Welcome to Part 2 of our 2025 higher ed predictions! Last week, we kicked off the year by predicting that fully online undergraduates will surpass campus-only enrollment for the first time, and that a second Trump administration will shake up the Department of Education.

Today, we dive into my third and final prediction for the year ahead: the elimination of Grad PLUS loans and the implications for schools and student debt.

Do you agree with these predictions? Read on to get my take.

Prediction #3: Grad PLUS loans will be eliminated, and schools will be on the hook for unpaid student debt.

For over a decade, the federal government has tried to regulate under-performing degree programs, aiming to steer students (and federal dollars) away from programs that do not lead to well-paying jobs and saddle graduates with excessive debt.

But partisan ping-pong meant such rules were never implemented. “Gainful Employment” regulations (focused on for-profit institutions) were conceived under Obama, rescinded under Trump, and revived and expanded under Biden (but have yet to come into force).

Will Trump 2 mean another rescinding? I don’t think so. In fact, I predict that more exacting rules will be agreed to in 2025.

The College Cost Reduction Act (CCRA), a bill sponsored by Rep. Virginia Foxx (outgoing Chairwoman of the House Committee on Education and the Workforce), and the best guide to what to expect, envisages major changes:

- All students included. The bill is committed to Gainful Employment-style program-level monitoring with the addition that non-completers are included (risking lower median earnings and higher debt non-payment).

- No more PLUS loans. Higher interest Grad and Parent PLUS loans—that allow graduate students and parents (of undergraduate students) to borrow up to the cost of attendance (minus other aid) once other federal loan limits are reached—would be eliminated.

- Risk & reward passed on to schools. Colleges would have to reimburse a portion of unpaid student loans, while schools that outperform would get extra funds.

If enacted, CCRA-style rules would have big implications for all programs eligible for federal student aid, but I want to focus on graduate programs.

Graduate students are a minority of borrowers but make up half of total federal student loan debt. Today, graduate students may borrow (using federal loans) up to $20,500 a year, in line with average graduate tuition and fees. Additional borrowing is available through Grad PLUS loans, which were introduced in 2007.

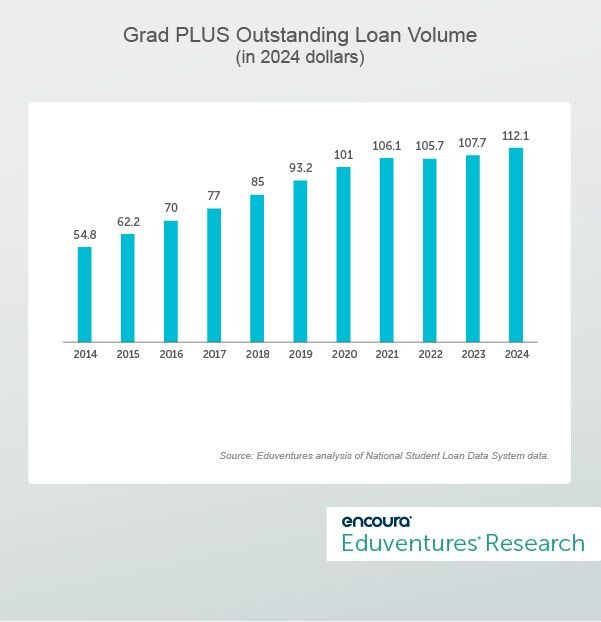

Grad PLUS borrowing is significant: 1.8 million current and former students had $112 billion outstanding in 2024, up from one million individuals in 2016. Figure 1 tracks the Grad PLUS portfolio in constant dollars over the past decade.

Figure 1.

Total outstanding Grad PLUS loan volume doubled in a decade compared to only 7% growth in graduate enrollment over the same period. This is why crafters of the CCRA think Grad PLUS has to go, arguing that it inflates graduate tuition and undermines return-on-investment (ROI) for students and taxpayers.

According to the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study, about 12% of graduate students take out a PLUS loan, but that underestimates the dollar significance. Grad PLUS loan volume is much smaller than that for mainstream Stafford loans ($900 billion outstanding), which combine undergraduate and graduate borrowers. But if half of this total is for graduate students, then Grad PLUS loans might constitute 20% of total graduate loan volume.

If Grad PLUS loans went away, more expensive graduate programs would see significant enrollment decline. CCRA advocates view cutting PLUS loans as an efficient way to curb tuition inflation and steer students to low-cost options. Rep. Foxx takes a dim view of loan forgiveness, vowing to reign in current schemes.

What are the implications for graduate programs of CCRA-style loan repayment provisions?

According to the CCRA database developed by backers of the bill, all colleges and universities would, for the most recent year with data, collectively owe $2.9 billion in unpaid student loans “fines.” That is 5% of total federal student loan volume for that year. Master’s and first professional programs are most likely to trigger the fee.

The penalty (all study levels) would be close to $100 million for one large for-profit school (University of Phoenix), and over $10 million each for about 30 institutions, including well-known public and private universities (e.g., Boston University, NYU, and Arizona State University) and some online giants (e.g., Southern New Hampshire University, and Liberty University). Over 600 institutions would be on the hook for at least one million dollars, and over 1,500 would own at least $100,000.

The data is broken out by program. At the master’s level, for example, 30 (four-digit) fields of study would be liable to return 10% or more of student loan volume. Examples include English, Fine Arts, Human Services, and Public Administration.

Under the CCRA, schools that outperform on affordability and outcomes would be eligible for a “Promise Grant.” The database notionally distributes $2.9 million in fines to over 1,000 institutions. Western Governors University, the low-price online giant, would garner $78 million in additional funding, and many affordable public institutions would each stand to gain tens of millions of dollars.

About 900 schools would earn more from the Promise Grant than forfeited in fines. But over 2,800 institutions would be worse off, including 83 that stand to lose at least $5 million.

The Bottom Line

The CCRA is not law yet (narrowly losing a House vote in December), but I predict that something like it has a good chance of passing in 2025. Colleges will lobby against it and some of the more radical elements may be removed. There will be loud objections to judging low earning but socially important fields in such stark terms. But with one-party control of congress, bi-partisan interest in sharpening college ROI, and college on the “wrong side” of a host of fervent cultural issues, 2025 may prove the year when program-level accountability finally happens and when the Grad PLUS crutch is kicked away.

The new metrics would be a financial boost for some schools, close to neutral for many, and a major headache for higher-priced schools and programs with middling outcomes.

If the CCRA passes, it may circumvent the need for negotiated rulemaking. “Gainful employment” rules rested on an interpretation of existing statute, not a dedicated law. The amount of detail in the current CCRA text suggests that lawmakers intend speedy implementation. The draft anticipates implementation as soon as 2026/27.

Well, that’s it for my three predictions for 2025. Sketching these possible scenarios helps us think through the importance of competing forces impacting higher education. Right or wrong, by year’s end, we will learn which forces triumphed and why. As always, I will evaluate my predictions come December. See here for my self-assessment of my 2024 predictions.

Eduventures Summit – higher education's premier thought leadership event – is returning to the Windy City next year. Secure your spot today!