Will we look back on 2015 as the year when the market and policymakers got serious about alternative credentials?

We all know the backstory. Steady globalization and automation have eaten away at the economic status quo and driven U.S. higher education enrollment up 40% in the last 15 years, more than double population growth. Yet return on investment (ROI) is under unprecedented pressure. The U.S. is riding a “perfect storm” of ballooning student debt, lackluster graduation rates, and questionable graduate quality. Everyone seems to agree that more higher education is central to the national strategy, but it is also clear that the nation needs to rethink higher education if ROI is to pass muster.

One can question bits and pieces of the case. Sticker price may be soaring but net price, what students actually pay, is more modest and stable. The boom-and-bust of much of the for-profit school sector may mask underlying continuity. The wage premium that comes with a degree has never been higher, calming fears about student debt.

Still, it’s hard to feel good about these three data points:

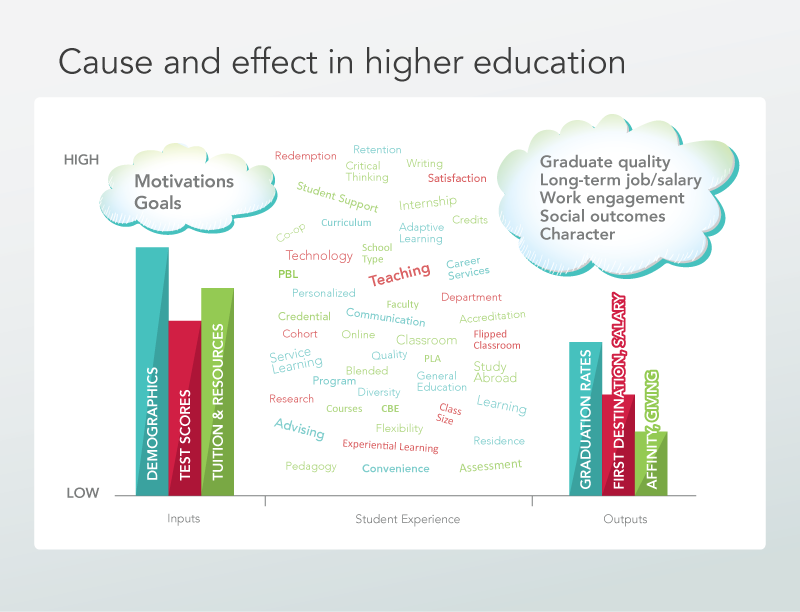

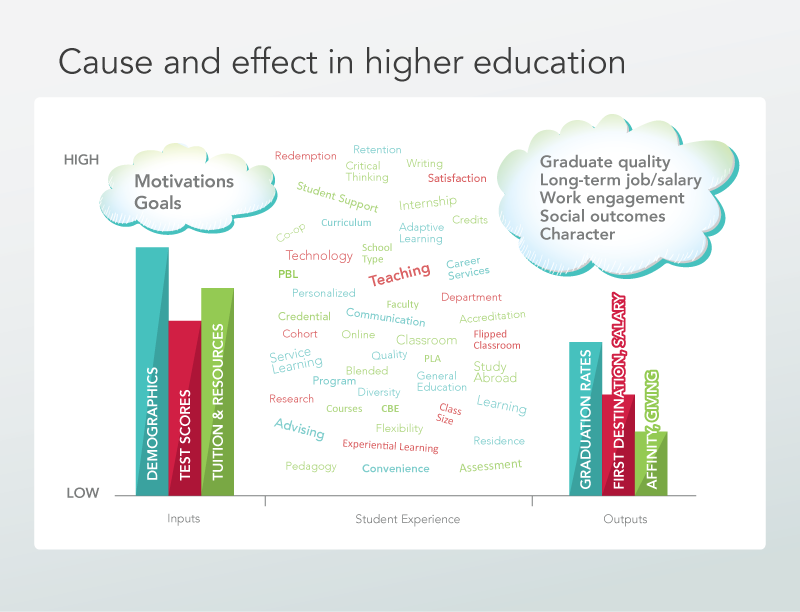

While inputs are reasonably well understood, outcomes are rudimentary. The student experience—what turns inputs into outcomes—is a glorious maze of academic autonomy and student choice. In 2016, watch for Eduventures’ new Student Experience Dashboard, our effort to make sense of this complexity and interrogate cause and effect more closely.

Where do alternative credentials fit in? Alternative credentials offer the potential to forge clearer student pathways to capability. In 2015, we saw two interesting developments.

While inputs are reasonably well understood, outcomes are rudimentary. The student experience—what turns inputs into outcomes—is a glorious maze of academic autonomy and student choice. In 2016, watch for Eduventures’ new Student Experience Dashboard, our effort to make sense of this complexity and interrogate cause and effect more closely.

Where do alternative credentials fit in? Alternative credentials offer the potential to forge clearer student pathways to capability. In 2015, we saw two interesting developments.

- Graduation Rates. According to the National Student Clearinghouse, the six-year undergraduate completion rate is a mere 55%—and it’s declining. Lest we forget, an associate degree is supposed to take two years to complete, and a bachelor’s degree should take four years. The fact that barely half of students complete anything in six years should ring alarm bells.

- Employability. In 2012, the OECD ran its first international survey of adult skills. Only 8-16% of U.S. adults achieved literacy, numeracy, and problem-solving proficiency at a level judged to be equivalent to a bachelor’s degree, yet 34% had such a degree. A sizeable gap was common in many countries. In the 21st century, higher education needs to achieve quality at scale, not trade one for the other.

- Premium. Yes, the degree wage premium is higher than ever, 95% for those with a bachelor’s degree and 136% for those with a master’s degree when compared to high school graduates. In constant dollars, though, the median wage for bachelor’s and master’s degrees has slowly eroded since the turn of the century. The fact that non-graduate wages have eroded faster does not alter the reality that degree ROI is not what it used to be.

While inputs are reasonably well understood, outcomes are rudimentary. The student experience—what turns inputs into outcomes—is a glorious maze of academic autonomy and student choice. In 2016, watch for Eduventures’ new Student Experience Dashboard, our effort to make sense of this complexity and interrogate cause and effect more closely.

Where do alternative credentials fit in? Alternative credentials offer the potential to forge clearer student pathways to capability. In 2015, we saw two interesting developments.

While inputs are reasonably well understood, outcomes are rudimentary. The student experience—what turns inputs into outcomes—is a glorious maze of academic autonomy and student choice. In 2016, watch for Eduventures’ new Student Experience Dashboard, our effort to make sense of this complexity and interrogate cause and effect more closely.

Where do alternative credentials fit in? Alternative credentials offer the potential to forge clearer student pathways to capability. In 2015, we saw two interesting developments.

Boot Camps

Forecasts indicate that coding boot camps’ revenue, enrollment, and graduates will have tripled in 2015 compared to 2014. There are now dozens of boot camps nationwide. Key players include Galvanize, General Assembly, and Dev Boot Camp. This year, major “old school” corporations also showed interest: Apollo Group snapped up Iron Yard, and Learning House acquired Software Guild. Even universities are joining in. In October, Northeastern University announced its own boot camp on data analytics, Level. Boot camps are a breath of fresh air. Conventional “innovation” in higher education tends to be characterized by online learning, convenience, and part-time study. The recent enthusiasm for competency-based learning has added self-paced learning and low cost programs to the mix. Boot camps are proudly inconvenient and expensive, stressing full-time, intensive study in a cohort-based, face-to-face format. They emphasize a goal of learning efficacy rather than a particular delivery mode or price point. Compared to a much more expensive and longer bachelor’s degree, students’ willingness to pay $20,000 for a four- to six-month boot camp with a tangible career outcome suggests that there is value in a bit of inflexibility. The big news in 2015 was the announcement of the federal “experimental site” program, which allows selected boot camps and other alternative providers to receive federal student aid in partnership with conventional universities and colleges. The application deadline just passed in mid-December, so we don’t yet know which organizations applied or who will be selected. If the “Distance Education Demonstration Program,” the 1999-2005 government trial that permitted wholly distance programs to receive federal aid, is any indication, the latest experiment may unleash a new wave of providers and enrollment.Teacher Preparation

The new Every Student Succeeds act (ESSA), which replaces the controversial No Child Left Behind, widens the door for alternative routes to teacher preparation. No Child Left Behind privileged conventional teacher preparation degrees, one cause for the boom in education-related master’s degrees over the past decade. ESSA levels the playing field, encouraging states to decide what role alternative routes and providers, such as Teach for America, should play and how to regulate them. Almost all states already sponsor some kind of alternative pathway. Many of these alternative routes sidestep a degree in favor of a concentrated training period followed by intense mentored practice. Other models, like the Relay Graduate School of Education, reconfigure a master’s degree on an apprenticeship model. Some universities offer their own alternative programs. The emphasis is on effectiveness of teacher preparation, not conventional approaches, and the line between student and employee is blurred. It’s worth noting that federal aid is not available to students in alternative teacher preparation (ATP) programs unless the provider is a conventional college or university. It’s quite possible that ATP programs will be among the applicants to the government’s “experimental site.”Ifs and Buts

Of course, neither boot camps nor ATP programs are proven or without their critics. Issues include:- So far, boot camps seem to attract bachelor’s graduates, not students looking for an alternative.

- Little is known, beyond company marketing, about boot camp graduates’ job placement rates, and it is too early to judge long-term impact.

- ATP programs are criticized for low teacher retention, such as after TFA’s two-year commitment.

- Studies of conventional and ATP programs tend to reach the bland conclusion that, in terms of quality, the two are much the same.