A once-in-a-century event like the COVID-19 pandemic is a reminder of the foolishness of making predictions. But COVID has also shaken everything up, giving prognosticators like me even more variables to work with for my Higher Education Predictions for 2022.

My three 2022 predictions speak to some potentially disruptive variables facing higher education in our COVID-normal landscape:

- The Inflation Monster & College Reform: dormant for decades, inflation is heating up in today’s fragile enrollment environment, but will convince some bold colleges to embark on invaluable reforms.

- “Gainful” Returns—But Will Not Succeed: gainful employment, the most controversial plank of Obama-era higher ed regulation later gutted by litigation and Betsy DeVos, is on the agenda for 2022 negotiated rulemaking. To the relief of many colleges, I predict “Gainful” will sputter again.

- State OPMs—Other States to Follow North Carolina’s Lead: other states will imitate North Carolina’s “Project Kitty Hawk” state-OPM move as a high-stakes but compelling way to ride the online learning wave AND reassert the role of the state.

Prediction 1: The Inflation Monster & College Reform

Inflation hit 6.9% in 2021, the highest rate in 40 years. Just as schools are tempering prices to convince skittish students to enroll, pandemic-ravaged supply chains, enormous fiscal stimulus, and labor shortages are pushing college inputs up sharply.

What does this mean for colleges and universities in 2022? The implications are serious, and the impact is already visible: 2021-22 saw the first across-the-board (i.e., public and private, two-year and four-year) average constant dollar list tuition decline since 1980-81—a drop of about 2% regardless of sector. Schools raised prices, but inflation gulped the gains.

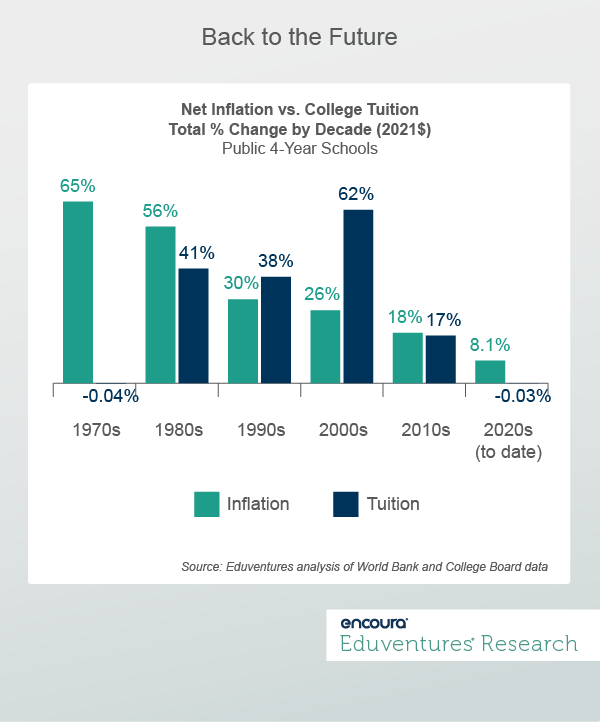

Higher education has been here before. Figure 1 contrasts inflation and college tuition by decade. The chart concerns public four-year schools, but similar trends sustained at private four-year and public two-year institutions.

In the 1970s, inflation rocketed up 65%, but college tuition at public four-year institutions was lower in 1979 than in 1970, measured in constant dollars. Yes, you read that right: colleges faced input prices 65% higher than 10 years before. They jacked up tuition, but the inflation monster swallowed all price gains.

Imagine raising tuition by 65% and getting zero extra dollars for investment! No doubt extra financial aid for cash-strapped families undermined headline tuition even further. Inflation does not play.

Enrollment tanked in the back half of the 70s, coming in lower in 1979 than 1975. This period coincided with a boom in 18-year-olds, but enrollment went south, nonetheless. Blame the ravages of an unstable economy and consumer doubts about return-on-investment for (at the time) sky-high tuition.

From the late 80s through the 1990s and 2000s, as inflation eased, colleges made up for lost ground, posting tuition hikes way above cost-of-living increases. Then the narrative changed: colleges were accused of turning every Pell or federal loan increase into an “excuse” to raise prices. Schools priced rather than reformed their way out of the inflation monster’s jaws.

Things will be different this time, in my opinion.

By the second half of the 2010s, even record low unemployment could not rouse the inflation monster. But colleges did not crank up tuition and in fact began to moderate increases, navigating a combination of demographic challenges, rising wages for people without a degree, and accumulated anxiety about the college price-value equation after seemingly endless above-inflation tuition rises.

What now? With inflation spiking, many colleges now face the devilish combo of falling enrollment and eroding buying power, risking a vicious circle.

Even if today’s inflation spike proves short-lived, I predict that these rare circumstances will convince some colleges—those outside of the elite—to rationalize in ways no amount of media tutting and regulatory stipulation will be able to manage.

No demographic wave is coming to the rescue this time, and it is far-fetched to believe that, once the inflation monster is tamed, colleges can resume above-inflation tuition increases indefinitely.

Enrollment troubles will be more manageable for the schools that sunset less-strategic, low enrollment programs, invest in market-friendly degrees and degree alternatives, and make greater effort to leverage the cost efficiencies of the massive edtech investment prompted by the pandemic.

In 2022, expect to see more colleges touting mission-aligned programming, back-office automation, consortium productivity, and hybrid learning models that keep costs down. See Prediction #3 for a bold example from North Carolina.

Prediction 2: “Gainful” Returns, But Will Not Succeed

Program-by-program checks on which colleges offer value-for-money? For some, this might sound like a regulatory or parental dream come true; for others it smacks of government overreach and portends a bureaucratic nightmare.

Back in 2011, in the wake of the Great Recession, when for-profit higher education was at its peak, this program-level value idea—termed “Gainful Employment” regulation—was fashioned by the Obama Administration to counter the sector’s excesses. To remain eligible for Title IV funds, all for-profit schools would have to show, program by program, evidence that graduates earned a living wage and could repay student debt.

In short, “Gainful Employment” regulation, over the following decade, was modified, delayed, watered down, and finally terminated under Trump.

But the idea never went away. Many Democrats continue to want to corral wayward for-profits, and some Republicans see fault in “Gainful” for applying to only for-profit schools. Lawsuits brought by the American Federation of Teachers and others to compel the Department to reinstate “Gainful” are ongoing.

A re-run is about to begin: “Gainful Employment” is named as one of various topics for the next round of negotiated rulemaking under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Education to begin in early 2022.

“Negotiated rulemaking” refers to the process by which the Department seeks input on current or proposed regulation, convening a panel of negotiators who represent institutions and other constituents. Rulemaking interprets existing legislation so does not require action by Congress.

Right now, details are scarce. It is not clear whether the Department wishes to focus on for-profits only, expand “Gainful” to nonprofits, or re-think program criteria.

My prediction is that negotiators will consider the merits of “Gainful” for all but be unable to reach consensus. The Department, then free to implement its preferred approach, will craft a fiendishly complicated “Gainful Employment 2.0” but this will succumb to relentless lobbying by nonprofit and for-profit school associations alike. As the mid-terms shift the balance of power, son-of-Gainful will, like its parent, prove too threatening and complicated for its own good.

Officials and lawmakers will come to see today’s market forces, not least the inflation monster of Prediction #1, as sufficiently fierce to keep schools laser-focused on value-for-money.

Prediction 3: State OPMs - Other States to Follow North Carolina’s Lead

Caught between the entrepreneurship of individual institutions and the commercial practicality of Online Program Management companies (OPMs), states have long looked like online higher education’s spare wheel. When technology says geography is irrelevant, state higher education systems can seem like an anachronism.

In the early days of online, states took the initiative, crafting collectives to make the most of limited system resources. The for-profits were coming, and states saw sense in collaborating rather than leaving each school to fend for itself. But ambitions faltered as state consortia struggled to overcome higher education’s decentralizing tendencies and many were left administering clunky systemwide online program portals and running cheery webinars.

The online action was elsewhere.

Fast forward to 2021, and many states fret about how many residents enroll at aggressive out-of-state schools and how much money “their” schools are handing over to OPMs because they do not have what it takes to succeed online.

Enter “Project Kitty Hawk” (PKH), University of North Carolina’s $97 million state OPM-to-be. PKH will, backers envision, do everything an OPM does but at lower cost and with the state's needs front-and-center. In my view, PKH is the most ambitious state online higher education initiative in a long time, reviving the notion that system cooperation is smarter than leaving online to individual institutions.

There is nothing special about North Carolina. For its size, it is average when it comes to volume of online students and programs. But that is what makes PKH special. The initiative is a nod to an underappreciated truth in the evolving online higher education market: most schools will falter in an online future where geography does not matter. If scale and reach win, if biggest is best, if student-institution co-location is not pedagogically important, then funding a state OPM makes no sense.

But if the big flaw in the winner-takes-all version of online is precisely lack of attention to enduring local needs, then a state OPM may prove the right balance between local and global. Insofar as localities differ in terms of industries, learners benefit from in-person and hands-on experiences as well as online convenience, and intimacy sometimes trumps scale, a state OPM could help public higher education systems thrive.

I predict that at least two other states will announce moves similar to Project Kitty Hawk in 2022.

I am the first to acknowledge that the road ahead is difficult for PKH: leaders must avoid the temptation to imitate the online giants, stressing convenience above all. They must convince skeptical University of North Carolina (UNC) institutions, accustomed to fending for themselves online, that working with the new OPM will do anything other than slow them down. Getting 16 UNC campuses to agree on a common online strategy and division of labor cannot be imposed from the center.

But I do see Project Kitty Hawk as a clarion call for public higher education systems in an online world, and a welcome rejection of one-size-fits-all solutions.

Thanks for reading. As always, at the end of next year, I will look back at my three predictions and assess what really happened.

Never Miss Your Wake-Up Call

Learn more about our team of expert research analysts here.

Eduventures Chief Research Officer at Encoura

Contact

Wednesday January 26, 2022 at 2PM ET/1PM CT

As we kick off a new semester, it's a great time to remember one of your most important stakeholders: alumni. What new strategies do you have for this upcoming semester to engage with your alumni in a refreshing and personal way that reminds them of their pride for your institution?

In this webinar, VP of Encoura Digital Solutions Reva Levin and Director Lyndenise Berdecía will share why an omnichannel approach is the most effective way to connect with alumni and drive genuine giving. They’ll also describe how and when to implement this approach in order to help any institution have a more successful giving season.

The Program Strength Assessment (PSA) is a data-driven way for higher education leaders to objectively evaluate their programs against internal and external benchmarks. By leveraging the unparalleled data sets and deep expertise of Eduventures, we’re able to objectively identify where your program strengths intersect with traditional, adult, and graduate students’ values so you can create a productive and distinctive program portfolio.