Remember the days when $25 million was considered a really big gift? The kind that could help anchor ambitious comprehensive campaigns? The kind that was celebrated with extensive press coverage, ribbon-cutting ceremonies, even parties? At some point not so long ago, this benchmark inched up to $50 million, then to $100 million…

Now, reporters tell me they don’t even consider writing about a gift unless it amounts to hundreds of millions of dollars. Why should they? This year alone, we’ve seen a $400 million gift to Harvard, a $300 million gift to Yale, and a $150 million gift to Princeton. This follows a year of gifts in the several hundred-thousand dollar range to Johns Hopkins and Harvard, among others. Notably, these are some of the most elite schools in the country.

While reporters may only be focused on multi-hundred million dollar gifts, most schools still have to focus on attracting gifts in the $5 million to $25 million range in order to meet their goals. Even at this level, it’s becoming increasingly challenging to compete in today’s climate. Earlier this year, Moody’s released a report that shined a light on the widening gap in wealth among institutions of higher education. The more wealth that schools with large endowments—Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and their peers—accumulate, the higher the returns they are able to get.

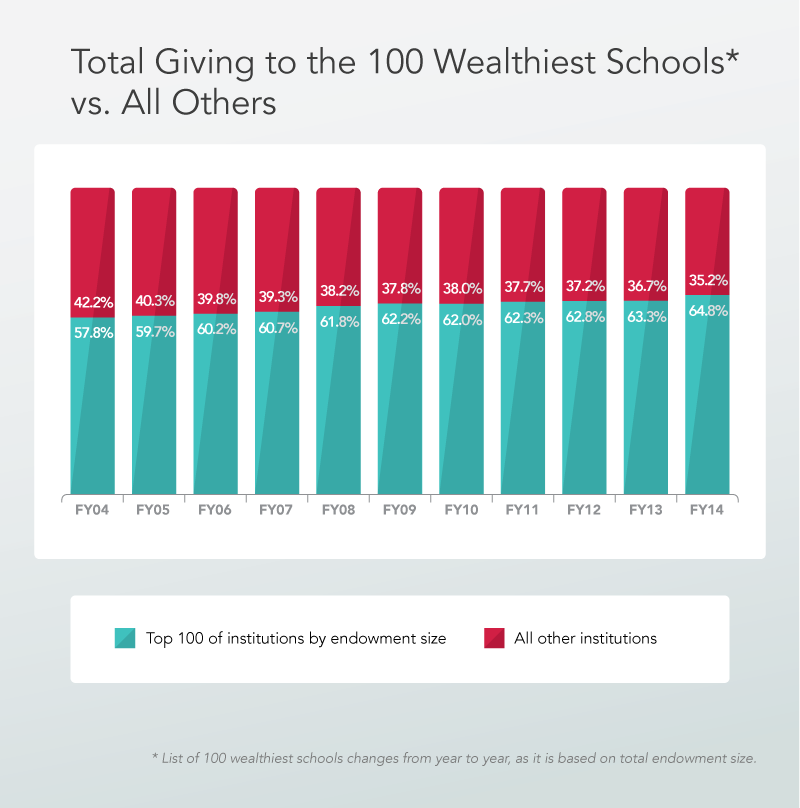

These schools also receive a larger share of fundraising revenue. Crunching a few numbers reveals that when it comes to philanthropic support, the wealth gap has been growing for the past decade:

Today, 65% of total fundraising dollars goes to the 100 wealthiest schools in the country. This figure has risen seven percentage points over the past decade. Given the widening wealth gap in the general population, it’s not a great leap in logic to assume that this trend will also likely continue for higher education philanthropy.

What if your institution is not among the 100 wealthiest schools?

Chances are, it’s not. What likelihood do you have of capturing a piece of this pie? Regardless of where your school falls, there is a lesson to be learned from another philanthropic event from 2015, one that doesn’t quite fit the mold.

In June, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) reached a goal of $500 million in total philanthropic and government support. Reaching this milestone allowed OHSU to secure an unprecedented challenge pledge of $500 million that Phil Knight, co-founder of Nike, and his wife, Penelope, made in 2013. The gift is the largest on record for an institution of higher education and will be used to support research on the early detection of cancer.

Other than its sheer size, what makes this gift stand out? Unlike many schools receiving gifts of this size, OHSU is notably not among the 100 wealthiest schools in the country. Knight is also not an alumnus of OHSU. In fact, he’s an alumnus of its neighbor to the south (University of Oregon), to which he has also given generously.

Why did Knight choose to make such a big gift to a school he did not attend? According to Eduventures Alumni Giving data, if Knight had been motivated by the same factors that motivate OHSU alumni, then he was likely very sold on its mission. Maybe he wanted to see his name more deeply associated with a cause that has touched his life. Maybe he wanted to support an organization in the community in which he lives rather than one many miles away.

Whether or not your institution is wealthy and whether a mega gift for you is $1 million, $100 million, or somewhere in between, every school can benefit from taking steps to put big gifts of any size within reach. The lesson here is threefold:

- First, focusing on alumni prospects is a sound strategy for schools that graduate some of the wealthiest alumni in the country, but it’s just not enough for most programs. In many ways, a new era of fundraising calls for higher education advancement to think more like non-profit organizations. This includes proactively identifying prospects outside of your alumni base and developing the right infrastructure, such as engagement opportunities and tailored prospect strategies. In other words, homecoming weekend may not resonate. The gap between alumni and non-alumni giving has narrowed in recent years; in 2014, 40% of all million-dollar gifts came from non-alumni, compared to 35% in 2006. Phil Knight made the gift of a lifetime to a school that was located in his own community but that he did not attend. Someone like him could be in your backyard too. In fact, more than 60% of million-dollar gifts come from donors who live in the same region as the institution.

- Second, only big ideas attract big gifts. It’s simply no longer enough to focus on initiatives that serve to strengthen our institutions. We must focus on how our initiatives improve the world beyond our halls. The big ideas guiding fundable mega-gift opportunities can’t only be big by our standards, they must actually be big. Make sure the vision for your big idea is crystal clear. In this case, Knight’s big gift to OHSU had the potential to be life changing for people the world over, which inspired mega gifts from other philanthropists, significantly magnifying its impact. When the value proposition of a big idea is evident, big gifts are within reach.

- Third, when it comes to coming up with “big ideas,” donors are a critical part of the process. Eduventures data indicates that the largest single source for originating “big ideas” is not the university president, development office, or deans. The single largest source of big, fundable ideas is the donors themselves. You can bet that Knight had something to do with the “challenge” aspect of his gift. While OHSU may have asked for an audacious amount, reporting about this gift indicates that he was the architect of the conditional challenge portion of this gift, ultimately doubling the potential impact his gift could have had on its own.