordability-driven students attending in-state public institutions chose a lower net price institution while nearly two-thirds (63%) of value-driven students also chose a lower net price institution. For students attending private institutions, this low net price choice is nearly equal between affordability-driven (87%) and value-driven students (80%).

Can one strategy alone address the similar outcomes in these two decision segments?

3. Those who decide based on affordability are fundamentally different than those who decide based on value.

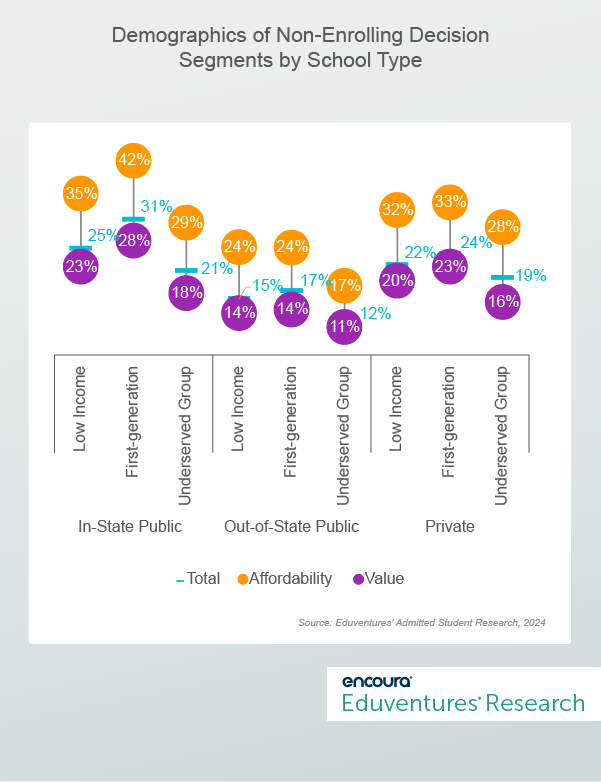

Value- and affordability-driven students are substantially different demographically. Figure 4 shows the average demographic profile as well as the profile within each decision segment by the type of admitting institution.

Figure 4.

Figure 4 shows that in every institutional context, non-enrolling students who single out affordability are much more likely to be a member of an access group compared to all non-enrolling students. Conversely, non-enrolling students who single out value are slightly less likely to be a member of an access group. The twin conversations of value and affordability hit students differently. And the affordability conversation is most critical for students in access populations.

The Bottom Line

There are students out there who are seeking a great education at a great price, but more and more students primarily need the great price. Can an institution turn an affordability problem into a value solution? Maybe, but only by thinking creatively and expansively about affordability. Here are some strategies to start:

- Develop lower-priced options. Institutions don’t necessarily need a wholesale tuition reset. But lower-cost, shorter time-to-degree, try-before-you-buy, or non-degree options can expand opportunities for very cost-sensitive students.

- Strategic financial aid should reach the students who need it the most. Review your financial aid packages targeted to families in different income brackets to assess whether you are meeting the needs of lower- or middle-income families.

- Some students need ongoing financial support to thrive in college. Affordability sensitive students will not only struggle to enroll in school, but they will also struggle financially while enrolled in school. What more can your institution do to provide ongoing financial support and counseling for these students beyond the standard financial aid package?

- Manageable debt is okay, unmanageable debt is not. Students have anticipatory fears of student debt curtailing their futures. Commit to manageable debt loads for students, showing students how they will be able to manage debt. Make their debt manageable by guaranteeing outcomes or buying back debt. Explore what manageable debt means for students from loan averse lower-income families.

- Message value but recognize that it won’t tip the balance for the set of students who are strongly affected by affordability. Demonstrate that your institution is prepared to be a long-term partner in helping its students find success. This is the ultimate outcome of an education built on a strong scaffolding of affordability.

Identify the top factors that truly influence transfer students in college search and the best digital strategies to engage them.