This has never happened before—the planned merger of Capella Education and Strayer Education, two of the largest for-profit higher education companies in the country, is the first of its kind. In the past, big for-profit schools have snapped up small ones, some large players have sold off divisions and brands, and this year two giants (Education Management Corporation and Kaplan) announced plans to sell to nonprofits. But the U.S. has never witnessed two big, for-profit schools become one company.

Is the merger a sign of strength or weakness for these companies and for-profit higher education? A bit of both.

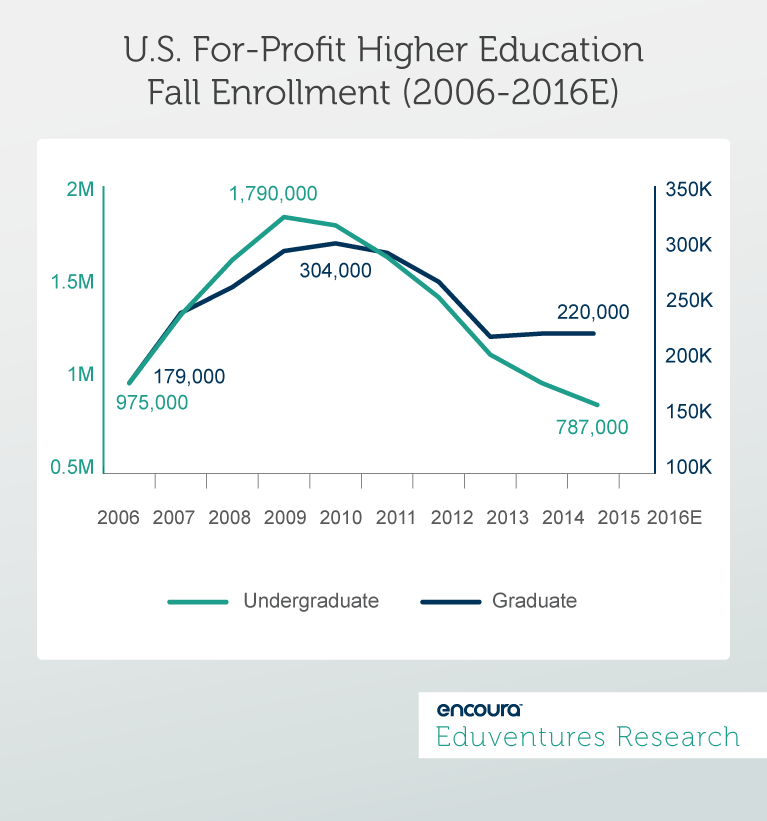

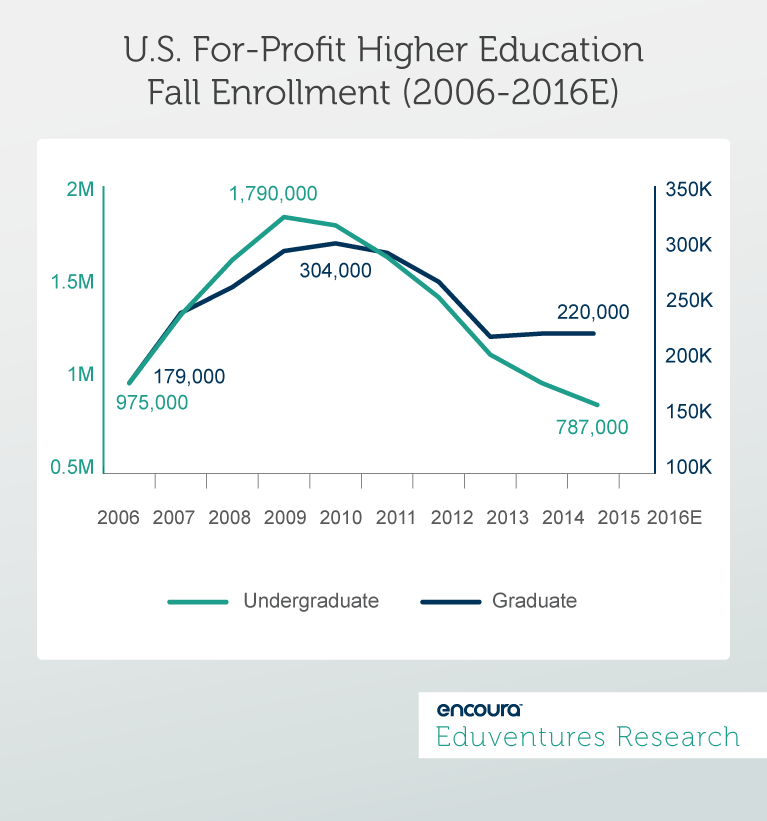

The backdrop to the merger is the rise and fall of for-profit higher education enrollment over the past decade (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Back to the Start

Source: Eduventures analysis of IPEDS and National Student Clearinghouse data- 2 and 4-year schools.

At the undergraduate level, for-profit enrollment grew 80% between 2006 and 2010, and more than 60% at the graduate level. The Great Recession, coupled with for-profit school emphasis on convenience and flexibility for working adults and hefty marketing budgets, propelled the sector forward. But as the economy recovered and nonprofit schools embraced online learning and adult-friendly programming en masse, the for-profits crashed back to earth. Regulatory scrutiny under Obama exposed serious shortcomings at some institutions and tarnished the for-profit school brand. For-profit undergraduate enrollment has tumbled well below the 2006 total. Today it accounts for less than 5% of the undergraduate market (compared to 10% in 2010). Graduate enrollment has stabilized at just under 8% of the market, but below the peak of 2011 when the sector enjoyed an over 10% share. Two major companies, Corinthian and ITT, and many smaller ones, have gone out of business. Most other firms are treading water at best. A trickle of for-profits have become nonprofits, concluding that in higher education the profit motive is more trouble than its worth. The best-known for-profit, University of Phoenix, hit over 500,000 students at its peak but today is less than a third of that size. Grand Canyon University continues to thrive, but its core strategy has been to build a winning traditional campus serving traditional-aged undergraduates, and let its larger online business bask in the reflected glow. A smart move but hardly ground-breaking. Indeed, Grand Canyon recently reiterated its desire to become nonprofit.