The daily drumbeat of cyber crime appears to have no boundaries. Recent testimony to the Senate Finance Committee revealed that hackers compromised up to 100,000 FAFSA (Free Application for Federal Student Aid) applicants, leading to the suspension of the online tool last month. A February 2017 attack on more than 60 universities by a Russian hacker known as Rasputin came on the heels of assaults on a wide range of institutions from the United States Postal Regulatory Commission to the Rhode Island Department of Education.

Of course, these examples don’t even include the events of the 2016 political season.

As terms such as “password hashing” and the “fuzzy hack” enter our lexicon, both established institutions and non-traditional training providers are rapidly attempting to respond to one of the greatest employment and skills gap of recent memory. Currently, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports that 209,000 cybersecurity jobs remained unfilled; recent forecasts suggest there could be 1.5 million cybersecurity vacancies worldwide by 2019.

Additionally, a recent analysis of job posting frequencies by Economic Modeling Specialists International (EMSI) revealed an 18% increase in cybersecurity analyst jobs since 2011 , distributed among more than 31,000 companies in the U.S. alone. From 2016 to 2017, there were more than 32,000 unique U.S. job postings added each month.

While some observers hail cybersecurity as the next great enrollment gold rush, there is less clarity about the contours of this discipline and how schools and other providers can effectively respond to this demand. Beyond simply recognizing the growing demand for cybersecurity professionals, it’s critical to note that there’s a broad spectrum of roles, skills, and technical requirements within the umbrella of “cybersecurity.”

The field, and its growing employment demand, is best understood as a range of discreet yet interconnected functions, including risk assessment, data monitoring, system scanning, and responding to actual attacks. These skills tap into many academic disciplines, such as business strategy, engineering, and criminology, requiring a blend of both technical expertise and industry-specific domain knowledge. Recent studies estimate that more than 80% of cybersecurity job openings require at least three years of experience plus a bachelor’s degree, and more than a third of these openings will require an industry-validated certification.

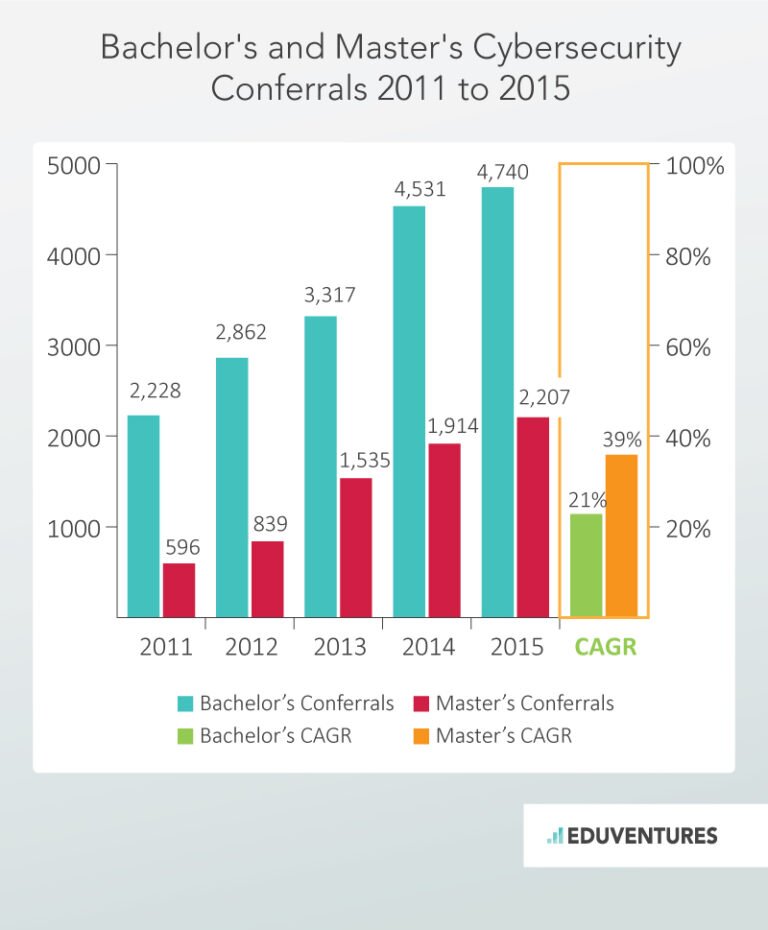

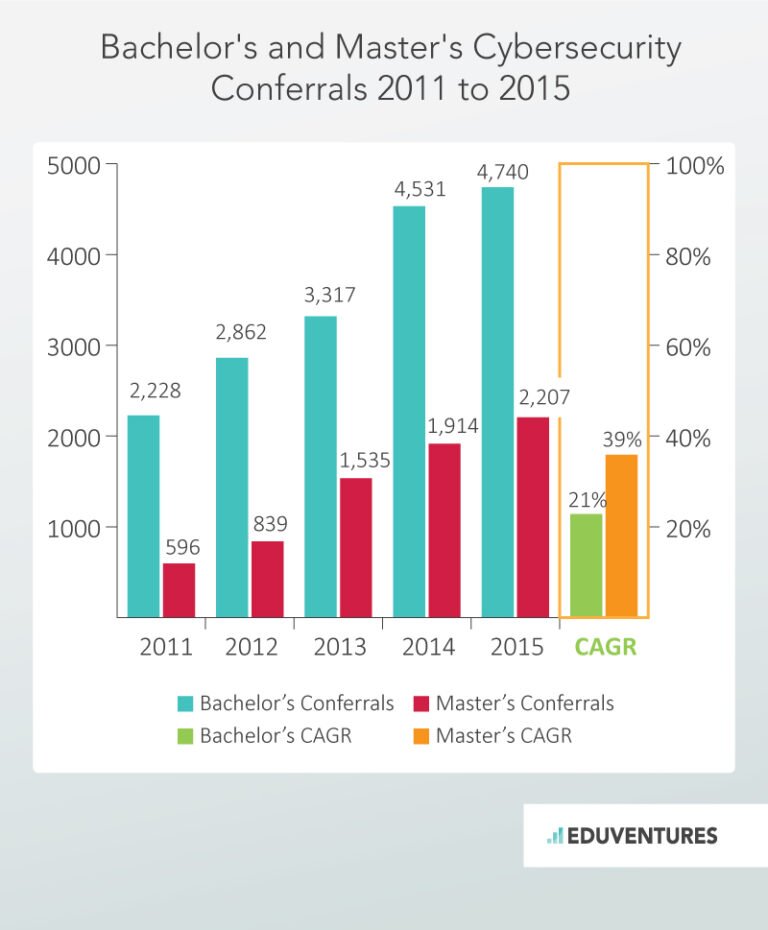

These requirements suggest that the widest part of the cybersecurity enrollment funnel will be mid-career adult learners seeking to sharpen their employment opportunities. Eduventures’ own analysis indicates that, between 2011 and 2015, graduate conferrals have grown by 39% while undergraduate conferrals have grown 21%.

Although there are more cybersecurity bachelor’s degrees granted each year, the average number of conferrals per provider trends higher at the graduate level. Fewer graduate providers granting more degrees suggest slightly less competition for schools entering this market for the first time.

The uptick in cybersecurity job demand is not only about volume, but also about diversification. As cybercrime spreads, organizations of all sizes and types have to rethink their infrastructure and personnel needs. Both the complexities of the cybersecurity field and recent enrollment dynamics pose a number of considerations for schools either expanding existing cybersecurity programs or seeking to enter the field for the first time:

Although there are more cybersecurity bachelor’s degrees granted each year, the average number of conferrals per provider trends higher at the graduate level. Fewer graduate providers granting more degrees suggest slightly less competition for schools entering this market for the first time.

The uptick in cybersecurity job demand is not only about volume, but also about diversification. As cybercrime spreads, organizations of all sizes and types have to rethink their infrastructure and personnel needs. Both the complexities of the cybersecurity field and recent enrollment dynamics pose a number of considerations for schools either expanding existing cybersecurity programs or seeking to enter the field for the first time:

Although there are more cybersecurity bachelor’s degrees granted each year, the average number of conferrals per provider trends higher at the graduate level. Fewer graduate providers granting more degrees suggest slightly less competition for schools entering this market for the first time.

The uptick in cybersecurity job demand is not only about volume, but also about diversification. As cybercrime spreads, organizations of all sizes and types have to rethink their infrastructure and personnel needs. Both the complexities of the cybersecurity field and recent enrollment dynamics pose a number of considerations for schools either expanding existing cybersecurity programs or seeking to enter the field for the first time:

Although there are more cybersecurity bachelor’s degrees granted each year, the average number of conferrals per provider trends higher at the graduate level. Fewer graduate providers granting more degrees suggest slightly less competition for schools entering this market for the first time.

The uptick in cybersecurity job demand is not only about volume, but also about diversification. As cybercrime spreads, organizations of all sizes and types have to rethink their infrastructure and personnel needs. Both the complexities of the cybersecurity field and recent enrollment dynamics pose a number of considerations for schools either expanding existing cybersecurity programs or seeking to enter the field for the first time: