Drawing on Eduventures’ 20-plus years of experience helping universities develop, launch, and assess academic programs, the Program Spotlight Series of Wake-Up Calls calls attention to best practices in program development.

If you have loosely followed the legal education market, you’ve likely heard concerning tales of declining enrollments and underemployed or, even worse, unemployed law school graduates with exorbitant debt loads. If you followed this market more closely, the negative picture becomes more dire and complex: Over the past few years, the number of LSAT takers increased while applications to law schools dropped, leaving law school administrators guessing whether there is a silver lining on the horizon. Bar exam passage rates declined as law schools lowered admissions criteria, indicating a competitive race to recruit any willing student who meets the minimum admissions requirements. Some schools, like Whittier Law School, see themselves forced to close doors altogether. A glimmer of hope entered the horizon late last year when applications to law schools unexpectedly increased. While a recovering job market was among the list of potential factors, prospective students themselves often cited the Trump administration as a main motivator for their desire to pursue a legal degree. The “Trump bump” in law education was excitedly observed in the media. Has the tide finally changed? It’s too early to say whether the renewed interest is here to stay, but it seems unlikely. As of now, the number of applications is still below the level needed to financially sustain the typical law school. While the changing political climate created a momentum of bipartisan activism, prospective students might soon realize that contribution to their cause doesn’t need to come with a $140,000 price tag, the current average cost of a law degree. As for recent anecdotes about an improving labor market, Law School Transparency, a consumer advocacy group for the legal profession, suggests that improving employment rates among graduates can be attributed to the decreasing number of law school graduates rather than an increased demand by employers. While the jury may be out on the “Trump bump,” here are two trends in legal education that may have greater staying power.

If you have loosely followed the legal education market, you’ve likely heard concerning tales of declining enrollments and underemployed or, even worse, unemployed law school graduates with exorbitant debt loads. If you followed this market more closely, the negative picture becomes more dire and complex: Over the past few years, the number of LSAT takers increased while applications to law schools dropped, leaving law school administrators guessing whether there is a silver lining on the horizon. Bar exam passage rates declined as law schools lowered admissions criteria, indicating a competitive race to recruit any willing student who meets the minimum admissions requirements. Some schools, like Whittier Law School, see themselves forced to close doors altogether. A glimmer of hope entered the horizon late last year when applications to law schools unexpectedly increased. While a recovering job market was among the list of potential factors, prospective students themselves often cited the Trump administration as a main motivator for their desire to pursue a legal degree. The “Trump bump” in law education was excitedly observed in the media. Has the tide finally changed? It’s too early to say whether the renewed interest is here to stay, but it seems unlikely. As of now, the number of applications is still below the level needed to financially sustain the typical law school. While the changing political climate created a momentum of bipartisan activism, prospective students might soon realize that contribution to their cause doesn’t need to come with a $140,000 price tag, the current average cost of a law degree. As for recent anecdotes about an improving labor market, Law School Transparency, a consumer advocacy group for the legal profession, suggests that improving employment rates among graduates can be attributed to the decreasing number of law school graduates rather than an increased demand by employers. While the jury may be out on the “Trump bump,” here are two trends in legal education that may have greater staying power.

Trend #1: If the mountain will not come to the prophet, the prophet will go online.

Online delivery has become commonplace in higher education, but law schools have long been reluctant to adopt this format for their Juris Doctorate (J.D.) programs. Many legal educators believe that the Socratic method can’t be applied in a distance format. Many also assume that the quality of online education is inferior to that of face-to-face instruction. Likely following a similar rationale, the American Bar Association (ABA) currently limits the number of credits granted through online education to 15 and prevents institutions from offering online courses to first-year students in order to comply with accreditation standards. Accreditation, of course, is required in most states if graduates want to sit for the bar exam and, ultimately, practice law. In the past decade, several institutions have filed for variances from the ABA restrictions around online delivery. Among these, Mitchell Hamline School of Law was the first school to receive approval for a part-time J.D. program with substantial online instruction, and graduated the first cohort of this program this year. Not all applications for variance were ruled in favor of the applicant institution, however. The growing push for greater flexibility in the delivery of law programs has caused the ABA to consider loosening its restrictions around online education by doubling the number of online credits students can take and allowing first-year students to take online courses.Trend #2: The Juris Doctorate is not the alpha and omega of legal education.

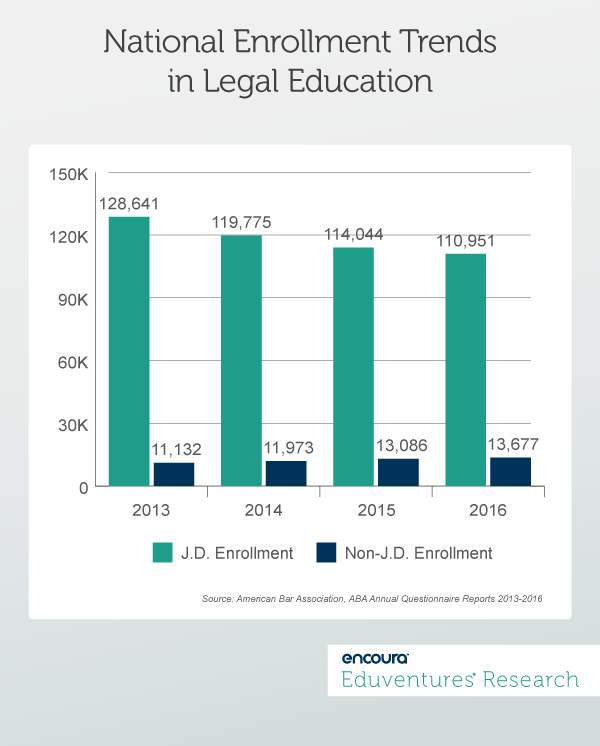

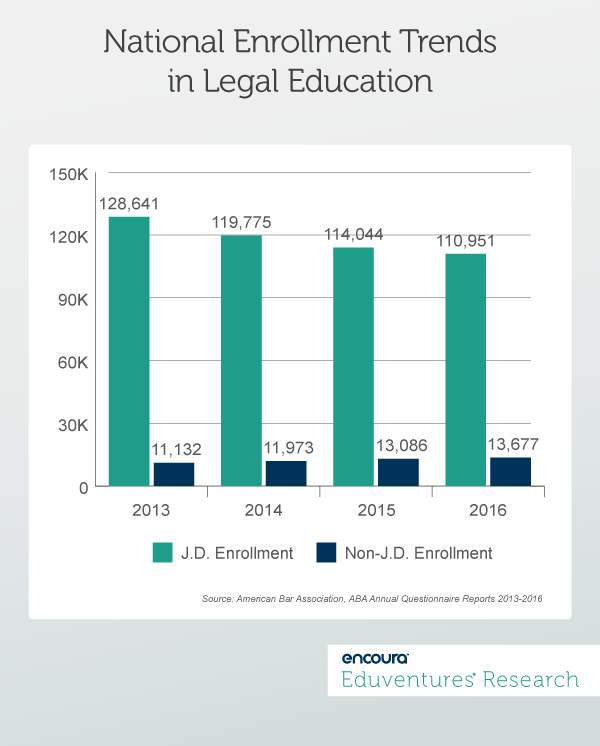

As enrollments in the traditional J.D. programs have steadily declined, some institutions have started embracing other, less traditional forms of legal education. The market for master’s programs in law, while still small, is gaining considerable traction. Figure 1 shows the decrease in J.D. program enrollment plotted against the increase in non-J.D. programs over a period of four years, as reported by ABA.

Figure 1.

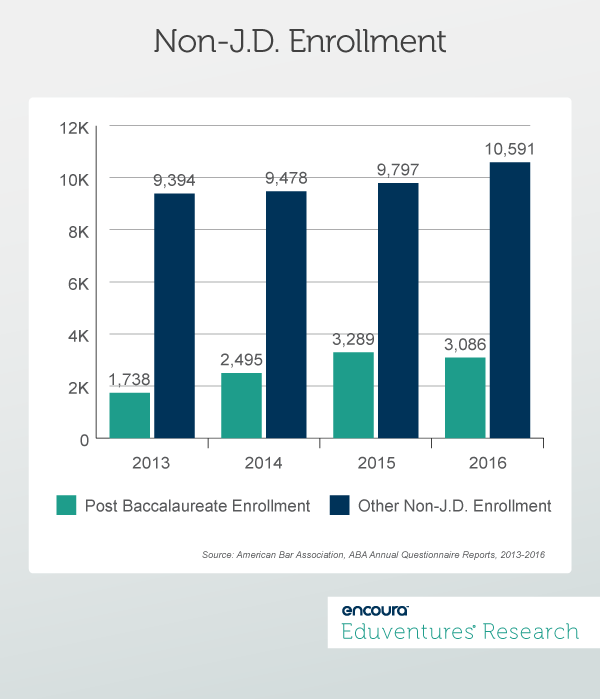

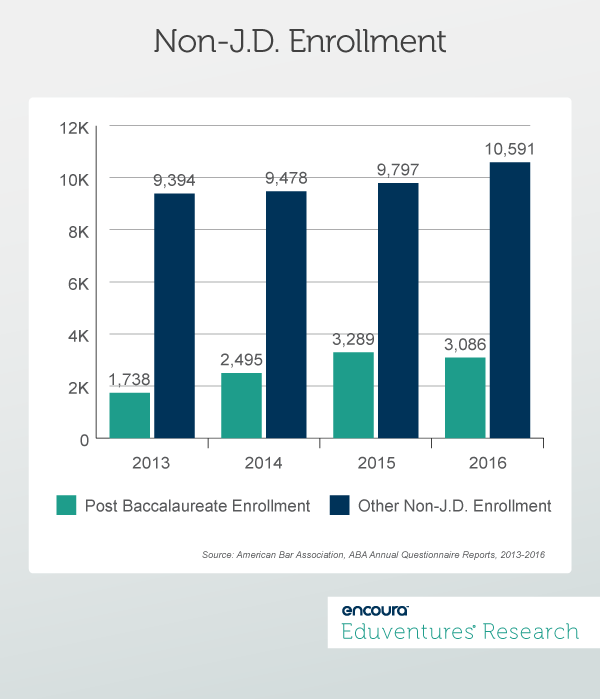

Non-J.D. enrollment includes Master of Laws (LL.M.) programs, which are typically geared toward international lawyers who plan to sit for a U.S. bar exam or domestic lawyers who wish to specialize in a particular area of law. It is interesting to note that much of this growth appears to be driven by what the ABA classifies as post-baccalaureate enrollment. This category, according to the ABA, includes master’s level programs that target non-lawyers. Figure 2 further breaks out the non-J.D. enrollment shown in Figure 1 and illustrates the recent growth in the post-baccalaureate programs compared to the growth of other non-J.D. programs aimed primarily at lawyers.

Figure 2.

The total enrollment in the post-baccalaureate programs is still relatively small, but it is hard to deny that some law schools have found innovative ways to expand their target audiences. These programs are typically geared toward professionals in accounting, finance, and healthcare who need to handle compliance issues. Are non-lawyers the new legal students?