“Just one more question.” At the end of an Eduventures advising session with a university client, the vice president of enrollment said something intriguing. “The presidents’ cabinets have long been familiar with data showing falling high school graduates in our state [in New England]. The downturn helped explain the decline in our freshman class in recent years.”

So far, so familiar.

“Well, some people on campus took a fresh look at the data and think that high school graduate numbers have actually been stable. Is the downturn just a ”

A challenge to conventional wisdom is something any analyst relishes, so we were quickly on the case. What did we find?

In 2016, the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) published the latest edition of its Knocking on the College Door series, a state-by-state analysis of recent trends in high school graduate numbers, plus 15-year forecasts. The current edition said that all of New England states, and many others, were in the early stages of a prolonged fall in high school graduate numbers driven by a drop in birth rates—a decline that would continue into the 2020s and beyond.

Knocking on the College Door is a great resource, permitting straightforward comparison between states and over time. Not surprisingly, numerous colleges and universities have factored these forecasts into their strategic plans, just as WICHE intended.

But this becomes a problem if the received wisdom turns out to be wrong. In this case, the evidence was hidden in plain sight. Anyone can go to their state’s education department website, look up the high school graduation stats and compare them to WICHE’s figures.

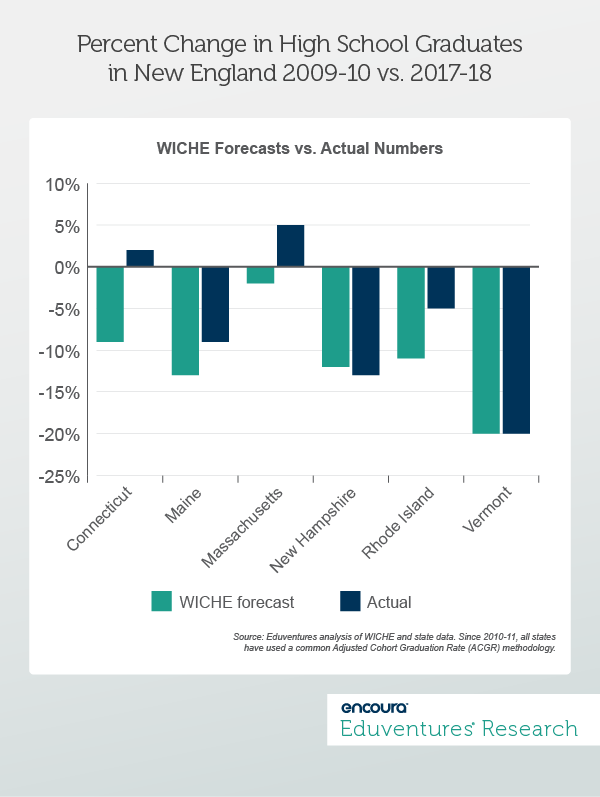

We did just that, for all six New England states (Figure 1).

Based on WICHE’s predictions, high school graduates—public and private—in New England were set to fall 7% between 2010 and 2018. In reality, the total fell by only 1%.

In two states, New Hampshire and Vermont, WICHE was on target; but in the other four, high school graduate numbers defied expectations. Declines were less severe in Maine and Rhode Island, and Connecticut and Massachusetts posted net gains.

How do we explain the gap between WICHE’s projections and reality?

More research is needed, but net migration appears not to be a big factor. According to U.S. Census data, the two states that had more high school graduates in 2018 than 2010, Connecticut and Massachusetts, tended to lose more residents than they gained over this period. Maine and Vermont gained residents, but mostly retirees, meaning little impact on high school enrollment.

Volatility in private high school enrollment, less closely tracked than the public variety, threw off some WICHE forecasts, as the organization acknowledges.

A key explanation for the differences between WICHE’s numbers and what actually happened is an improvement in the graduation rate itself. The public high school graduation cohort dropped 2.5% in Massachusetts over the period, but the graduation rate jumped 7%, producing a bigger number of high school graduates. Something similar happened in Connecticut: the public cohort slumped by 5% but the graduation rate climbed by 8%. More modest graduation rate gains in Maine and Rhode Island help account for smaller losses than forecast by WICHE.

Of course, a higher graduation rate does not necessarily mean every graduate wants or is able to go to college, or is college-ready.

What happened to first-time college enrollment in New England during these years? The institution that inspired this Wake-Up Call has seen falling undergraduate enrollment. Yet the number of high school graduates in the institution’s state grew modestly.

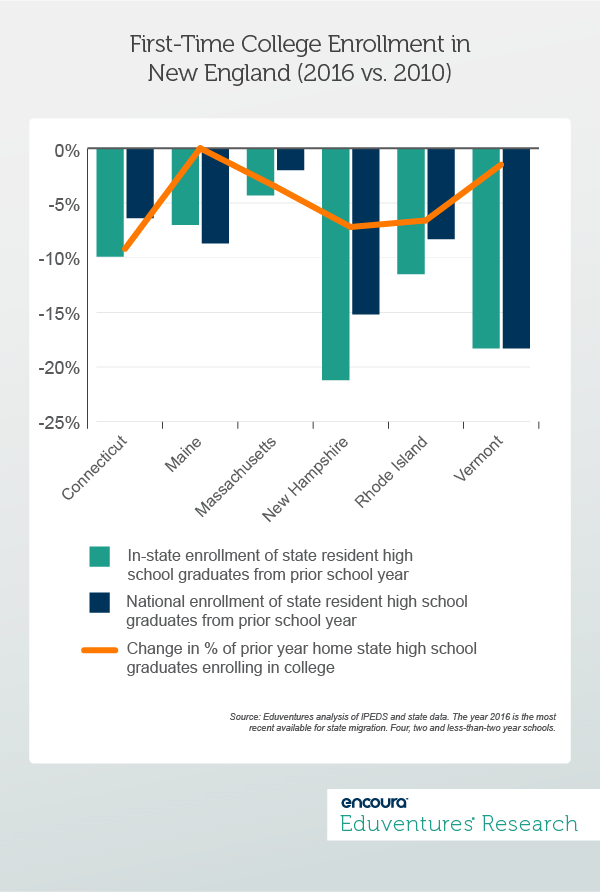

Figure 2 considers college-going trends among New England’s high school graduates.

In Figure 2, the green bar is the growth in state residents who graduated from high school in the prior school year and then enrolled in a college or university in the same state. For example, in Connecticut this total fell 9.9% between 2010 and 2016. But the blue bar—showing higher education enrollment in any state by local recent high school graduates—fell only 6.4%.

This pattern—where enrollment of recent high school graduates in in-state institutions dropped more markedly than their enrollment in colleges nationally—is visible in five of the six New England states. This means that out-of-state schools have been competing away New England high school graduates at a time when this population has been at best stable and at worst in sharp decline.

Only Maine schools managed to out-perform, consistent with the state’s Educational Opportunity Tax Credit, a state effort to help students pay off debt. Originally, only Mainers who enrolled at a Maine institution were eligible, but the scheme is now available to anyone with student debt who relocates.

The orange line indicates the change in the proportion of recent high school graduates in each state who enrolled in college, in any state, the year after graduation. That percentage—again except for Maine, which was flat—fell between 2010 and 2016. Fewer high school graduates opted to enroll in college right away. This may reflect a stronger economy but may also belie flattering gains in high school graduation rates. A growing number of graduates may not feel ready for college, or see a way to manage tuition, or may have other education or career pathways in mind. This may be consistent with shifting high school demographics in favor of less “traditional” students.

Not shown is a third variable: concentration of enrollment. In Connecticut and Massachusetts, the leading public universities, University of Connecticut and University of Massachusetts, Amherst—grew first-time enrollment of state residents by 16% and 5% respectively, even while overall enrollment of state residents by local schools in each state slumped. But in the four smaller New England states, the flagships struggled like everyone else. In these states, the combination of big drops in high school graduate numbers and more limited institutional variety makes it more challenging to buck the trend.

The Bottom Line

Our client was right to question conventional wisdom: in Connecticut and Massachusetts at least, high school graduate numbers have in fact grown over the past decade or so, contrary to WICHE’s forecasts. Improved graduation rates are a key factor. In these states, college and university leaders cannot simply blame fewer high school graduates for their enrollment woes.

Eduventures analysis shows that the decline in first-time enrollment suffered by our client school and many others in the region—despite high school graduate numbers holding up—can be attributed to at least three things:

- Increased out-of-state competition

- A drop in the college-going rate across the region

- Leading universities taking market share

In summary, stable-to-down high school graduate numbers have been made worse by fewer college-going students, the charms of out-of-state schools, and flagship opportunism.

WICHE’s Knocking at the College Door is an invaluable resource, and an exercise this ambitious cannot expect to get everything right. Indeed, we invite a critique of our own analysis. Many of WICHE’s forecasts will prove accurate, but every school should check their state’s high school graduate numbers to make sure. (As we have noted in previous Wake-Up Calls, longer-term demographics do not look good for higher education, not least in New England. Stretching high school graduation rates can only hold the tide for so long).

We discussed our findings with WICHE. To their credit, WICHE welcomes analysis of their forecasts, and offered some useful comments on this post.

To conclude, tracking high school graduates is important. A more fundamental question is: why is the college-going rate going down?

Wednesday November 20, 2019 at 2PM ET/1PM CT

We often overlook library management systems in discussions of higher education technology. Unfortunately, doing this allows us to miss valuable lessons that library technology leaders have addressed. Unlike the world of enterprise IT (student information systems, etc.), library management leaders have developed exciting ways to handle decentralized technology ecosystems and manage integration between solutions. In this webinar, we will compare and contrast the prevalent implementations of enterprise IT and library management solutions.

Thank you for subscribing!

Thank you for subscribing!