Online learning has been part of higher education for almost 30 years now. Students studying either fully or partially online make up 31% of U.S. undergraduate enrollment (as of fall 2016), and 37% of graduate enrollment.

But what does “online learning” really mean? The term masks a range of styles and features.

We are pleased to announce the publication of CHLOE 2: A Deeper Dive, an annual survey of online learning leaders. Short for Changing Landscape of Online Education, CHLOE is produced by Eduventures and Quality Matters and is supported by iDesign and ExtensionEngine.

From enrollment and competition, to organization and leadership, to tuition and outcomes, CHLOE seeks to understand online learning policies, practices, and plans, and, ultimately, institutional impact.

Read on for a preview of CHLOE 2, and a discussion of some interesting differences among online programs.

Allow us to introduce you to CHLOE

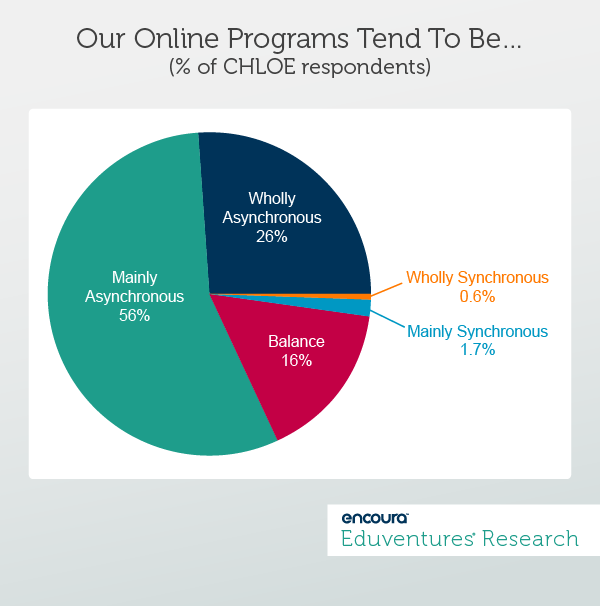

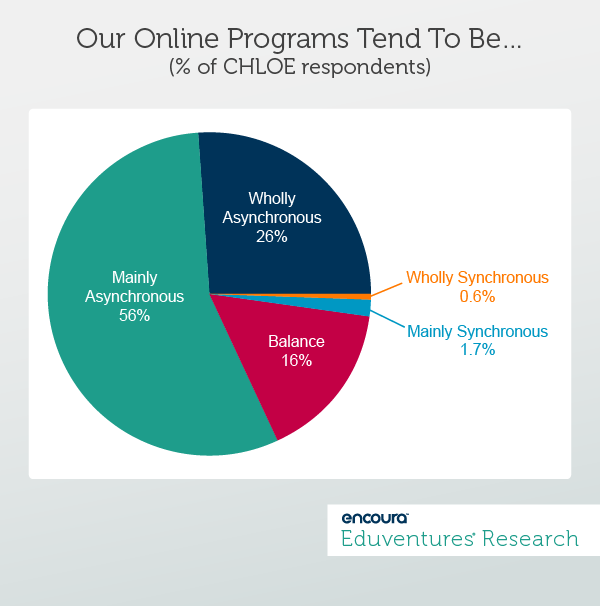

One objective of CHLOE 2 is to break online learning into different pedagogic dimensions. It is not an easy task. A basic distinction is synchronous versus asynchronous online learning (see Figure 1). As a reminder, synchronous learning means that students and faculty engage in class activities at the same time (e.g., a video conference), but do so at different times for asynchronous learning (e.g., threaded discussions). In our CHLOE 2 sample, 82% of respondents said their online programs are wholly or mainly asynchronous. While it was exceptional for a school to say synchronous is the dominant model, 16% of the sample indicated a balance between the two.

Figure 1.

The fact that 56% of schools describe their online programming as mainly rather than wholly asynchronous suggests that synchronous delivery plays a limited role in many programs. When asked why asynchronous or synchronous was dominant, online leaders on all sides cited student and faculty preference and perceived learning effectiveness. CHLOE 2 then looked for associations between type of online learning and perceived student interaction and personalization—two commonly noted facets of effective learning. Interaction helps connect and engage distance students, exposes an individual student’s ideas to wider scrutiny, and encourages breadth of communication. Greater personalization is said to better tailor learning to the needs and preferences of individuals, boosting engagement and potentially reducing time and cost. Revived interest in competency-based learning and the emergence of adaptive learning software are cases in point. Things like interaction and personalization are hard to measure directly at scale and are somewhat subjective. The CHLOE survey asked online leaders to offer their take on the relative interaction and personalization of their institution’s online programs. Subjective or not, the results are interesting. CHLOE 2 respondents can be divided into four groups:- Extensive interaction and personalization (13% of the sample)

- More interaction than personalization (45%)

- More personalization than interaction (4%)

- Limited interaction and personalization (37%)