Anyone following media coverage of faculty and student reactions to pandemic-induced online learning got the message loud and clear: NO THANK YOU. The effort was appreciated but returning to campus is priority #1.

The latest CHLOE (Changing Landscape of Online Education) report, a survey of online learning leaders in colleges and universities, offers a different perspective: more than a third of chief online officers (COOs) said that the remote pivot was “smooth and straightforward” and only 20% found it “very challenging.” Fully, 78% regarded the spring term as at least “largely successful.”

The pandemic is resurgent, giving lessons from the spring new urgency. Will 2020 be remembered as a painful hiatus best forgotten or as the engine of transformation? The answer is both, and CHLOE 5 findings are alive with this tension.

CHLOE’s Spring Pivot

Pre-pandemic, the CHLOE Survey, produced by Eduventures and Quality Matters, chronicled the policies and practices of online higher education in the United States. In March, when online learning was thrust from energetic sideshow to lead role, plans for the fifth CHLOE Survey went out the window. Efforts were turned instead to getting the chief online officers (COOs) take on the pivot to “remote instruction” and fall plans. The CHLOE 5 Survey ran in May and the report analyzes the views of 308 COOs from a wide spectrum of colleges and universities.

There is no dispute that online leaders, collaborating with administration, faculty, and staff, pulled off an amazing feat in the spring: facilitating remote versions of hundreds of thousands of courses for millions of students, often in just a week or two. As CHLOE 5 recounts, the average school had to convert 1,000 course sections and engage students and faculty, about half of whom had never learned or taught online.

In May, the pandemic appeared in retreat, but today is resurgent in much of the country. Most schools planned to re-open campuses for the new academic year, but trends may now favor another substantially or wholly remote semester.

For online learning advocates, the key question is this: mitigation or transformation? Many may see the job of online learning as simply managing campus disruption until COVID-19 passes, allowing “real” higher education to resume. Another view is that wrangling a pandemic will accelerate an online-centric higher education future in which pressing access, cost, and quality problems are humbled and schools embrace creative hybrids of in-person and online study. A third scenario is that 2020 will prove a cautionary tale underlining that online learning—by whatever name—is simply not fit, or at least not ready, to take center stage.

For online leaders quick to draw a distinction between emergency “remote instruction” and true online learning, the spring semester was a disorienting mix of heroism and amateurism. The potential of online learning to address perennial higher education challenges, such as access, cost, and quality, is beside the point in the grip of a crisis. But there is no denying that pandemic dislocation presents online learning with an opportunity to show what it can do.

What does CHLOE 5 tell us about spring realities and the trade-offs facing COOs in the fall and beyond?

Smooth and Straightforward?

In May, as the dust settled, chief online officers were rather pleased with how spring remote instruction turned out. Students were able to complete the semester, most faculty and students, inevitable stumbling blocks aside, appreciated the continuity, and online learning teams pulled off something unimaginable a few months earlier.

But timing, resources, and culture meant that, in reality, much of the burden of the spring remote pivot fell on individual faculty members: 61% of the CHLOE 5 sample said that “faculty took the lead in remote course design.” This may have been practical, but led to too many overwhelmed instructors and the uneven student experience widely noted in the media. Only 39% of schools worked within an institutional or departmental framework. “Smooth and straightforward” did not necessarily mean consistent and coordinated.

If spring “success” meant averting a complete shutdown and completing the year, the bar for fall is higher. One advantage back in the spring was that students had months on campus under their belts and knew their instructors. If many schools must rely at least in part on remote instruction in the fall, many classes may begin remotely, not to mention hosting brand new freshmen. Unlike the spring emergency, colleges have had months to prepare. Calls for tuition reductions and refunds may grow louder if a remote fall is judged inadequate.

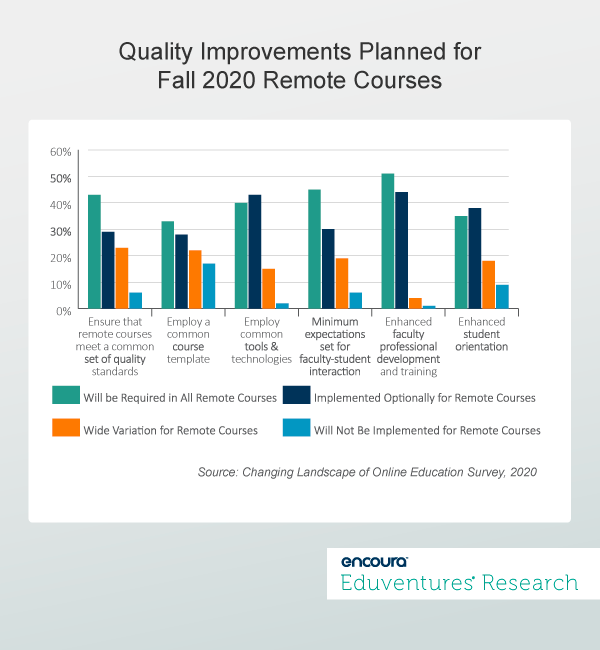

Figure 1 outlines improvements COOs planned for remote instruction, both accepting and challenging the decentralized norm.

Figure 1 makes clear that COOs see significant scope for improvement, but many are also culturally constrained. A slim majority of online leaders will “require” that all faculty participate in “enhanced” professional development, falling to 30-45% for common quality standards, course templates, tools and technologies, interaction expectations, and student orientation. Most schools will highlight good practice, but implementation will be optional or applied in parts of the institutions and not others.

The pandemic is driving substantive change in some schools but coming up against powerful norms elsewhere: mitigation and transformation.

Coordination is Not a Four-Letter Word

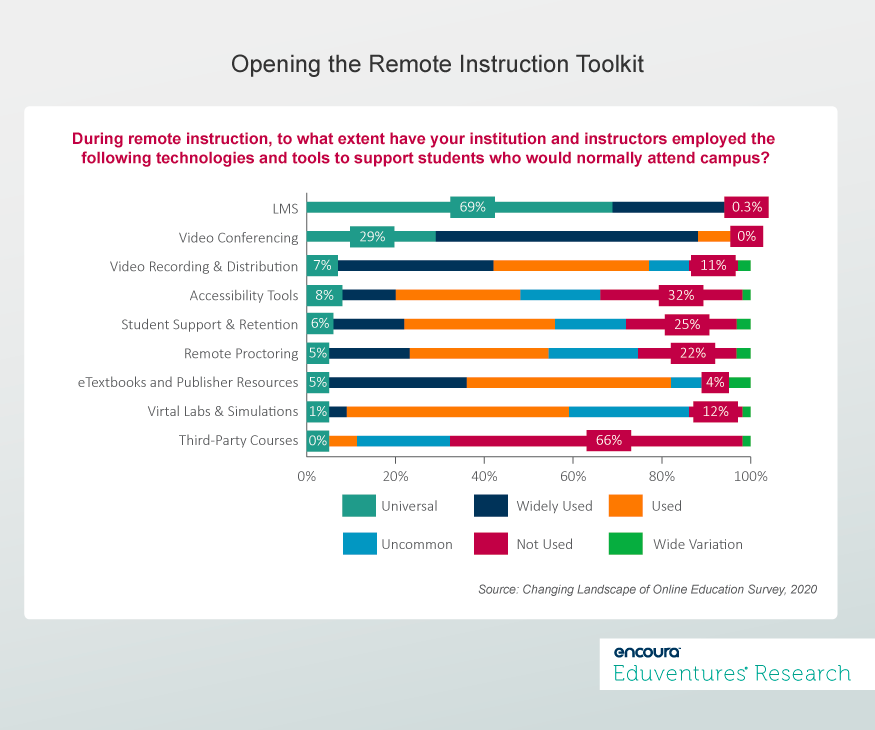

The remote learning toolkit available to institutions in the spring calls out a related issue (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

When asked which technologies and tools were used for spring remote instruction, the only mainstay was the learning management system (LMS). Many other applications were available and adopted, but practice varied widely within and between institutions. For most technologies, not even a double digit proportion of CHLOE 5 respondents said that adoption was universal.

In one sense, this is to be expected: students and course ranges inhibit one-size-fits-all solutions. But in another sense, the diffusion illustrated in Figure 2 is a reminder of how immature many technology segments remain in higher education. In most cases, schools did not and do not have a tried-and-tested technology toolkit aligned to their missions and pedagogies. Instead, they have a smorgasbord of solutions that facilitate creativity but hinder coherence, quality, and efficiency.

Lack of coordination drives up costs and compromises the student experience. Schools are spending more on an experience that students think is worth less.

An in-house mindset is also apparent from Figure 2. Despite the array of quality online courses typically produced by leading universities and available on platforms like Coursera and edX, many made available free, very few institutions took advantage.

Bottom Line

CHLOE 5 suggests the benefits of greater coordination. Schools that took a “strong institutional lead on technologies, course design, and pedagogy” for the spring remote pivot were more likely to say the semester proved “smooth and straightforward”: 46% vs. 32% for schools where faculty took the lead. Perceived success was also aligned: 33% of “strong institutional lead” schools judged the spring “very successful,” compared to only 18% where faculty operated largely independently.

Of course, coordination is not a silver bullet. Centralization efforts can misfire on substance and perception. The goal is often a balance of centralizing and decentralizing instincts and finding the right mix of campus and online elements for the schools, programs, or students in question.

The fundamental uncertainty of the pandemic’s trajectory, the apparent lull in cases in May, and relief as the spring semester hobbled over the finish line, may have persuaded most schools that sustained planning for a top-notch remote fall was unwarranted. Many schools may be regretting that now. The average COO has no doubt been busy planning for possible remote scenarios but may not always have had the full attention of the rest of the institution.

Even if the fall ends up resembling the spring, COOs sense that institutional assumptions—and budgets—will be severely shaken, creating space to do things differently in 2021 and beyond. COOs might be expected to take an optimistic view of the future of online learning, but it is also clear that many obstacles lie ahead.

Emergency remote instruction was hard; the cultural change needed to truly take advantage of online learning compounds the difficulty. Another semester of remote instruction, both better coordinated and more chaotic, will start to move the immovable.

Never Miss Your Wake-Up Call

Learn more about our team of expert research analysts here.

Eduventures Chief Research Officer at ACT | NRCCUA

Contact

Thursday, August 13, 2020 at 3PM ET/2PM CT

The annual CHLOE (Changing Landscape of Online Education) survey chronicles the evolution of online policies and practices in U.S. higher education, from the perspective of Chief Online Officers (COOs). The fifth CHLOE survey captures leadership reflections on the pandemic-induced emergency remote instruction in the spring: what happened, what worked, and implications for fall. The CHLOE 5 report is published amid a coronavirus spike that is persuading many colleges and universities to re-think their fall re-opening plans.

This webinar will distill lessons from the spring and, in conversation with a panel of online leaders, gauge early fall realities. Online infrastructure, experience and leadership played a pivotal role in enabling schools to see through the last academic year, but many leaders have been quick to draw a distinction between hastily assembled “remote instruction” and true online learning. As fall 2020 gets underway, and schools face a yet stiffer test, online leaders are stepping up once again. Robust, engaging, high quality remote learning, by whatever name and whether or not combined with a socially distanced campus, will define this one-of-a-kind semester.

Also in Program Innovation

Never Miss Your Wake-Up Call

Learn more about our team of expert research analysts here.