In an environment where college tuition continues to march ahead of inflation and the student debt balloon grows bigger every year, Our 2019 Online Higher Education Market Update report analyzes published tuition by intensity of online enrollment. On average, fully online schools charge the least at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. Controlling for inflation, undergraduate list price at fully online schools has actually declined in recent years, compared to steady increases elsewhere.

Problem solved? Not so fast. To understand the online learning economy, we also need to consider school spending and indicators of quality.

Let’s start with spend. The common assumption is that the underlying costs of online learning are much lower than those of a physical campus and there is greater scope for economies of scale – hence that low tuition. A 2017 WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies (WCET) survey of online leaders pushed back against such notions, painting a picture of online learning—done well—as often more time-consuming and expensive than the in-person norm.

Cynics might argue that fully online schools are cheap because they are low quality. So who’s right?

Love the Savings

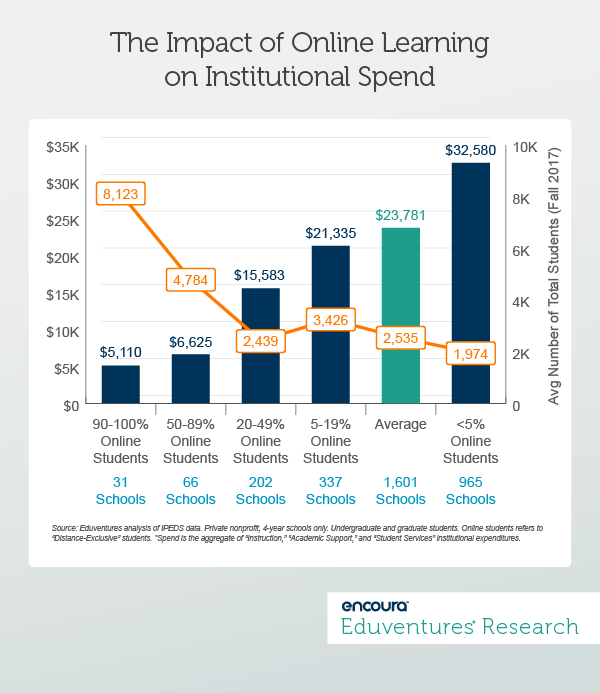

Figure 1 breaks out, by intensity of online enrollment, average institutional spend per student on instruction, academic support, and student services. These are the three spend categories the U.S. Department of Education uses to collect data on institutional expenditures related to academics and extracurricular activities.

To limit the number of variables in play, the data in Figure 1 is confined to private, nonprofit four-year schools. This large and diverse group of institutions exhibits a wide array of online learning activity—from online giants such as Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU) and Western Governors University, to institutions with no online students at all.

On average, fully online schools spend a lot less, about $5,000 per student, compared to an average of almost $24,000 for all other schools—nearly five times as much. Private nonprofit schools with 5% or fewer fully online students spend an average of $32,580 per student—over six times the average fully online schools spend.

Economies of scale are apparent. The fully online schools reported an average of over 8,000 students in fall 2017, compared to under 2,000 for schools where fewer than 5% of students were fully online.

Fully online colleges also tend to employ few (expensive) full-time faculty, a cost reduction measure unrelated to delivery mode. At some online schools, many students are part-time. Using full-time equivalent students might close the gap in Figure 1 somewhat.

There are also notable differences by type of spend. Schools with lower online student intensity tend to spend relatively more on instruction, while fully online schools devote proportionally more resources to academic support and student services. These spending differences may reflect the more self-paced character of most online programs: bigger spend on course development up front and less on live instruction.

To summarize, much lower average fully online school spend per student may be explained in terms of institutional ability to scale, and a distinct instructional model not dependent on expensive physical facilities. While online learning comes in many varieties, including labor-intensive forms of synchronous delivery, the norm is asynchronous.

What About Quality?

Quality is much harder to define and quantify. Fully online and traditional schools confer degrees with the same titles and enjoy the same accreditation. As discussed in our recent Online Higher Education Market Update, undergraduate completion rates for fully online schools tend to be lower than those at more traditional schools—by about a third to half. Skeptics say this shows online learning is lower quality, while advocates retort that a less traditional student body is the culprit.

But even if the online completion rate is half the campus benchmark, does the 80% cost reduction more than make up for it? Put another way, more systematic investment in online learning, across a wider swath of U.S. higher education, might permit a happy medium: greater economies of scale for most schools pushing spend per student down, but still resulting in higher spend per student (than the fully online average) to close the online completion gap.

There is some evidence that this is happening. Increased investment in online learning by numerous schools over the past five years, shown in the steady growth in online student numbers in an otherwise flat enrollment environment, suggests that the sector as a whole may be reaping the cost benefit. This may be holding down overall costs and reining in tuition.

Indeed, controlling for inflation, average institutional spend per student on instruction, academic support, and student services was flat between 2012 and 2017. By contrast, spend at the schools with the least online students, including many with none, grew 6%.

A striking trend is that while average spend per student was flat over the past five years, average expenditures jumped 52% at fully online schools! Circumstances vary by institution, but this leap may signal major efforts to close the completion gap and improve the online student experience overall. Fully online schools are seeking that happy medium.

In the final analysis, attempting to “prove” that online and campus-based learning are the “same” quality is impossible. Too many variables are in play—types of students, fields of study, and selectivity—and comparing grades or graduation rates reveals little about learning quality or student capability on either side. Similarly, going head-to-head on alumni wages is a poor proxy for quality or value.

You Can Have it All…

The question is whether the average school (see Figure 1) is pursuing online learning with both quality and cost efficiency in mind. WCET’s survey implies this is often not the case; more online often means higher cost.

At most institutions, online emerged organically, with interested faculty doing their own thing. This was essential to get online off the ground. Thirty years on from the genesis of online learning, a more deliberate and centralized approach may be needed to squeeze out more value.

There is no “right” model to suit all students or all institutions. Creative blends of in-person and online learning, leveraging faculty and technology where each is most effective, will produce the best mix of cost reduction and high quality. Eduventures will continue to analyze enrollment, spend and completion data in search of this future formula. This includes scrutiny of the data for public and for-profit schools.

Look for future Wake-Up Calls reviewing institutional “profit” margins by delivery mode, and spend on people versus technology and facilities. Also, look out for part two of Eduventures Online Higher Education Market Update later this year, focused on local online markets.

Knowing what students care about when they are making their final enrollment decisions is vital to creating a relevant yield strategy. As we look around the corner to Fall 2019 admitted freshmen, now is a great time to learn how specific types of admitted students make their decisions. Doing so will allow you to refine and tailor your next recruitment cycle and yield strategy to meet your goals.

This webinar will cover highlights from Eduventures® Survey of Admitted Students™, an annual study that collects data from more than 100,000 admitted students to help colleges and universities design effective yield strategies. Insights from this webinar will help you to:

- Identify key student Decision Segments™

- Understand where non-enrolling students actually did enroll and why

- Better assess and respond to the competitive landscape