“Colleges cash in on real estate” was a recent headline in Inside Higher Ed, describing how some institutions have sold property to generate cash flow. Enrollment challenges, inflation, and exhausted stimulus funds are driving sales, and property prices are at record levels coming out of the pandemic.

This is a trend to watch. In a world of online learning and remote working, when students and staff are spending less time on campus, evaluating campus assets may prove one of the most important strategic efforts for colleges and universities over the coming decade.

But should institutions be

Campus vs. Online

Most colleges are asset-rich: owners of land and buildings. Campuses cluster people, resources, and expertise and remain the heart and soul of most institutions but are expensive to operate. Campus remits— academics, facilities, and services—have only grown over time, pushing up costs.

For decades, low interest rates encouraged presidents to invest in new centers, dorms, and amenities, hoping to stand out from the crowd.

Yet even as campuses have expanded, enrollment shifted online, resulting in curious co-dependencies. To access a campus experience, students are spending more time off-campus. Online courses help traditional-aged students earn college credit in high school to save money, speed time to completion, and free up schedules for paid employment.

Fully online programs make it easier for adult learners and graduate students to combine work and study, widening access and making college more affordable. Most online students never come to campus, but schools use online tuition to subsidize the place.

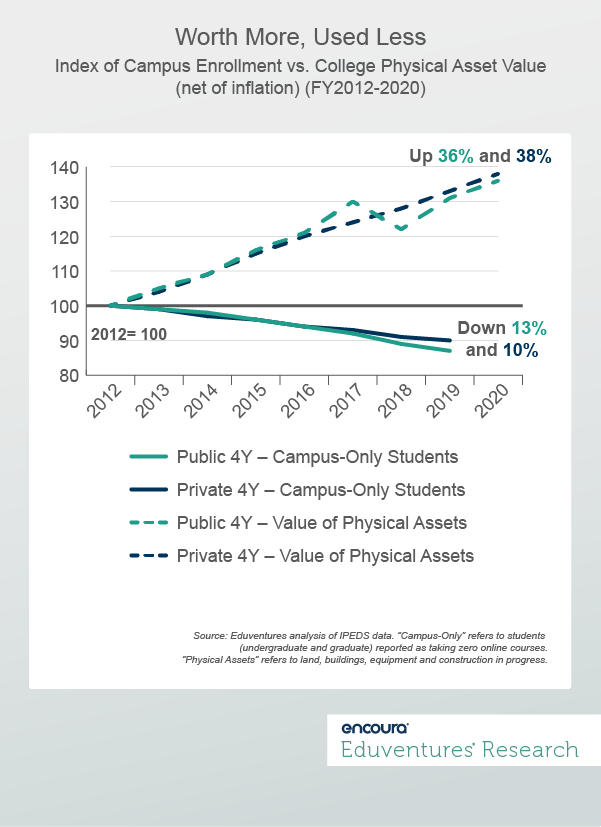

Figure 1 shows a steady fall, pre-COVID, in the number of “campus-only” students in American higher education (four-year schools). The irony is that physical college assets are worth more than ever in dollar terms yet more students never set foot there.

Of course, the picture varies by institution type. For example, highly selective private R1s posted a modest increase in campus-only students over the period, while less selective private M1s and public R3s witnessed an almost 20% decline.

It goes without saying that post-2019, the pandemic shunted huge numbers of students into remote learning. While temporary, the experience only increased exposure to campus alternatives. Inflation will push more students online.

Assets also vary by school, but the total is eye-popping: in FY20, four-year institutional physical assets were valued at just over one trillion dollars. With prices climbing higher still during the pandemic, college campuses may be worth as much as $1.2 trillion today.

Should institutions sell off under-used buildings and invest in the latest edtech? Is a new asset-lite higher education business model on the horizon?

“There is no need to come to campus”

Schools face an immediate dilemma and a longer-term one. Short-term, staring down inflation, enrollment worries, and online drift, institutions are caught between rising costs and not wanting to raise tuition for fear of dampening student interest. Seeking bids for some peripheral assets in a hot property market makes sense, as do other cost-saving measures such as program rationalization and shared back-office services.

The bigger question is the long-term relationship between assets and students.

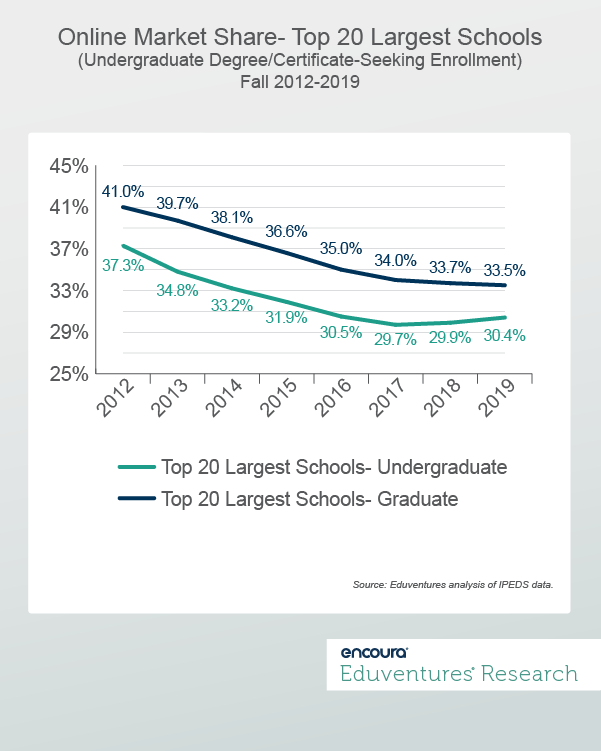

Presidents should think twice about going too far down the online path. Figure 2 traces the share of undergraduate and graduate fully online enrollment held by the 20 largest institutions pre-pandemic.

The online Top 20 ratio fell steadily for much of the decade, from a high of 41% for the Top 20 graduate schools and 37% for undergraduate, to a low of 33.5% and 29.7%, respectively, fragmenting the online market across ever-more institutions. But in 2018, the graduate trend began to flatten and actually reverse among undergraduates.

This points to the formidable scale, resources, and sophistication of the biggest online schools, led by the likes of Western Governors University and Southern New Hampshire University. These institutions are working to turn size to operational and experiential advantage: offering students the most programs, the best services, and superior technology, super-charged by massive marketing spend.

The online Top 20 is exceptionally high when you consider that the same ratio for all graduate students is 16% and just 8% for undergraduates. If the lines in Figure 2 indeed go into reverse, this is bad news for the vast majority of institutions that will struggle in this winner-takes-all scenario. Yet numerous schools are aping the online giants: offering more online programs and reassuring students that they need never come to campus.

But this is a strategic mistake.

“I want to come to campus”

The physical assets of Western Governors University, the nation’s largest wholly online school, and one of the most affordable, were worth $21 million in FY20. That is a mere $111 per student, compared to the private four-year average of $49,000 per student.

How should presidents assess such divergence?

The lesson is that it is very much possible to run an asset-lite university, offer high quality programming, and attract lots of students. But also that the fully online experience necessitates experiential trade-offs. The opportunity is the massive amount of under-occupied middle ground between $111 and $49,000 in physical assets per student that few schools are exploring: figuring out where campus or other in-person experience is essential, where online is superior or will do, and how to optimize cost as well as value.

This decade will see how big online higher education can become and how physical campuses, from community colleges to research universities, counter and adapt.

Schools are beginning to get creative. For example, Brown University’s BE Brown initiative seeks to enroll more students, boost productivity, and enhance experiential learning. More undergraduates will spend a semester or more away from Providence engaged in internships and other experiences, connected by online learning. This will free up space for additional students on campus, allowing the university to raise class sizes.

The campus is an asset and a constraint. Brown’s vision is to use online to transcend campus limitations while also widening access to campus fundamentals.

Bottom Line

As the pandemic ebbs, presidents are unsure whether to hail “back to campus,” even if cost prohibitive and waning in popularity, or pivot to more flexible scenarios. The answer to both is “yes.”

The dollar value of campus assets represents only a modest multiple of revenue. For example, across private four-year schools, physical assets were worth $440 billion in FY20, but in the same year those institutions brought in $237 billion in revenue (comfortably more than expenses at $222 billion). Revenue passes asset value in under two years. True value is the revenue assets generate for institutions when put to good use.

Elite schools like Brown have resources and applicant pools most schools can only dream of. But all the more reason why regular institutions, more vulnerable to market shifts, need to get serious about student experience reinvention that captures the best of campus and online. The good news is that for years, the Eduventures prospective student surveys—traditional, adult and graduate prospects—have shown more interest in forms of hybrid than available in the market.

Eduventures has helped a growing number of clients think through hybrid strategies. Have an idea? Please get in touch.

Never Miss Your Wake-Up Call

Learn more about our team of expert research analysts here.

Eduventures Chief Research Officer at Encoura

Contact

This recruitment cycle challenged the creativity of enrollment teams as they were forced to recreate the entire enrollment experience online. The challenge for this spring will be getting proximate to admitted students by replicating new-found practices to increase yield through the summer’s extended enrollment cycle.

By participating in the Eduventures Admitted Student Research, your office will gain actionable insights on:

- Nationwide benchmarks for yield outcomes

- Changes in the decision-making behaviors of incoming freshmen that impact recruiting

- Gaps between how your institution was perceived and your actual institution identity

- Regional and national competitive shifts in the wake of the post-COVID-19 environment

- Competitiveness of your updated financial aid model