Recent headlines about the continued fall in online enrollment post-pandemic obscure the fact that at the undergraduate level, fully online student headcount is considerably higher than the pre-COVID trend. Before the crisis, only 14% of undergraduates (excluding dual enrollment) were fully online. Post-crisis (fall 2022), the ratio jumped almost two-thirds to 23%.

Who are these new online students and which types of schools have sustained sizeable online enrollment?

Online Is (and Isn’t) Mainstreaming

To understand the fall 2022 online undergraduate data, both absolute growth and market share must be considered.

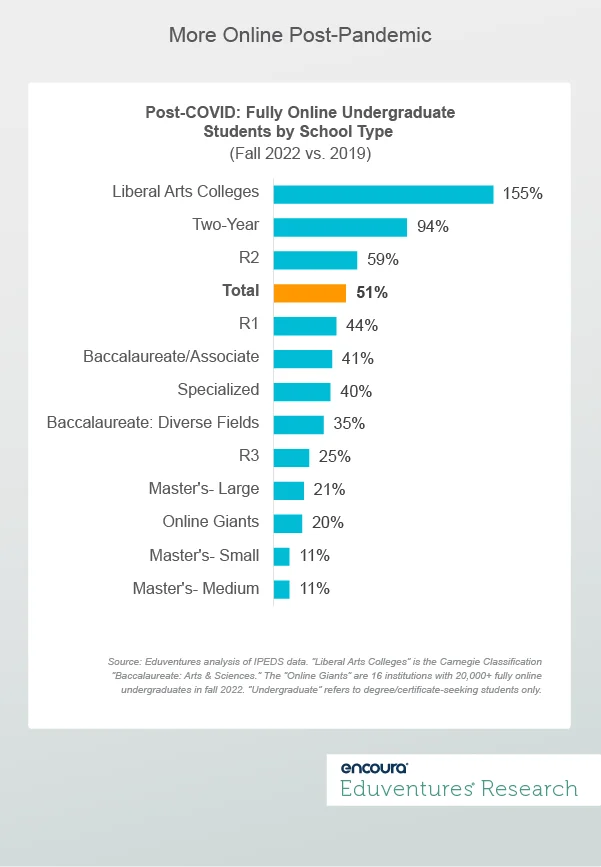

All types of institutions—two-year and four-year, public, private, for-profit—posted big online enrollment gains post-pandemic. Even schools that were not very active online pre-COVID saw momentum. For example, top research universities (R1s) grew fully online with undergraduate (degree/certificate-seeking) headcount of 44% versus 2019. Specialized schools leapt 40% and Liberal Arts colleges 155% (from a low base).

Figure 1 shows fully online undergraduate enrollment growth (fall 2022 vs. 2019) for 12 school types. (“Fully online” is used here to mean students enrolled 100% online—or close to it—at program level).

Figure 1.

Of course, the online enrollment baseline varies widely. In 2019, two-year schools had over 700,000 fully online undergraduates while Liberal Arts Colleges reported only 2,500. And online was more significant for some school types. Among two-year schools, fully online undergraduates accounted for a third of all undergraduates compared to 0.8% at Liberal Arts Colleges.

Yet—and this is important—because total fully online undergraduate (degree/certificate-seeking) headcount grew 51% over the period, most types of institutions actually LOST online market share.

Only two-year schools (29% share gain), Liberal Arts Colleges (70% share gain, but again, from a low base) and R2s (6% gain) improved online undergraduate share. All other school types lost share. This is true even for the Online Giants (16 schools with more than 20,000 fully online undergraduates as of fall 2022).

What this means is that today’s online undergraduate market looks LESS like higher education overall (in terms of enrollment distribution) than it did in fall 2019. The online undergraduate market has grown both MORE mainstream (because student numbers are up across the board) but also LESS mainstream because enrollment is more concentrated in certain school types.

The bulk of concentration happened among two-year schools, which went from having 35% share of the fully online undergraduate market pre-COVID to 45% in 2022. Before COVID, the two-year share of fully online and total undergraduates was almost identical. Now this sector’s online share is much higher than its overall share, which actually declined because total two-year school enrollment slumped (by 15%).

Enrollment challenges at two-years schools are clearly a driver of online programming, presenting enrollment as flexible and convenient for busy prospective students who doubt that they can accommodate conventional campus attendance. Indeed, this helps explain online undergraduate momentum generally: while online undergraduate enrollment grew net 51% between 2019 and 2022, total undergraduate enrollment fell by 7%.

The New Online Student?

But who are these new online students? The typical fully online undergraduate in years past was an adult learner, not a traditional-aged student. Is that changing?

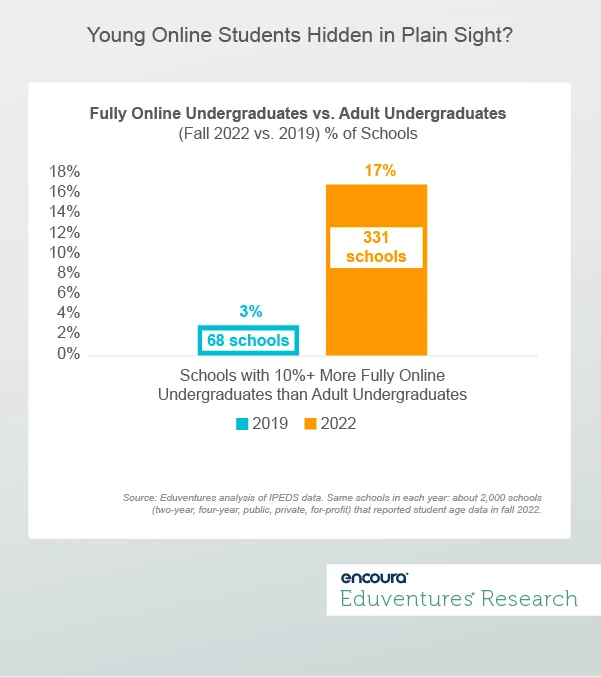

Online students are not reported by age in IPEDS, but Eduventures has a workaround. Figure 2 shows the change in the number of schools that report more fully online undergraduates than adult undergraduates. The implication is that at least the residual fully online undergraduates are of traditional age. There has been a big increase in the number of such schools.

Figure 2 uses a sample of some 2,000 institutions—of all types—that reported both undergraduate student age and modality in fall 2022 and 2019.

- Figure 2.

In 2019, based on this sample, only 3% of schools reported more (10%+) fully online undergraduates than total adult undergraduates (aged 25 and above). Another 4% of institutions were close to even (fewer than 10% to fewer than 10% less). Three years and one pandemic later, the ratios were 17% and 12%, respectively.

Among this sample, residual younger fully online undergraduates number some 300,000. Eduventures estimates that today there are some 700,000-800,000 fully online undergraduates enrolled nationally, aged under 25 (about 7% of the total in that age range)—at least double the pre-pandemic total. The majority are aged 22-24, blurring the line between traditional-aged and adult students.

What sort of schools enroll these students?

Not surprisingly, two-year schools are overrepresented, accounting for about half of schools with more fully online than adult undergraduates. But all 12 school types from Figure 1 are present in this cohort of institutions enrolling younger students in fully online programs.

This cohort is also geographically diverse, spanning 46 states. Holdover COVID campus closures into fall 2022 no doubt explains young fully online student scale at some institutions, but this is a primarily post-pandemic phenomenon.

Here are some examples from fall 2022:

- Sampson Community College: a two-year school in North Carolina with about 900 undergraduates. Some 550 study fully online but fewer than 350 are adult undergraduates.

- University of the Cumberlands: a private, four-year, doctoral-granting institution in Kentucky with about 4,600 undergraduates. Some 2,600 were reported as fully online alongside only 1,800 adult undergraduates.

- Unity College: a specialized, private, four-year, environment-focused institution in Maine, operating primarily online. The school reported about 3,500 fully online undergraduates, some 1,400 more than the school’s total adult undergraduate headcount.

- Florida State University: a public R1 with almost 32,000 undergraduates, including about 1,500 fully online; but the school enrolls fewer than 1,100 adult undergraduates.

Time will tell whether these and other apparent pockets of scaled younger undergraduate, fully online enrollment, continue to grow, and the extent to which such enrollment is driven by institutional strategy or pandemic happenstance.

The Bottom Line

The mist is beginning to clear in the post-pandemic aftermath. Another year of data is needed to be definitive, but it appears that COVID had a big net positive impact on undergraduate enrollment online. Schools of all shapes and sizes have posted big fully online enrollment gains; although the two-year momentum is such that the post-pandemic online undergraduate market is less balanced than previously.

The online market was getting crowded before COVID; now it is jam-packed. Institutional online strategy needs to transcend just “being online.”

As online risks running out of headroom in the already online-centric adult undergraduate and graduate markets, awakenings in the much larger traditional-aged undergraduate segment are welcome.

But it is unlikely that today’s version of online learning will prove a good fit for younger students. Programs that leverage the best of online and campus—helping institutions manage costs and enhance the student experience beyond just convenience—hold the most promise for the typical young undergraduate.

How online learning integrates into the traditional-aged undergraduate experience may prove the pandemic’s most enduring—and exciting—legacy for higher education.