In a previous Wake-Up Call, we looked at the association between online learning and per-student spend on instruction and support services.

At a time of sticker shock, eye-watering discount rates, and ballooning student debt, advocates for online learning see technology as the escape route, to sustain or improve quality and lower cost.

Let's dig a bit deeper now, factoring in wages and benefits as a percentage of spend. Does online learning mean more spend on technology and less on people?

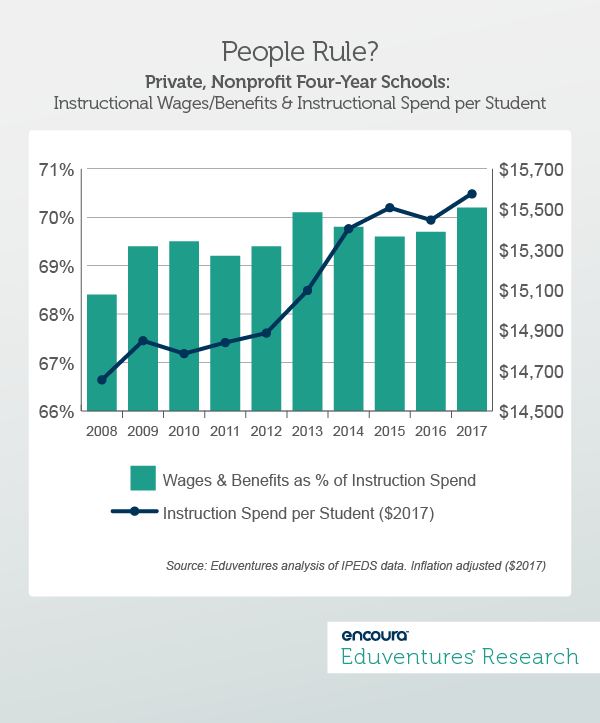

Figure 1 tracks wages and benefits as a proportion of instructional spend at private, nonprofit four-year schools. We have focused on this sector to limit the number of variables at play—similar conclusions might be drawn concerning public four-year schools.

What is striking about Figure 1 is the consistency of wages and benefits as a percentage of total instructional spend. From academic years 2007/08 to 2016/17, the percentage was implacable at about 69%, despite the Great Recession, demographic changes, and hundreds of millions of dollars devoted to educational technology.

Figure 1 suggests that, big picture, educational technology may have enriched the student experience but has not affected the economics of instruction. Faculty and other instructional staff account for an unwavering majority of instructional spend.

The boom in educational technology has also been unable to arrest rising instructional costs. Among private, nonprofit four-year schools, average instructional spend per student—the dark blue line in Figure 1—adjusted for inflation, grew 6% over the period.

Humans are expensive, but this data implies that few private institutions are convinced that technology can reduce cost without reducing quality.

Does intensity of online enrollment make a difference?

We know that online schools spend a lot less per student on instruction than other institutions. But does the prominence of technology at online schools also mean more circumscribed spend on faculty?

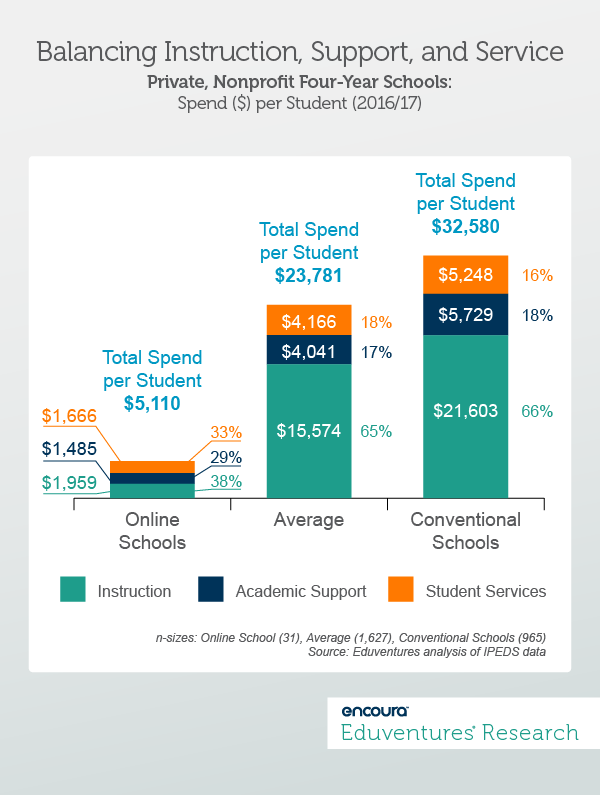

To address this question, it is illuminating to consider spend beyond instruction. Figure 2 compares absolute and relative spend on instruction, academic support, and student services for “online schools” (i.e., schools where 90% or more students are online), “conventional schools” (i.e., schools where fewer than 5% of students are online), and the average for all schools. Again, the focus is private, nonprofit four-year institutions.

There is no question that online schools spend a lot less than average on instruction, academic support, and student services ($5,110 vs. $23,781). But the distribution of the three spend categories is also different. Online schools spend relatively more per student on academic support and student services, and relatively less on instruction.

At conventional schools, instruction accounts for two-thirds of combined spend, but only 38% at online institutions. Academic support and student services each command about 20% each at conventional schools, but about a third of per-student spend at online schools.

Relatively lower spend on instruction and higher spend on academic support and student services may be explained by:

- Greater learner independence and institutional investment in coaches, mentors, and other support staff

- No expenditure on expensive physical classrooms

- Reliance on adjunct faculty

- Support staff paid less than faculty

Online schools spend a lot less per student than average in all three categories, but the contrast for instruction is greatest. Online schools spend only 9% per student of what conventional schools spend on instruction. Counter-intuitively, the bulk of this is devoted to faculty wages and benefits. In fact, online schools spend a relatively higher proportion on such things (about 85%) than the private nonprofit average (69%).

In contrast, online schools spend about 40% of what conventional schools spend on academic support and student services. Notably, the wages and benefits share of academic support and student services spend is much lower (30-40%), and broadly in line with the percentage at other schools.

So why are online schools spending “so much” on faculty?

Of course, online schools are spending a lot less in absolute terms, not encumbered by physical classrooms and lots of full-time faculty. Nevertheless, the fact that online schools’ faculty account for 85% of instructional spend reveals something about educational technology: support services are easier to automate than instruction.

At online schools, the majority of spend on academic support and student services is on technology, not people. At campus-based schools the same is true, but they spend on technology plus buildings and other in-person resources. But for instruction, most spend is on faculty, even at online schools.

Yes, support staff are paid less than faculty, but the disparity also highlights that online learning has not managed to dethrone the faculty. The typical asynchronous online class may, compared to a conventional one, reduce faculty time per student, and permit a faculty member to oversee a larger number of students in total. Such efficiencies account for much lower instructional spend per student at online schools.

It is hard, however, to point to mainstream improvements to this typical online instructional model—in place now for over 20 years. Adaptive learning companies have pushed a more automated experience but have yet to operate outside a few quantitative, lower division courses. Schools have found adaptive learning to be a useful component of instruction, not a replacement for faculty who must still take on the seemingly un-automatable job of real-time problem solving with individual students.

Indeed, that reality may explain why online schools invest relatively more in support staff. This is work only humans can do, but support staff cost less. Support technology, such as systems that alert when a student is behind schedule, have gained more traction than the likes of adaptive learning.

The Bottom Line

Based on the data analyzed here, online schools radically reduce instructional and support costs because they eschew expensive buildings, limit full-time faculty, invest in cheaper support staff, and employ asynchronous instruction that permits less faculty time per-student and greater economies of scale. But despite a model defined by technology, almost all instructional spend still goes to faculty. In relative terms, so far, online learning does not mean reduced spend on faculty.

This marks the limit of online learning, something that many companies—and some institutions—are working feverishly, and perhaps in vain, to overcome.

You may be entitled to a complimentary pass to Eduventures Summit. Send an email to summit@nrccua.org to inquire about eligibility.

Not a current client? Click here to register today to reserve your seat to higher education’s premier thought leadership event.